The Architecture of Departure

At the end of Episode 24 of Cowboy Bebop, an animation series, Faye Valentine, one of the protagonists, runs toward her childhood home. After 54 years of a cryogenic freeze, she has woken up and has no memory of her past. Much to her dismay when she reaches the site of her home, she finds only rubble where a structure once stood decades ago. She goes into the place, sits on the ground where her childhood bedroom would have been, and draws a rectangle from memory. This act of drawing indicates the interplay between memory and loss. Faye has lost the physical remains of her home, but she still holds the shape and feelings associated with that place. Therefore, is something truly lost if it holds space in our memory? But more importantly, what do we do with the loss that we encounter in our lives?

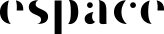

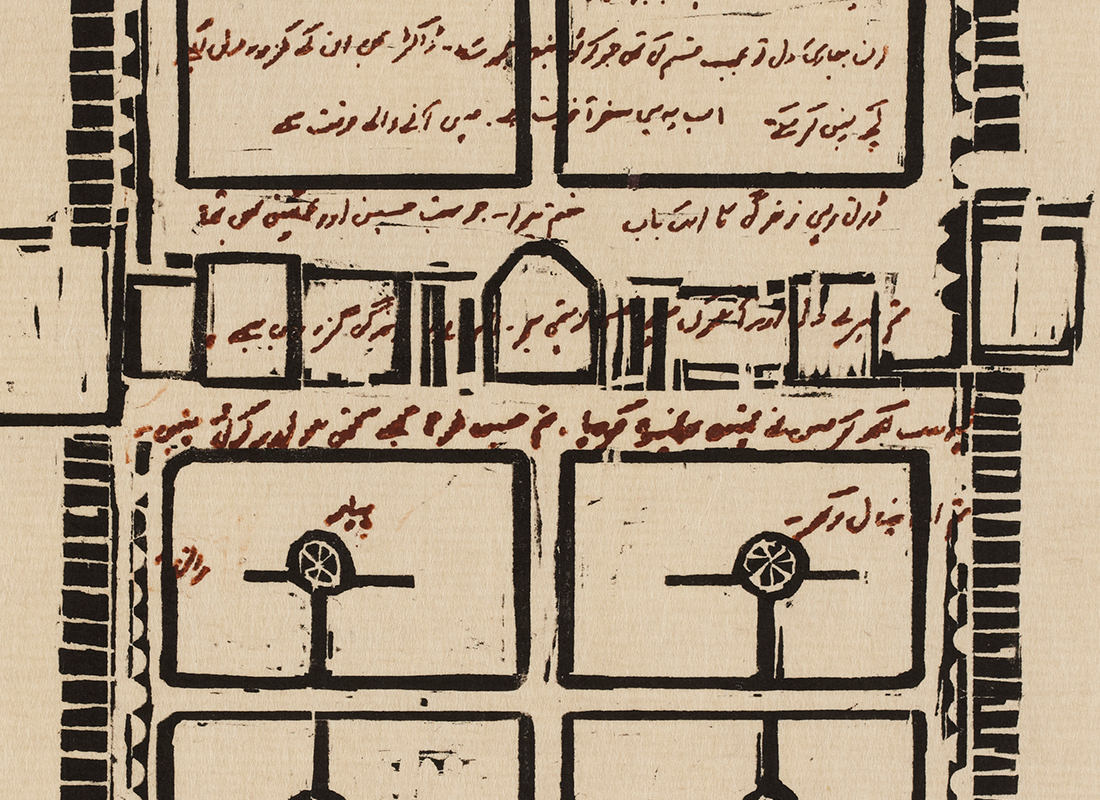

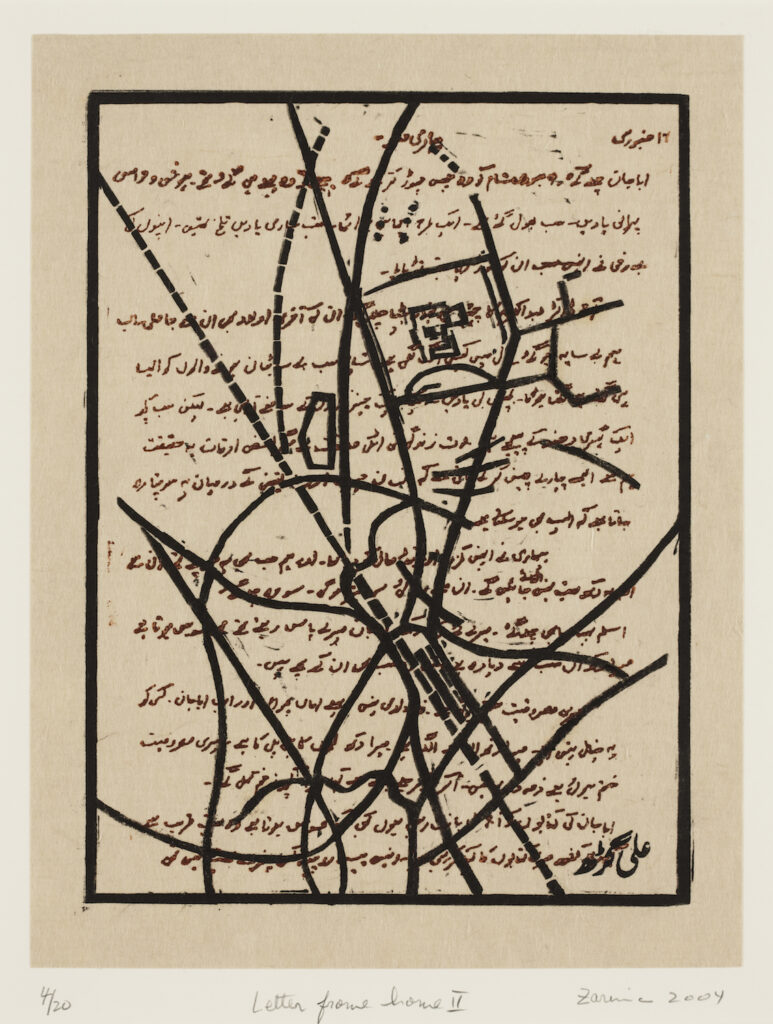

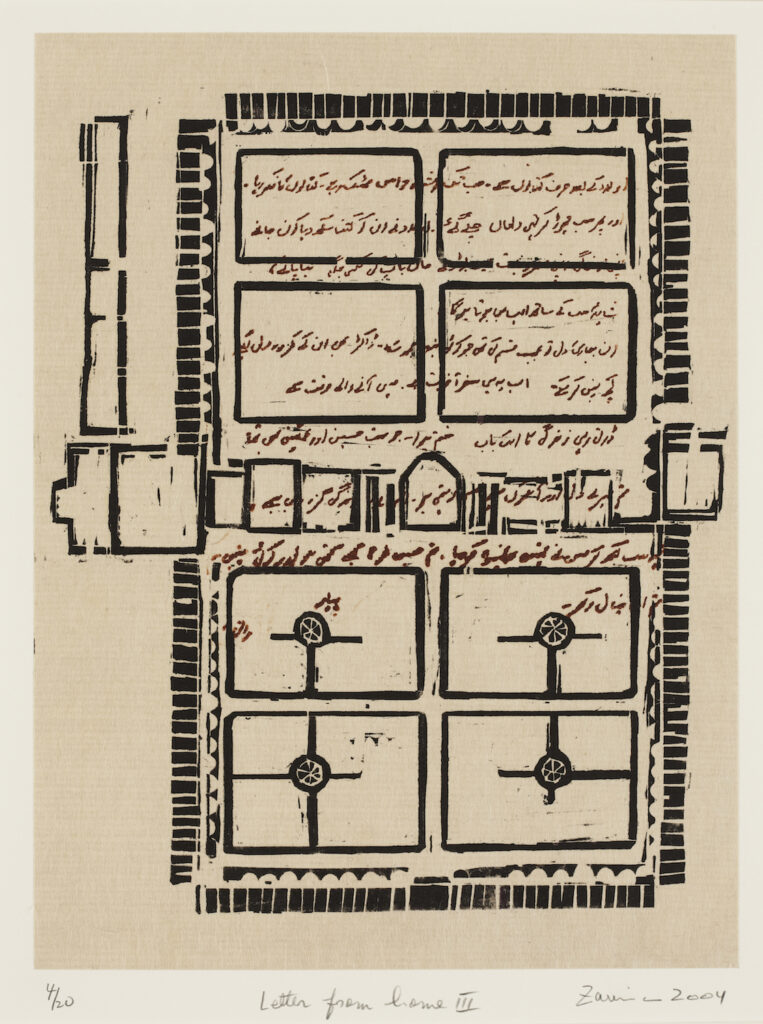

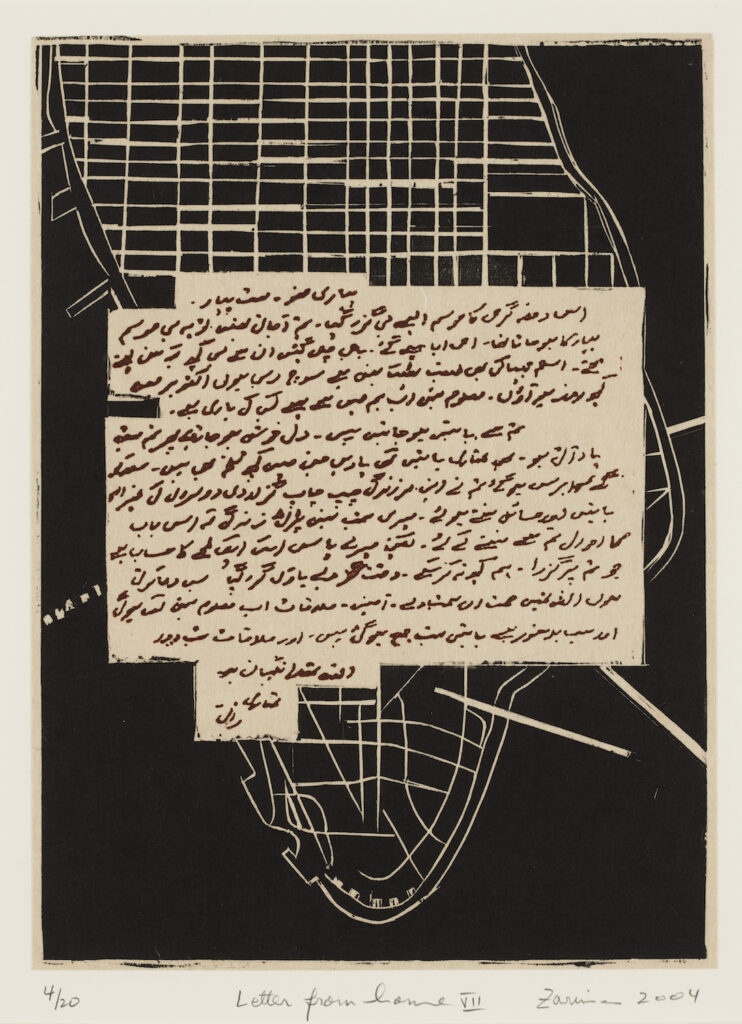

Aligarh-born artist Zarina (1937-2020), in her work Letters from Home (2004) and These Cities Blotted into the Wilderness (2003), presents this complex matter of memory and loss, seen in Faye’s narrative, as she examines themes of language, migration, geopolitics and meaning-making to show how art can help us negotiate rupture and departure to make sense of our multiplicities. Letters from Home, housed at Tate, is a display of eight monochromatic woodblock and metal-cut prints, showing the layouts of her homes on letters Zarina received from her older sister Rani. Rani was living in Karachi while Zarina moved to various cities due to her husband’s changing posts with the military. Rani, wanting to reach out to her sister, would write letters about their shared memories but never send them out. The letters were written in Urdu, the language of undivided India that show a combination of Persian, Sanskrit and Hindi dialects. Rani expresses how she misses Zarina and alludes to the shape of home after the advent of partition. The contents of the letters also include news about their mother’s passing, the ancestral house being sold, and their city, as Zarina knew it, now changing. The artist makes layouts of home and routes of the city as she recalls them from memory. Having lost her mother, other relatives, and the city as well, she displaces her laments onto the letters through the lines of black woodblock printing. Zarina’s etchings of her home give an image to the language, which might be indecipherable to a foreign audience but also shows us in both shape and feeling where Zarina’s home is, i.e., in the love of her sister’s words.

According to Bachelard, in Poetics of Space (1957), “[a] house that has been experienced is not an inert box. Inhabited space transcends geometrical space.”1 For Bachelard, the house is not a concrete entity, in fact, the house is very malleable in terms of its phenomenological becoming for those who experience it. In an interview with Tate about Letters from Home, Zarina recalls being asked about why she named the piece as such, to which she responds “But my sister is my home. We shared the same childhood. We lived under the same roof.”2 The letters evoke both a longing for the physical space of the past and allude to the space that relations, like sisterhood, create.

In The Architecture of Memory (1996), Joelle Bahloul says that “[as] such the search for time lost is also a search for space lost, a process that [Mikhaïl] Bakhtin was later to conceptualize in his notion of the “chronotope.”3 Here, the term chronotope refers to the interaction and visibility of time (chronos) and space (topos) in texts through language. Zarina’s work looks at time lost through the renderings of space in the form of floor plans and maps. The beauty of her work is its ability to make multiple histories visible, hers and the audiences simultaneously.

In her work, Zarina thinks about adding lived experiences to known history, like a varnish. To this end, her work is not limited to imagining the home she comes from. As the result of her husband’s moving for work, she has lived in many cities and created a new home in each place. Each time, she tried to (re)create the archetypal one, within the constraints of her new life. This, Zarina says in the Tate interview, “is the story of all immigrants.” 4 Immigrants must leave the places they have built their lives in, for different one. Her work often visits this swing between rupture and re-creation.

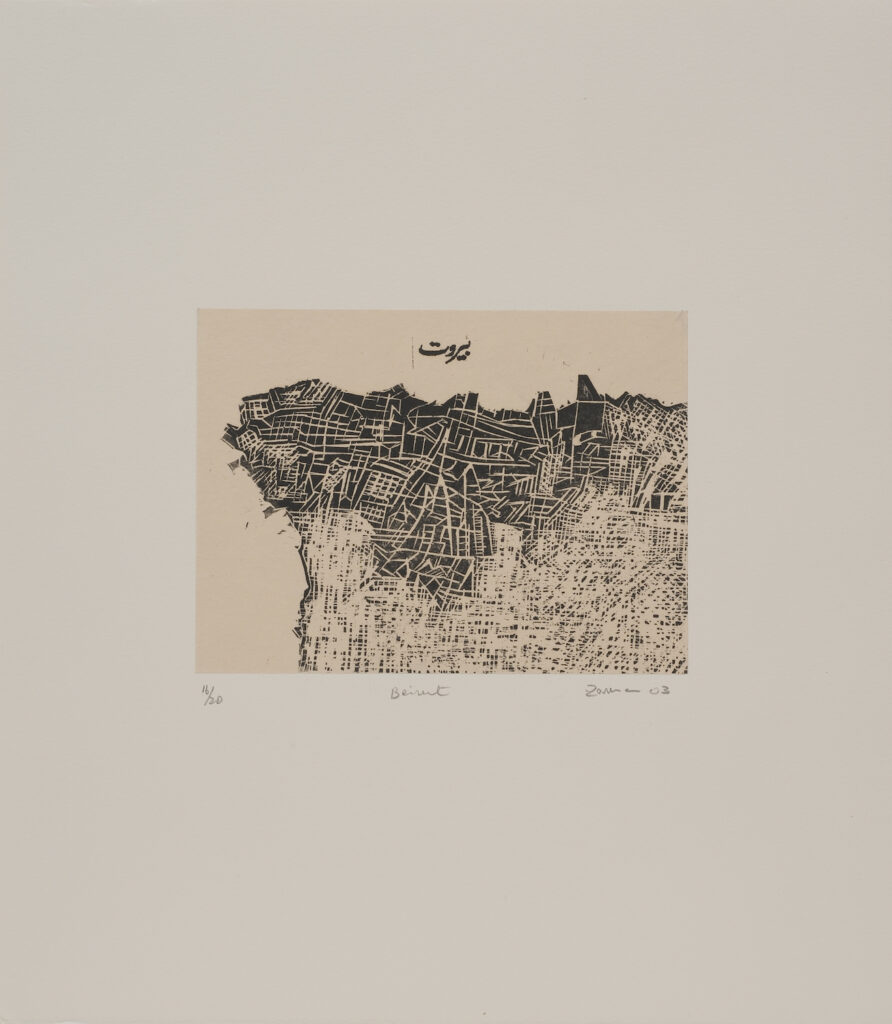

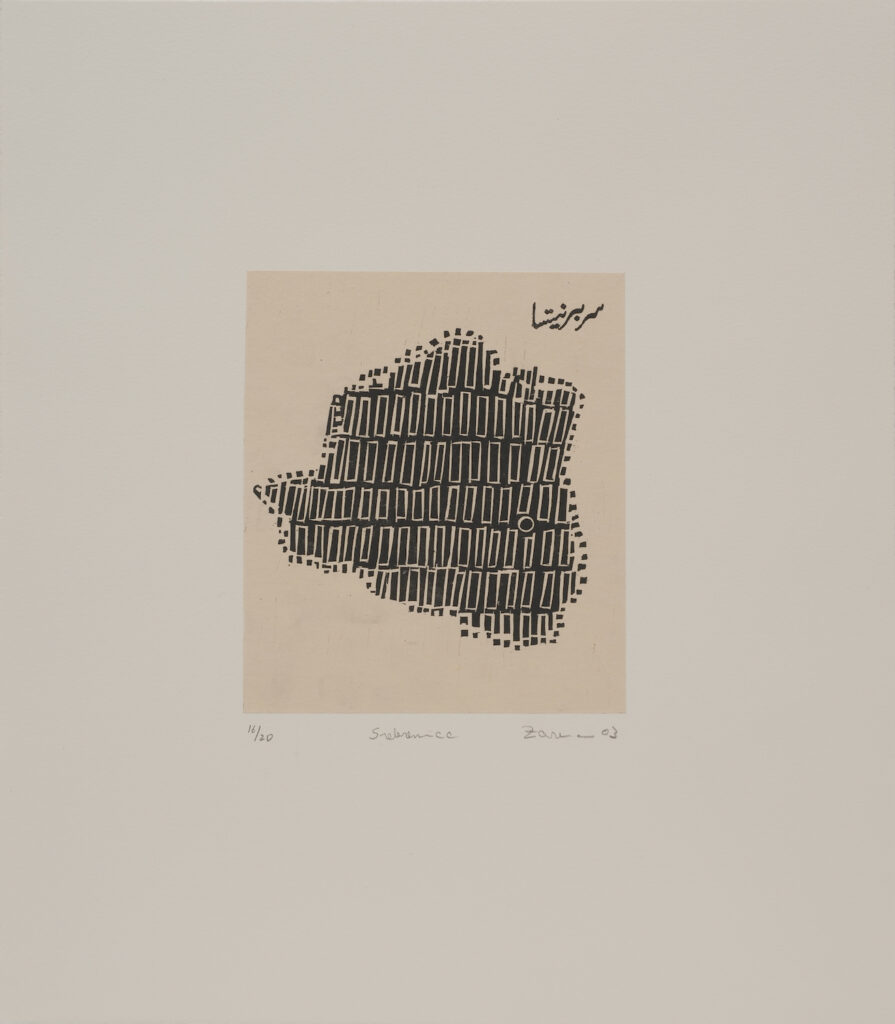

Zarina’s later pieces focus on the geopolitics of displacement and showcase the medium she is best known for—maps. In These Cities Blotted into the Wilderness, Zarina makes woodblock prints with Urdu text on Okawara paper, showing the maps of nine cities: Sarajevo, Beirut, Baghdad, Grozny, Srebrenica, Ahmedabad, Jenin, Kabul and New York. The artist as cartographer holds the shape of places before the history of violence and erasure has occurred. Zarina mentions in the catalog for the show that “[m]aps are sometimes all that remains of ancient cities.” Therefore, maps must speak of more than the violence that a place has endured.

In Letters from Home, Zarina, like an architect, sketches the land of her home through ridges of memory. But in The Cities series (2003), she becomes a historian, an archivist and a cartographer. She combines the map or the floor plan as a symbol of the material with the immateriality of distant memory and confessions. In her work, she asks viewers again and again how does one’s life relate to the world, how does one’s personal history intersect with political history, but most importantly she asks: what is the purpose of the truth that the cartographer might provide, as opposed to that of the artist?

Therefore, the artist asks us to find the cultural relevance of a map. What is a map for? What kind of function does it have in our lives? Zarina’s maps add another layer to their original purpose, which is to show direction. Instead, Zarina’s work shows us the unsettled nature of landscape and material. A map only provides an illusion of stability.

The artist understands this intimately as she mentions to Geeti Sen that the floor plans and the maps are interior realities, which “[she] can walk through again and again in [her] imagination.” 5 This positioning of maps within the imagination critiques the way in which colonizing forces have used maps as a means of conquest. Lines have been drawn with one stroke and separated cultures and families, such as Zarina’s. But Zarina’s artworks function differently from her colonizers. She is interested in documenting the rubble. She wants to record the past and not define a futurity, to account for the loss that maps don’t record, and worse, forget/eliminate. Without the desire for accuracy, she reveals their shifting nature, echoing the cartographer’s intention. Zarina makes maps, which are inherently violent in their propensity to demarcate boundaries, a space for reparative imagination. It is not just a space of conquest but a place for memories and stories. A space in which contradictions can be reconciled in some way.

But what are the issues for the viewer? In an interview with ART iT, Zarina says that “the predicament of the modern age is crossing borders to live in foreign lands and communicating through scraps of paper with quickly jotted notes.”6 We live in a time of arrivals and departures. Zarina’s work endeavours to give us a way of holding ourselves together in the chaos. She provides us with a structure of departure that looks like a feeling of longing, loss, pausing, seeing, witnessing and creating. The form can be woodblock printing, but it can also be letters, maps and floorplans. She provides us with all these possibilities for creatively understanding how rupture affects us and how we belong to the world after that rupture.

In the same episode of Cowboy Bebop, before Faye goes to see her old house, Ed, another child, asks Faye why she wants to leave the team to look for her home, which may have changed after 54 years. She says “[b]elonging is the very best thing there is.” I think Zarina would agree with that.

1 Bachelard, Poetics of Space, p. 47. Beacon Press. 1994.

2 Tate Shots, Zarina Hashmi – ‘My Work is About Writing’, 2013. [Online]: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jXJpbpvcMDU

3 Bahloul, The Architecture of Memory, p. 8. Cambridge University Press. 1996.

4 Tate Shots, Zarina Hashmi – ‘My Work is About Writing’, 2013. [Online]: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jXJpbpvcMDU

5 Hashmi, Zarina, and Geeti Sen. “The Atlas of My World.”India International Centre Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 3/4, 2003, p. 240–57.

6 https://www.art-it.asia/en/u/admin_ed_feature_e/FHt6zkTwqhKfNOJcUbuV/

Mayookh Barua, a Los Angeles-based writer from India, is currently a Ph.D. candidate at the University of South California. His work explores sexuality, art, mythology, education and family through a queer South-Asian voice. A 2023 Roots.Wounds.Words fellow, his work has appeared in Roxane Gay’s The Audacity, Litro Magazine, The Third Eye, Mezosfera Magazine and elsewhere.