Shadow of Clear Glass: Wyn Geleynse and Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle

In his Natural History (77 CE), Pliny the Elder, admiring the many varieties of coloured glass, notes that “the highest value is set upon glass that is entirely colourless and transparent, as nearly as possible resembling crystal, in fact.”1 Almost two millennia have passed, and a longing for transparent glass remains, becoming highly conceptualized: “[W]e imagine glass to be purely transparent,” writes curtain wall expert Robert Heintges, “we will it to be transparent; we imbue it with an imagined essence of transparency, even when this is not the physical or visual reality.”2

In modern architecture, which has played a part in fostering imagined transparency, clear glass is not always desirable. Paul Scheerbart envisages the state and future of building with “coloured glass” which he asserts “endures” more than bricks, “destroys hatred” and illuminates happiness.3 Clear glass can also be “irritating,” as Le Corbusier puts it, because its ability to fulfill “the pleasure in seeing the play of the sky, trees, or general views outside” conflicts with the “desire to be secluded from the outside and especially to have some privacy.”4 Chicago nephrologist Edith Farnsworth, a notable victim of this pellucid irritant, describes living in her glass house designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe as being like “a prowling animal” or “a sentinel on guard day and night.”5 Moreover, she adds:

I don’t keep a garbage can under my sink. . . . Because you can see the whole “kitchen” from the road on the way in here and the can would spoil the appearance of the whole house. So I hide it in the closet farther down from the sink. Mies talks about his “free space”: but his space is very fixed. I can’t even put a clothes hanger in my house without considering how it affects everything from the outside. Any arrangement of furniture becomes a major problem, because the house is transparent, like an X-ray.6

Mies’s modernist vitrine does not function for Farnsworth herself but instead forces her to serve as its ideal manifestation; indeed, “like an X-ray,” its compelling transparency reveals whether she maintains the magnificence of the house and, whenever she fails, immediately exposes her as a disappointing inhabitant. Elizabeth W. Garber, a poet and author, as well as an acupuncturist based in Maine, is well-versed in such controlling, masculine transparency due to her uncompromising architect father, Woodie Garber, whose glass house in Glendale, Ohio, designed in the mid 1960s, was devoted to demonstrating an ideal of modern living “filled with modern furniture, art, sculpture, overhead lights and huge speakers for the record player.”7 Elizabeth, who spent her teenage years living in this proudly modern glass house, recollects that it was:

designed for us but that we had no voice in. . . . it was too bright, too loud. Not cozy. No privacy. Sometimes I felt exposed by day, and felt self-conscious when the long glass walls became mirrors at night. . . . I felt a shadow over our life in the glass house, a kind of dark mirror we were caught in. . . . Our lives became over exposed and boundaries forbidden. . . . Our life imploded.8

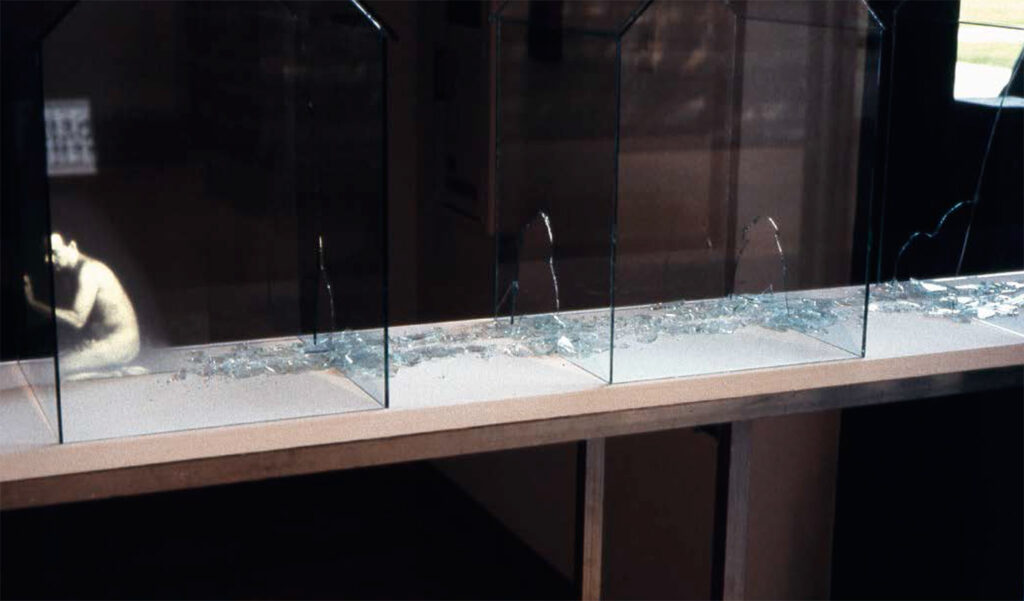

The vexing transparency of architectural glass underlies An Imaginary Situation with Truthful Behaviour (1988) by Canadian artist Wyn Geleynse, a sculptural projection that centers on the nightmare of a glass-enclosed life exposed to unlimited voyeurism. It consists of a sequence of plain glass houses, in one of which the image of a naked man is projected on a small glass screen. Kneeling against the wall, he never stops scratching it until breaking a hole through which to enter the next house; with a trail of tiny glass debris marking his passage, the man continues this process until he reaches the last glass wall, which cannot be broken down. The work was originally on view at the “On Track” exhibition at the 1988 Olympic Arts Festival in Calgary, when he looked to be in middle age. When the work was reprised in the artist’s 2006 exhibition at the Galerie Anton Weller in Paris, the naked man had aged in the past eighteen years, showing great contrast and paradoxically attesting to the enduring threat of the unchanged glass houses still imprisoning him.

Attacking the walls may suggest a war against the autocratic modernist sentiment shared by the male architects mentioned earlier; the naked man, subjected to this perverted spectacle, seems to be punished in recompense for the suffering Farnsworth or the young Elizabeth experienced. This punitive subversion repeatedly fails, however, as the indestructible final wall always states the perpetuity of confinement and subjugation, reiterating the futility of revolt through the inmate’s unrequited life. For Keir Keightley, a media theorist and contributor to the catalogue of Geleynse’s 2005 exhibition at Museum London in Ontario, this obstinate resilience can be associated with the nostalgia for “white, Western, masculine identity” as a backlash against a “‘feminization’ of the West” that diminishes male dignity, the crisis of which is alluded to by the predicament of the naked man exposed at all times to the curious gaze of others.9 In a sense, the unrealistic sturdiness of the glass represents a “dream of certainty” recurrent in “a world in flux and in flames,” in which, Keightley writes:

security and certainty walk hand in hand. People want to know that something, anything, is for sure, permanent, unchanging, indisputable. Gender becomes the foundation upon which this dream of certainty is built. And so a residual conception of masculinity – as the Othering and domination of women – returns with a vengeance.”10

The idea of everlasting glass imprisonment has already been targeted in Yevgeny Zamyatin’s pioneering dystopian novel We (1921), a story of failed revolution against the totalitarian One State constructed almost entirely of glass, in which all inhabitants are deprived of privacy and placed under control and surveillance. Protagonist and spacecraft engineer D-503 becomes attracted to I-330, a freewheeling dissident woman, and gets involved in her plot to take down the Green Wall that separates the One State from the outside world. The rebellion comes to naught as the Bureau of Guardians has detected the plot through a tip from U, the elderly female monitor who has a secret crush on D-503. The rebels, including I-330, are tortured and executed, while D-503 gets off with the removal of his imagination and returns to his original life with his renewed hope for the victory of reason against revolutions yet to come – that is, the triumph of transparency over opacity, clear mind over volatile emotion, masculine order over feminine chaos.

The distorted reality of utopian glass architecture in Zamyatin’s We materializes in Gravity Is a Force to be Reckoned With (2009) by Madrid-born Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle, an almost half-scale realization of Mies’s uncompleted project House with Four Columns (1951).11 In the work, this glass house is not only reduced in size, but also inverted. The original floor becomes the ceiling, and all interior elements and furniture are installed upside down; the exception is a cup and saucer shattered on the ground; however, its spilled contents seem to have remained on a coffee table suspended from above. People do not enter but look around the house from the outside, from all directions, as if assuming a role of surveillance and of monitoring an empty life in a glass box under the perpetual pressure of gravity. The house is no longer an ideal dwelling, having the benefit of sufficient illumination or seamless unity with nature. Rather, it is a sealed chamber refusing access to its interior and continually subjected to surveillance and the controlling gazes of others, where one is trapped, or only able to escape by breaking the glass wall.

Gravity Is a Force to be Reckoned With was presented in Manglano-Ovalle’s 2009 exhibition at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, in which was also included his 2006 Always After (The Glass House), an approximately ten-minute video work that focuses, in a continuous loop, on the movement and shimmering sound of massive glass debris being swept by a broom. The shards come from the windows smashed in May 2005 at “the ceremonial kickoff” of the façade renovations of the Illinois Institute of Technology’s S. R. Crown Hall designed by Mies, though almost nothing about this event is revealed in the video.12 The loop of Always After unfolds as a narrative with no beginning or end, confining us to “another site of anticipation” as curator Denise Markonish puts it in describing Gravity Is a Force to be Reckoned With.13 She writes:

The windows will be broken; the next revolution will start again, and for one moment, transparency, just like the utopias of Modernism, will tumble. But we are always left to wonder if the gesture is complete, if it will ever be complete.14

Geleynse and Manglano-Ovalle’s works delineate the paradoxical reality of glass architecture that combines visual openness and physical confinement, interlacing a utopian vision of society with a dystopian space of surveillance, which dominates the world of Zamyatin’s We. In their approach to transparent glass, permanence is emphasized rather than transience, robustness rather than fragility, qualities that resonate with the potential recurrence of ideological modernist beliefs, and the protests against them. As feared by the residents of the masterpiece glass houses and by Zamyatin’s I-330, transparency becomes violent particularly when it encases where our life takes place, but their cautionary tales contrast well with the unflagging construction of new glass complexes and office buildings. We wish glass to be transparent; we will keep wishing it. The shadow of clear glass resides in the persistence of our desire for transparency, while attending to its presence is perhaps as difficult as letting our eyes dwell on a window surface destined to be overlooked for the sake of what lies behind the pane.

1. Pliny the Elder, Natural History, vol. 6, trans. John Bostock and Henry T. Riley (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1857), bk. XXXVI, chap. 67, 382.

2. Robert Heintges, “Demands on Glass Beyond Pure Transparency,” in Engineered Transparency: The Technical, Visual, and Spatial Effects of Glass, ed. Michael Bell and Jeannie Kim (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009), 65.

3. A series of rhyming couplets written by Scheerbart, translated and quoted by Dennis Sharp in his introduction to Paul Scheerbart, Glass Architecture (1914), ed. Dennis Sharp, trans. James Palmes (New York: Praeger, 1972), 41.

4. Le Corbusier, “Glass, The Fundamental Material of Modern Architecture” (1935), trans. Paul Stirton, annot. Tim Benton, West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture 19:2 (Fall-Winter 2012): 298.

5. Edith Farnsworth, quoted in Nora Wendl, “Uncompromising Reasons for Going West: A Story of Sex and Real Estate, Reconsidered,” Thresholds 43 (April 2015): 23.

6. Ibid.

7. Elizabeth W. Garber, “Growing Up in a Glass House: An Architect’s Daughter Explores Modernism’s Shadow,” interview by Baron Wormser, Common Edge, April 11, 2018. [On-line]: https://commonedge.org/an-architects-daughter-explores-modernisms-shadow/

8. Ibid.

9. Keir Keightley, “Loopy Masculinity,” in Wyn Geleynse: A Man Trying to Explain Pictures (London, ON: Museum London, 2006), 20-21.

10. Ibid., 21.

11. For the link between Manglano-Ovalle’s Gravity Is a Force to be Reckoned With and Zamyatin’s We, see Denise Markonish, “You Say You Want a (Infinite) Revolution,” in Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle: Gravity Is a Force to be Reckoned With, online brochure of the artist’s 2009 exhibition of the same title. [On-line]: http://massmoca.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/inigo_brochure.pdf; Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle and Alex Rauch, “Interview with Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle Part I,” PORT: portlandart.net, February 27, 2010. [On-Line]: http://www.portlandart.net/archives/2010/0 /interview_with_6.html

12. Beth Wittbrodt, “A Smashing Success,” Illinois Tech Magazine (Summer 2005). [On-Line]: http://www.iit.edu/magazine/summer_2005/cover.shtml

13. Markonish, “(Infinite) Revolution.”

14. Ibid.

Taisuke Edamura is an art historian teaching at J. F. Oberlin University (Tokyo, Japan), specializing in contemporary art and criticism, with particular interests in (broken) glass in art and architecture. He received his M.A. in Art History from McGill University in 2008, and his Ph.D. in Art History and Theory from the University of Essex in 2014. His work has been presented at a wide range of international conferences and symposia, including Association for Art History (AAH) Annual Conferences and World Congresses of Comité International d’Histoire de I’Art (CIHA), and published in journals such as Invisible Culture, Kunstgeschichte, Modern Art Asia, Shift, and Wreck.