Neurodiversity: Recognizing difference

In the late 1990s, psychologist and sociologist Judy Singer1 developed the notion of neurodiversity, which was associated first with autism and advocacy for the rights of people with autism, then expanded to other types of neurodivergence such as ADHD, learning disabilities (dyslexia, dyscalculia, dyspraxia, dysphasia), giftedness, hypersensitivity, synesthesia, intellectual disability and so on. Yet the literature on this subject tells us that the word neurodiversity also refers to the whole range of human cognitive profiles. Therefore, it is identified not only with people who have been diagnosed as neuroatypical but also with all neurocognitive variations of the human species. As Juliette Speranza reminds us, neurodiversity is comparable to the biodiversity associated with the variety of life forms on Earth.2 Although this comparison to all life forms and ecosystems can seem useful to our understanding of the plurality of different cognitive profiles, we should not forget, as Singer tells us, that neurodiversity is not a natural phenomenon on the decline as biodiversity has turned out to be; on the contrary, it is connected to a cultural movement that advocates for difference and the recognition of difference.

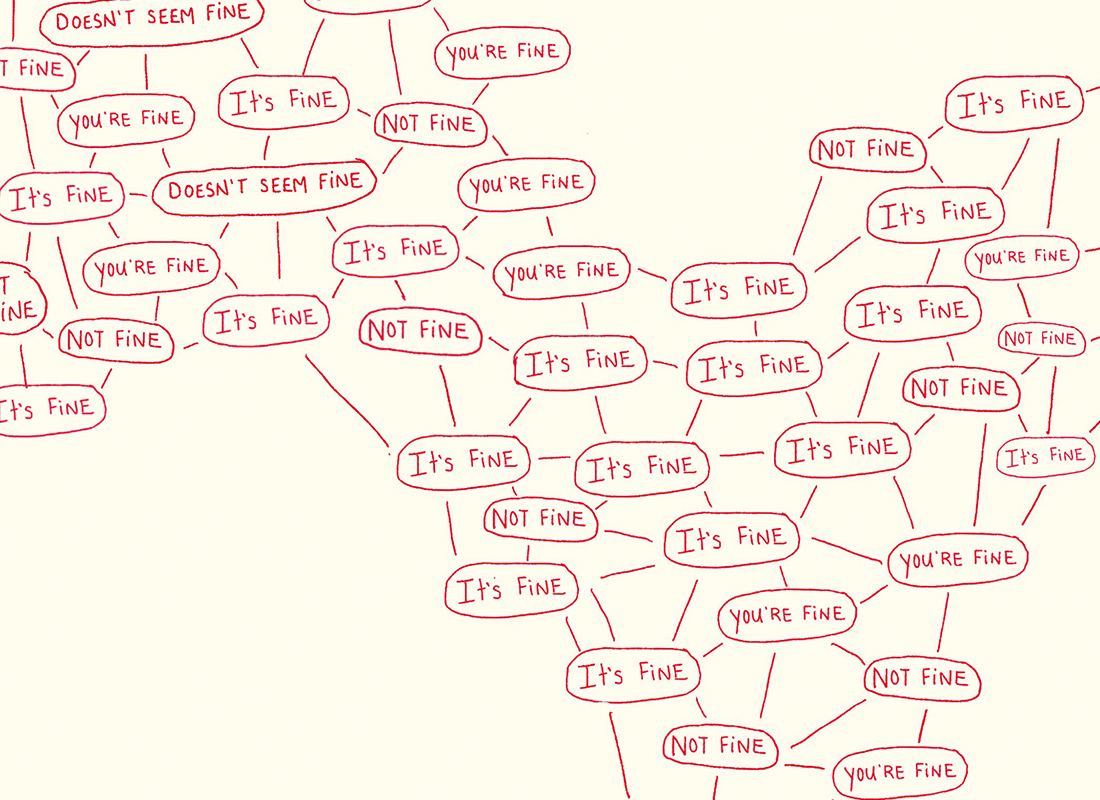

As a movement, neurodiversity obviously presupposes the neurocognitive plurality of human beings, yet it is defined first and foremost by a commitment to favour better inclusion of behavioural attitudes that are not neuronormative. Understandably, inappropriate reactions to people who lack the ability to function according to societal norms are frequent. Functioning differently from the dominant norm is often judged as a deficiency, leading to neuro-exclusion. This inevitably results in discrimination, which philosopher Amandine Catala calls “epistemic injustice” and which is characterized by the refusal to value the experience of neurodivergent individuals as being able to generate knowledge.3 In this case, people with “minoritized minds” are undeniably marginalized, misunderstood and condemned to their mental universe that is unfit to react normally to society. Given this injustice, which is based on prejudice and misunderstanding, the neurodiversity movement calls for a change in attitude regarding neuroatypical people, whether at school, at work or in life in general. Of course, the norm will always remain the norm, but it should be able to embrace other ways of thinking, reasoning and reacting to the surrounding world as much as possible. By including different modes of existence, neurodiversity allows us to envisage diverse forms of intelligence in which the need to create often seems to express itself. Yet to do this, it cannot be a question of imposing a particular mode of existence; on the contrary, “what should be protected is the relationship between modes of existence.”4

Art therapist Mélissa Sokoloff co-edited the articles in the “Neurodiversity” feature section, which is presented in two forms. In one part, a number of essays focus on the contribution of certain organizations involved in developing the autonomy of neurodivergent people, particularly through art therapy. In the other, there are articles relating the experiences of art therapists and autistic artists through interviews and commentaries. To this end, Sokoloff presents a conversation with Joelle Coriolan on the importance of artistic expression in art therapy. The practice of drawing has allowed Coriolan to establish a creative space in which her atypical identity is expressed. Hélène Arsenault and Rachel Chainey’s contribution focuses on Art Hives, an organization that considers the creative potential of all people. Their essay informs us about the underlying principles of this organization, which is based essentially on valuing inclusion. The creative activities that Art Hives offer encourage participatory practices based on dialogue and listening in an effort to create a sense of community.

Other organizations, such as Creative Growth in the United States or Hart Club and Project Art Works in Great Britain, accompany people with autism, helping them to develop their interest in the visual arts under the best possible conditions. In her essay, Cristina Moraru discusses how these organizations set up an environment for their members that encourages sharing, studio visits and exhibitions that reinforce the need for a fulfilled social life. Due to their support, each artist feels that they belong to an environment conducive to their desire to create. Moreover, these organizations believe that the art milieu benefits from becoming more inclusive. Based on the collective Project Art Works, shortlisted for the prestigious Turner Prize in 2021 and recently invited to documenta 15 (Kassel), this aspect seems to bear fruit. The Swiss organization Mir’arts has essentially the same mandate to promote artists with disabilities. In her essay, Teresa Maranzano, in charge of the Mir’arts program, focuses on the work of three artists, two of whom this association supports. Through her analysis, she demonstrates how artistic expression can increase awareness of one’s surroundings as long as it is done “in a stimulating and caring environment.”

The other texts in this section give voice to artists who openly show their cognitive specificity, hoping to break down the taboos that still exist around neurodiversity. Illustrator and photographer Émilie Léger spoke with Véronique Lagrange who, in her text, evokes the importance of the environment in the artist’s development and the pleasure she derives from living in surroundings vital to her stability. In an interview with Manel Benchabane, artist Célia Beauchesne mainly discusses her attraction to manual work, particularly her interest in drawing. For her, craftsmanship and repetitive work seem to be closely tied to the circumstances of those with autism. As with Beauchesne’s interview, Aseman Sabet’s conversation with artist Laurence Pilon highlights her development and the challenges she encounters as a neuroatypical artist. This interview also sheds light on the situation of artists in art contexts that are poorly adapted to the needs of people with autism, whether these are the funding bodies, galleries or even artist-run centres. In the “Essay” section, the artist Map offers a critical manifesto on “Western medical authority” in relation to autism. Map also discusses their personal development as a queer, non-binary artist, which has led to chronic fatigue due to the many challenges that a person with autism must overcome if they wish to become part of the visual art world. Moreover, as institutional inclusion in relation to diversity is far from being achieved and until the slogan “nothing about us without us” can become a reality, Map explains that to be left to “be and make in peace,” they chose to found an artist-run centre called DC-Art Indisciplinaire.

In parallel with the feature section, we are publishing, in the “Events” section, Jean-Michel Quirion’s text on the Biennale nationale de sculpture contemporaine (Trois-Rivières) and Pierre Arese’s text on documenta 15 (Kassel). In addition, this issue’s “Reviews” section includes nine accounts of recent exhibitions in Québec, Canada and Europe. Lastly, ESPACE continues to introduces recent works that have captured our attention in the “Books/Selected Titles” section.

Translated by Oana Avasilichioaei