Justine Skahan, De l’intérieur vers l’extérieur

Montréal

November 4 – 26, 2022

Although hundreds of years old, the tendency to associate a career in art with a life spent in poverty struggle is still common enough, and the past decade has seen a new and more developed focus upon the troubled place in which artists and economics meet. Usually this discourse is carried out in economic terms—neoliberalism, precarious employment, and all that—but it is natural for it to happen in the art milieu as well. Such an instance is De l’intérieur vers l’extérieur (From Interior toward Exterior), Montréal artist Justine Skahan’s latest exhibition, at Galerie McClure. Consisting of thirteen drawings and six paintings, Skahan presents her investigations of the artist’s situation the midst of today’s real estate investment bubble. The resulting exhibition, understated but incisive, does not present a particularly rosy outlook.

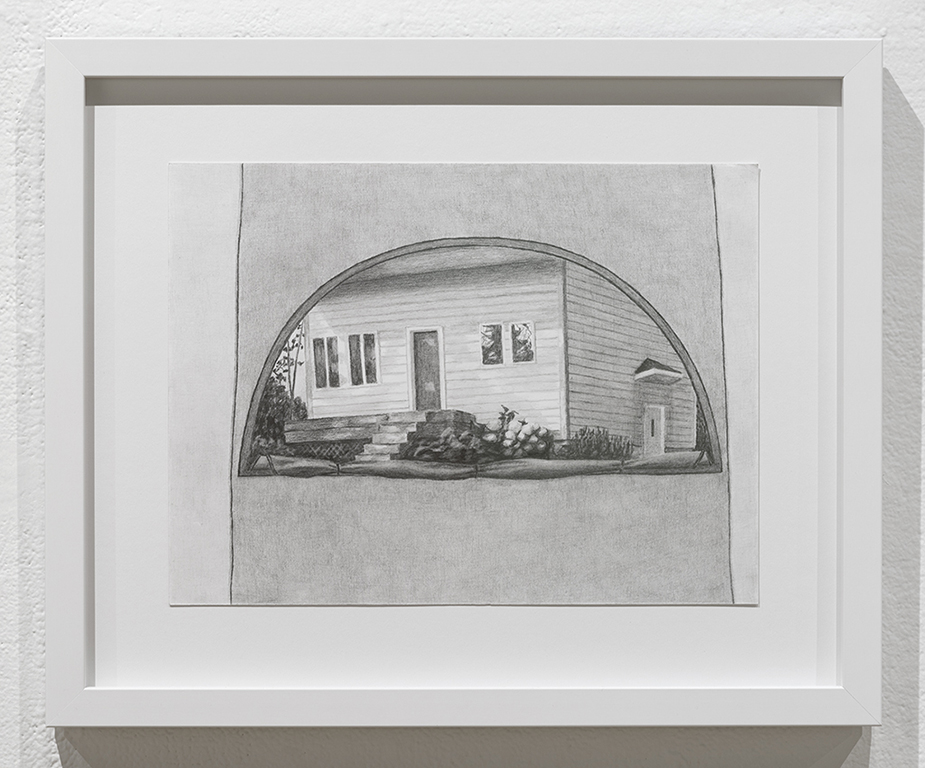

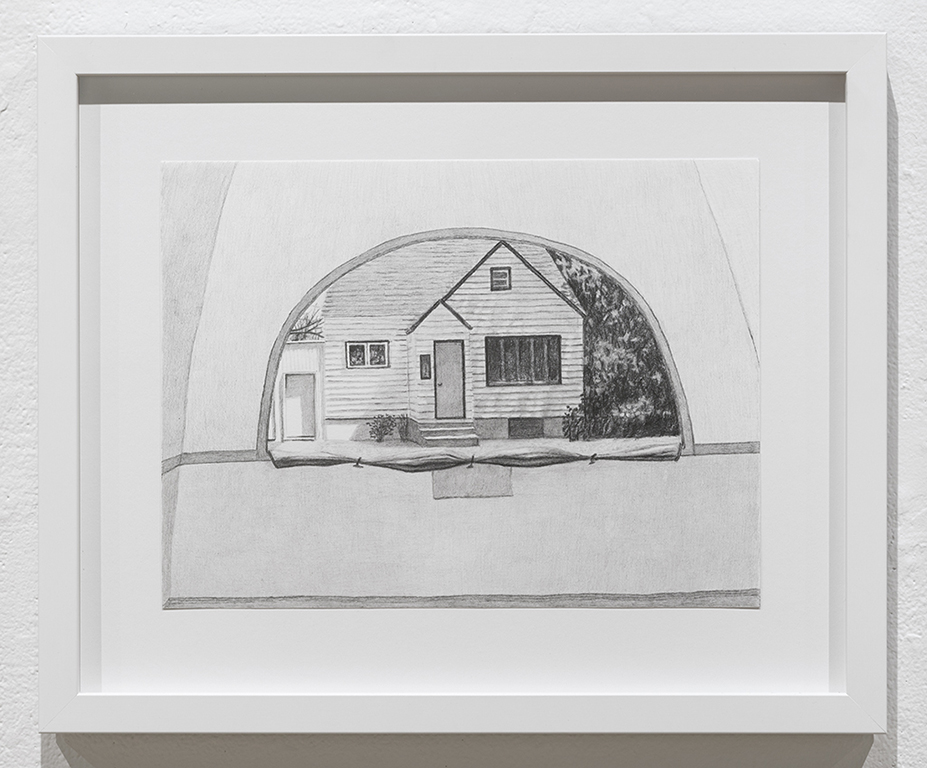

Skahan’s series of pencil drawings, titled Impermanent Dwelling (2021–2022), depicts modest houses, sourced from websites of real estate companies such as DuProprio and Centris, as seen by an unnamed viewer through the arched entrance of a tent. Most of the actual houses are in semi-rural locations within a couple of hours from Montréal. The artist told me that she selected houses in places where she thought she might be able to afford them, an hour or two from Montréal, but certainly not in the city—sorry, out of reach! But as Skahan browsed the real estate pages, she realized she couldn’t afford those either.

By implication, the artist positions herself as a denizen of the tent; as viewers, we imagine ourselves in the same place. The tent stands in for psychological states of insecurity and anxiety—perhaps all the more poignant for the fact that Skahan created most of the series while Montréal was under an 8 p.m. curfew (an anti-pandemic measure unpopular even among those who admitted its necessity). The tent’s key feature—the half-moon-shaped portal flap—offers several clues to the emotional state of the occupant. Sometimes it hangs clear and open. In one image, it is closed entirely—perhaps the occupant cannot bring herself to confront, again, the daily illusions and disenchantments. At other times, the flap is rolled up fastidiously and neatly secured with ties—a good day!

The houses vary as well. In some drawings, the house is rendered in clear detail while in others, through Skahan’s artful applications of an eraser, it is faded and indistinct. The tent denizen’s focus upon a futile goal—that American Dream, to which we up here in the north also feel entitled—seems to shift from drawing to drawing, as the houses fade in and out, a manifestation, perhaps, of the elusive possibility of owning one.

Shelters such as houses, tents and improvised dwellings—and, in particular, how they stand in for human psychological states and relationships—have formed a mainstay of Skahan’s work since art school. It seems natural that housing would emerge as a theme in art, given widespread concern over the past decade regarding the out-of-control housing market, especially as massive government transfers of wealth to rich people and their businesses has inflated asset prices—such as housing—even further, and put buying a house out of range for many.

Against this backdrop, simply leading a humble little life in a humble little apartment has become quite difficult. The casualties of this neoliberal dystopia pile up: ever-larger tent cities can now be found in most major centres, including Montréal, as higher property taxes––the consequence of higher property values––dazzle civic governments that do little or nothing to defend citizens against spiralling prices and rents. The parasites, it seems, are gradually killing the host.

This past May and June, to research these themes further for future projects, Skahan took part in a residency offered jointly by the artist-run centres AdMare, in the Magdalen Islands, and Occurrence, in Montréal. She spent much of the residency away from Montréal, both in the Islands and on the road, visiting a string of towns in rural Québec—Saint-Jean-Port-Joli, Ham-Nord, Val-des-Source, Thetford Mines and others—at each stop, seeking out potential dream homes.

As she discovered, the crisis in the real estate market is not strictly a big-city problem. While at AdMare, Skahan learned that the Magdalen Islands, too, were experiencing a crisis, one with its own perverse peculiarities. Outside buyers seeking summer homes have supercharged the market and driven up prices while the summer tourist economy squeezes renters. Some apartment dwellers are known to move into tents (a theme to which Skahan keeps returning) for the summer months, while renting out their apartments to eager, affluent tourists.

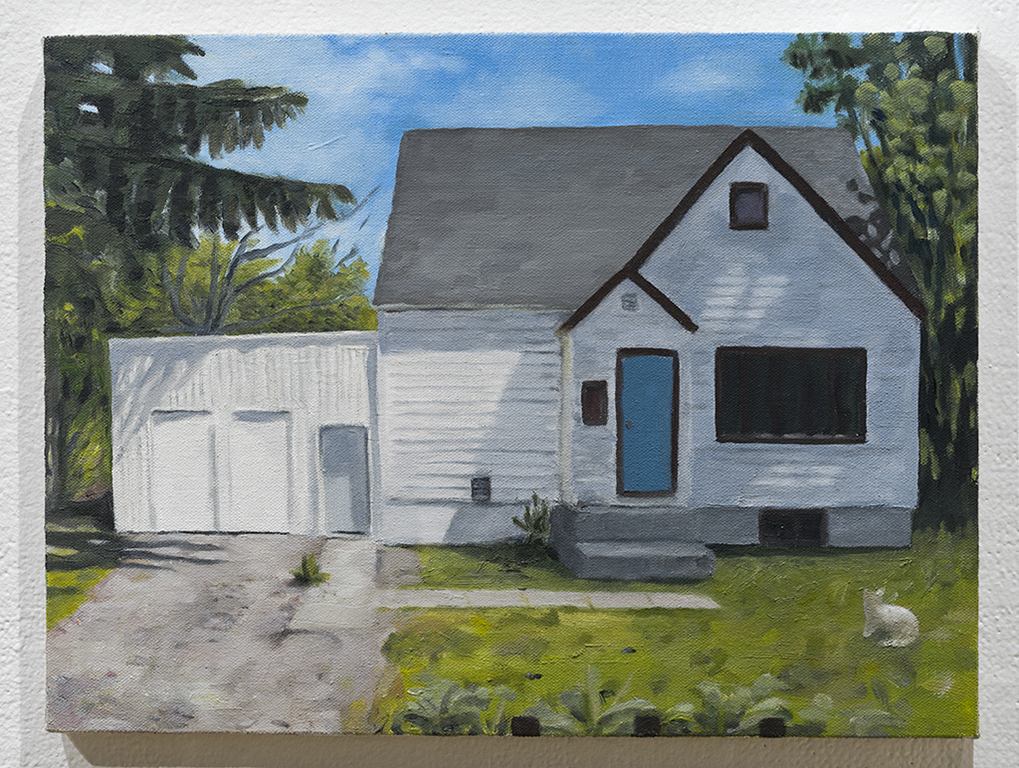

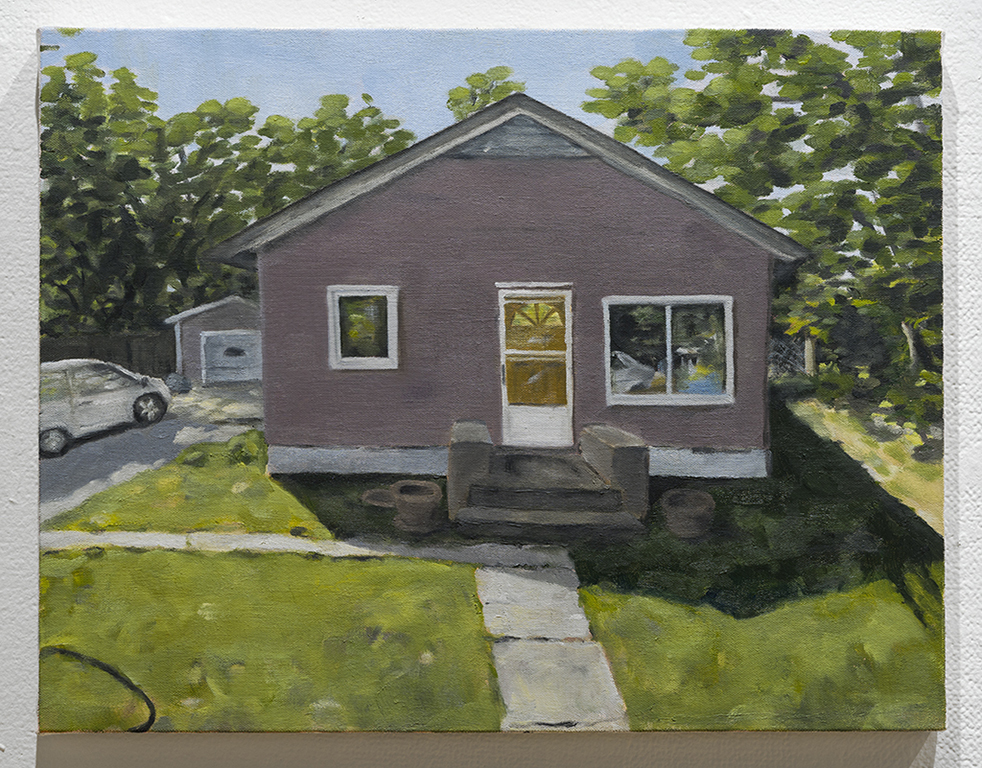

Skahan’s oil paintings feature a series (2021–2022) depicting four humble houses in rural or small-town Saskatchewan, generally in a more affordable $20,000–35,000 range. Like the drawings, these too are based on images selected from real estate websites; however, in Skahan’s drawings, the houses remain safely in the realm of real estate, whereas in the paintings, they venture a little beyond that. These houses are even more modest than those in the drawings; unlike the latter, here the idiosyncrasies of rural poverty are foregrounded: a drab blue front door, prefab tiled sidewalks that terminate in impractical ways, yards with odd decorative rock arrangements. One domicile is little more than a pink shack. The effect of such detail invites us to consider the interior life of these places; however, as in the drawings, Skahan’s paintings contain no people or signs of life, the exception being a solitary white cat patrolling a yard.

One of these paintings is titled One of the only houses in this country that I can afford (2021); however, the counterpoint to this sort of take-what-you-can optimism is that being able to afford something isn’t the same as being able to have it. To leave it all behind, along with everyone you know, in pursuit of a dubious fantasy of rural life on the prairie is, for most of us, an improbable trade-off—not to mention a possibly marginal, woebegone existence.

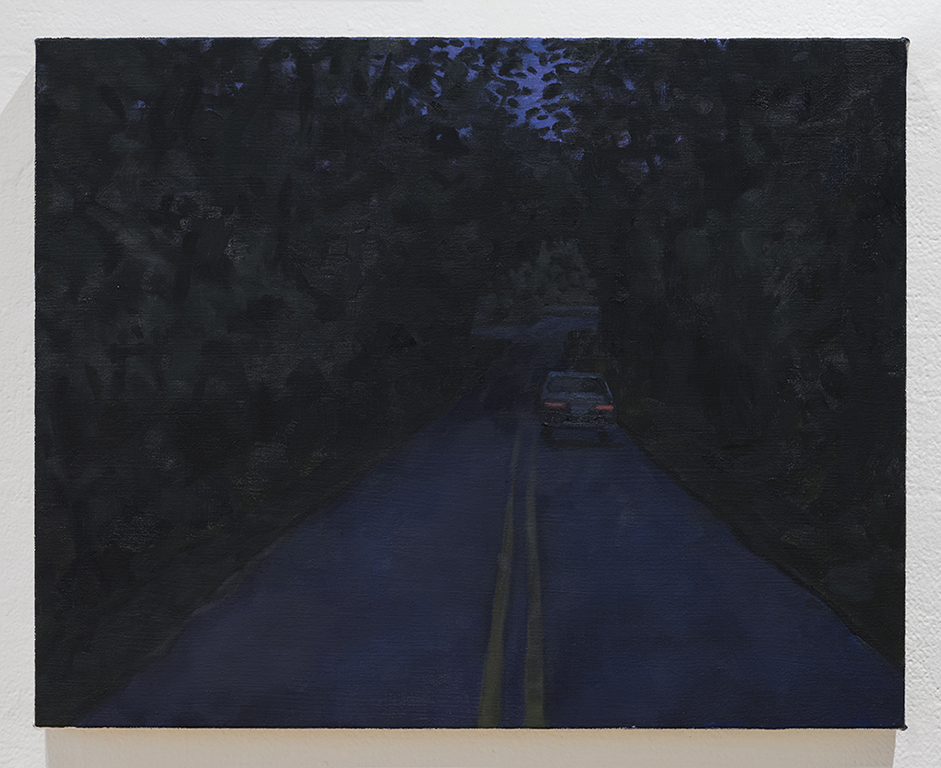

Near the drawings is The Long Dark Bright (2022), a solitary painting in dark blues and greens that depicts a car on a highway at night, its taillights a subdued red. The effect is sinister, brooding. Around the corner, above the gallery’s front desk, hangs another solitary painting, presenting a rectangular, rustic Arts-and-Crafts-style gridded window, hung on the interior with a patterned curtain, mostly drawn. As the window fills the frame, the painting itself becomes a window of sorts, and indeed, it is titled Window (2022). Looking through it, however, little can be gleaned except a sense of antiquity and perhaps destitution.

It’s difficult not to find something of the gothic in Skahan’s work, not only in this last work and her house series, but also in the highway scenes, which wend their way through two of the paintings. In these, I saw elements of David Lynch, but the artist told me that for her, the highways were based on screen captures from TV series, such as the documentary Unsolved Mysteries (on air sporadically since 1987) or the first season of the celebrated police procedural True Detective (2014)—not to mention, she added, the experience of being a lone woman driving along deserted rural highways for her residency. Or, for that matter, the simple fear of travelling into the unknown.

To be sure, in the Québec backwoods country of maple syrup and Ti-Jean, you are unlikely to happen upon a Carcosa, such as the one in True Detective, fleeing a machete-wielding madman through the ruins of an overgrown Spanish fort. Nonetheless, the capitalist world of the current epoch is a darkening place in its own right, and for artists—living how we live, earning how we earn—the road ahead is looking like a night drive.

Edwin Janzen, a visual artist, lives in Montréal and works in drawing, collage, installation, digital printmaking, video and other media. He completed his MFA at the University of Ottawa in 2010. Also a contract writer and editor, Janzen has published in Border Crossings, Canadian Art, and elsewhere, and has written and edited for numerous individual and institutional clients.