FIFA 2023: Afterimages and Reflections

March 14 –

March 26, 2023

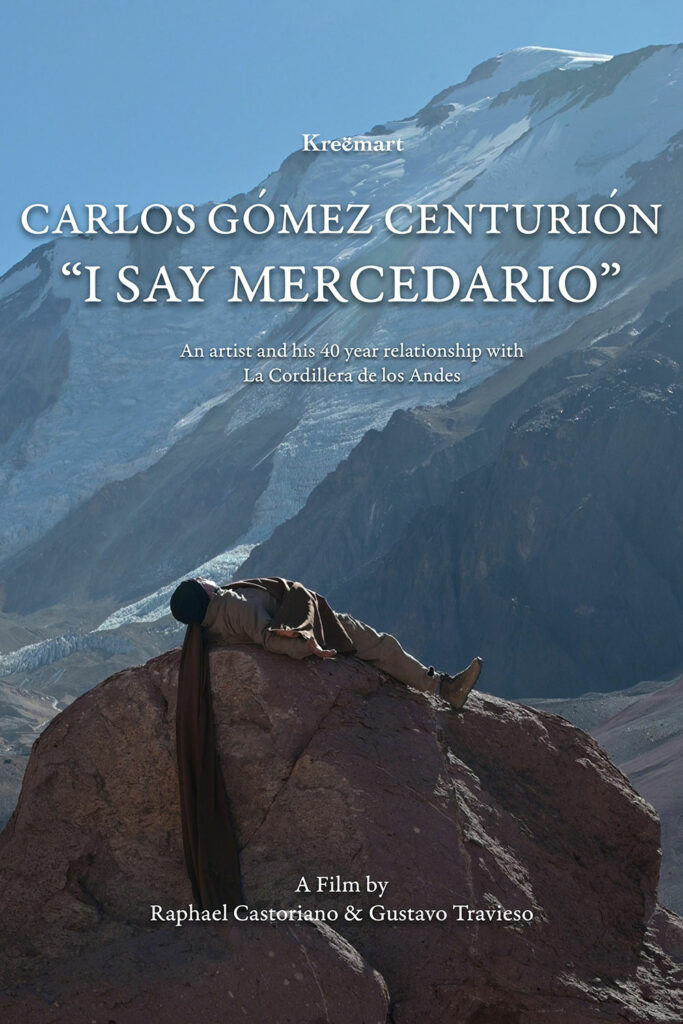

Raphael Castoriano and Gustavo Travieso, Carlos Gomez Centurión: I Say Mercedario, 2022

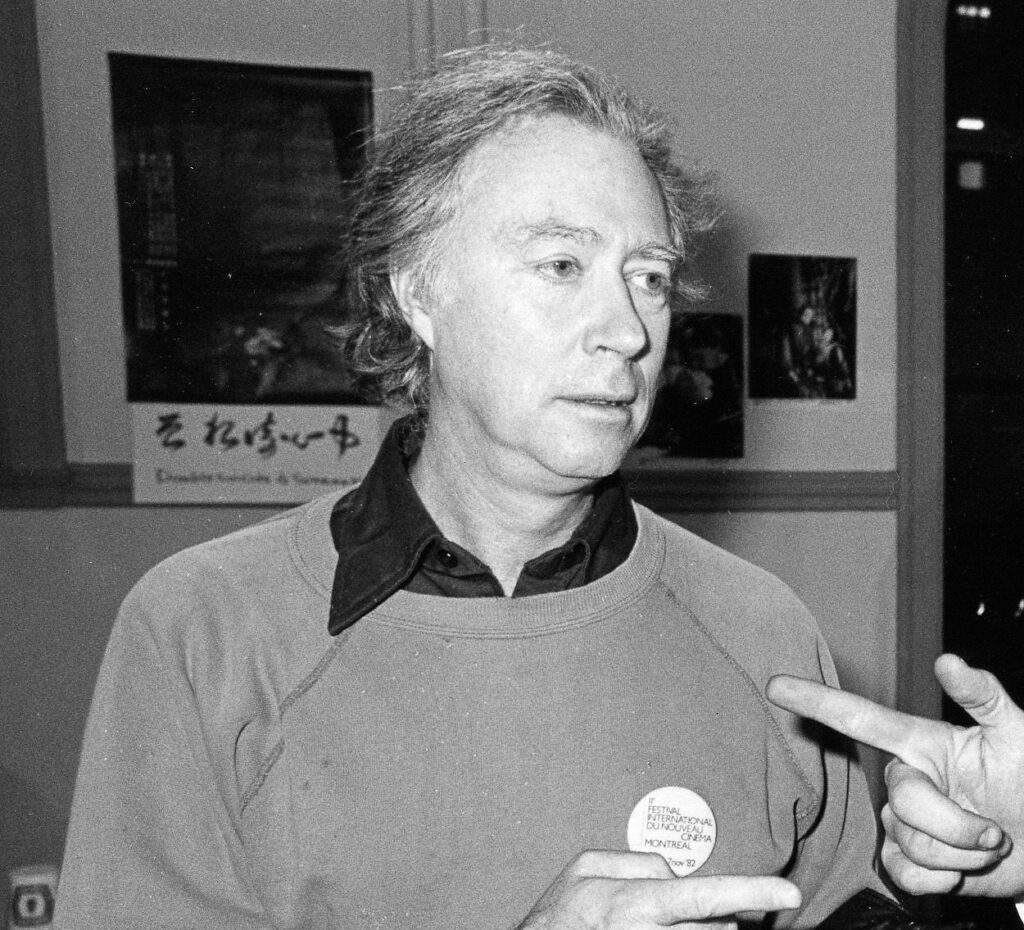

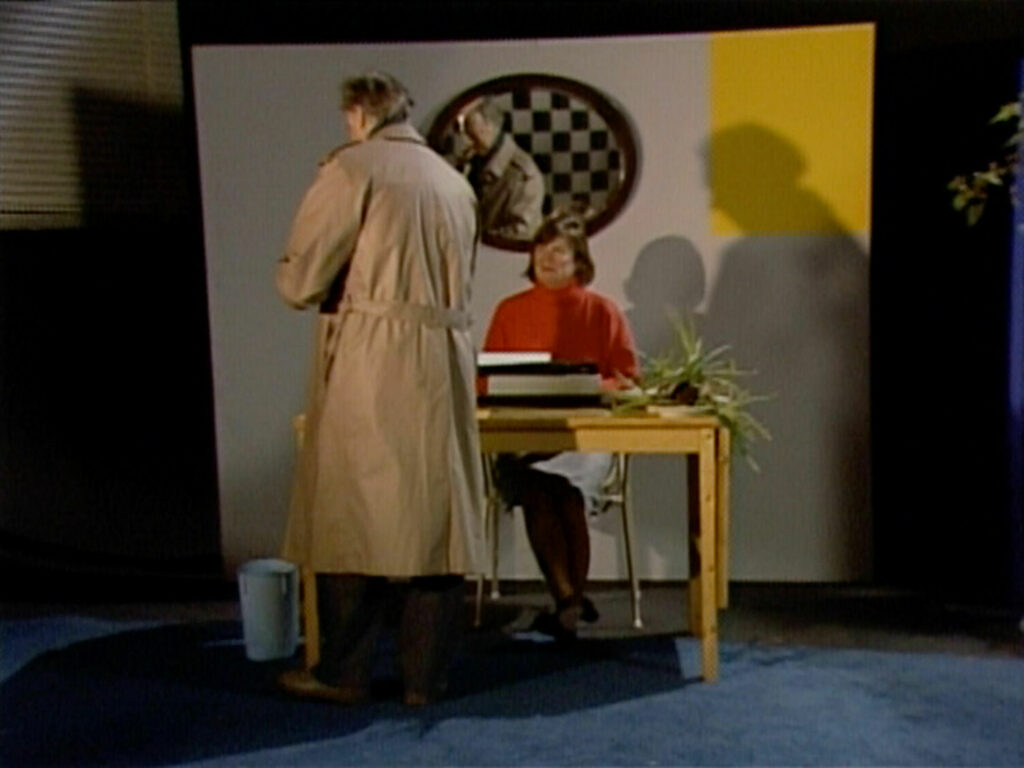

Michael Snow, WVLNT – WAVELENGTH For Those Who Don’t Have the Time: Originally 45 minutes, now 15!, 2003

Michael Snow, See You Later / Au Revoir, 1990

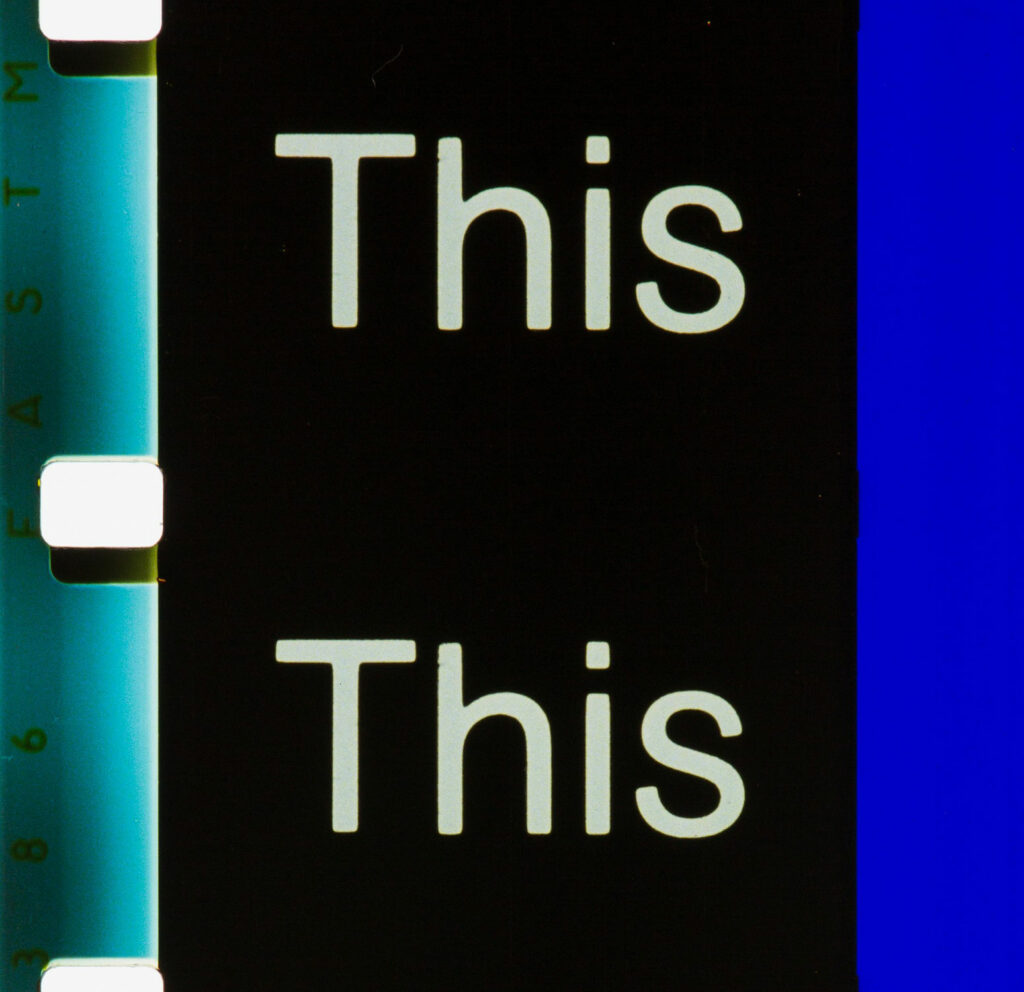

Michael Snow, So is This, 1982

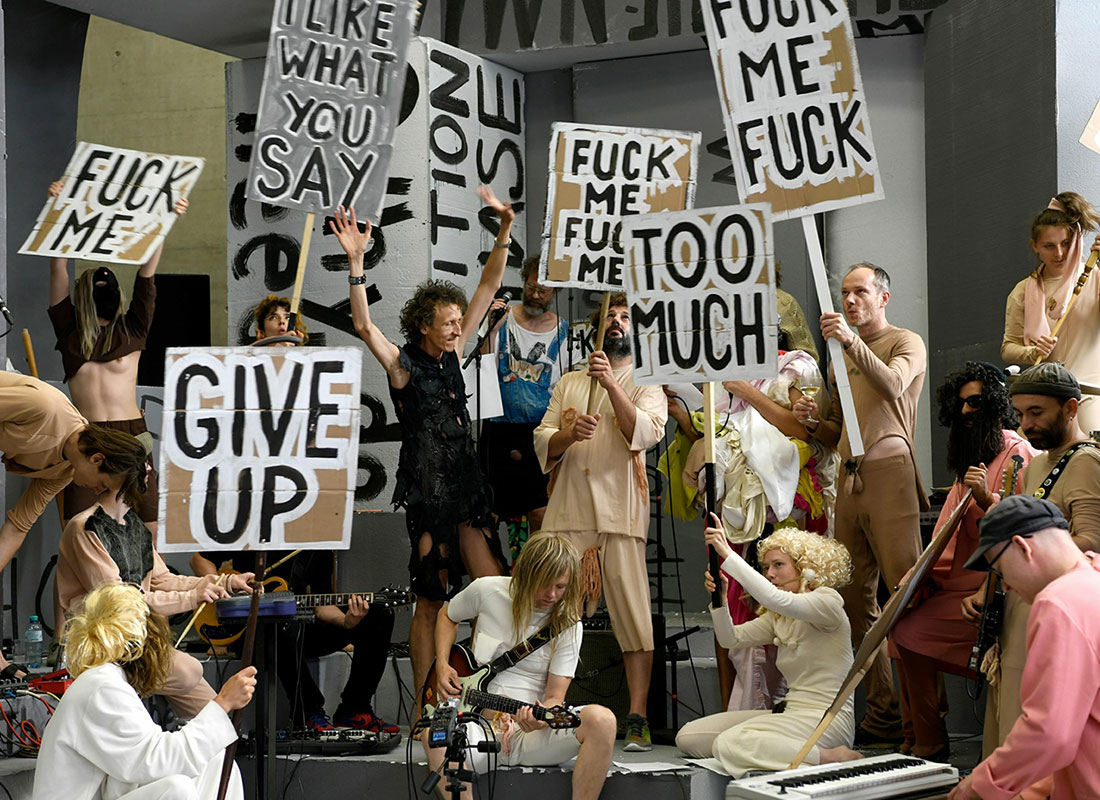

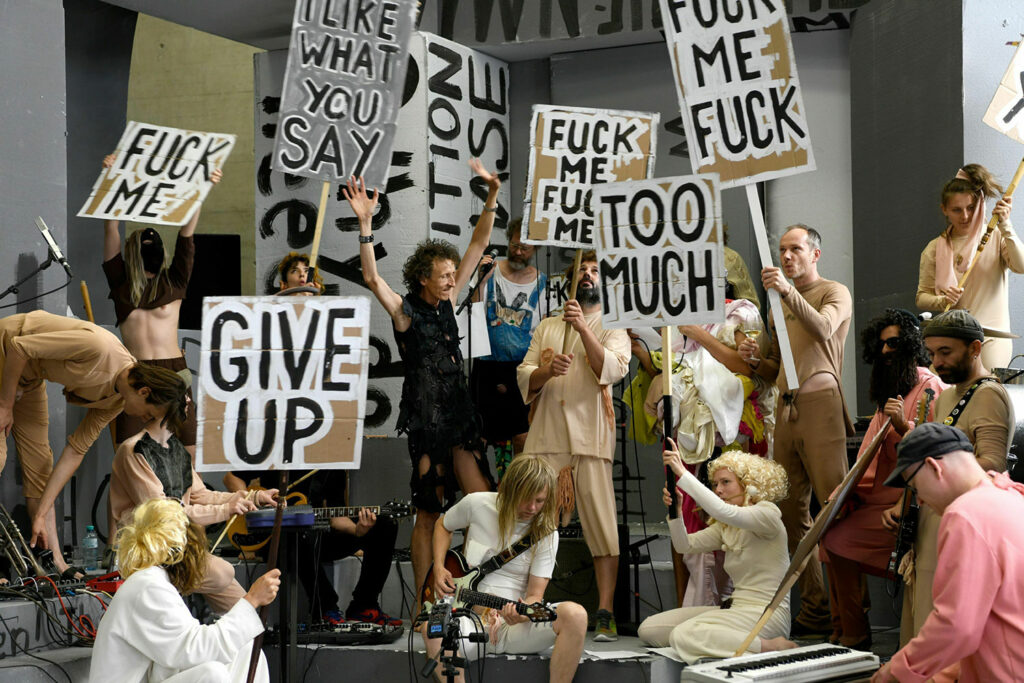

Liam Gillick, Ali Janka, Florian Reither, Tobias Urban and Wolfgang Ganther, Stinking Dawn, 2023

The 41st edition of the Festival of Films on Art (FIFA) cast a large and festive net to usher in this first post COVID-19 pandemic in-person event. In addition to a copious offering dedicated to the arts in a broad sense, the festival provided a fine selection of films focused on the visual arts per se. For this overview, after viewing a wide gamut of films, I narrowed my choices down to three films that speak more directly to developments or issues related to the contemporary art domain.

My first selection, the short film Carlos Gomez Centurión: I Say Mercedario (2022) that Raphael Castoriano and Gustavo Travieso directed and produced, caught my attention due to both the beauty of its faraway images and the timeliness of its subject matter. The film accompanies the Argentinian artist Carlos Gomez Centurión’s venture to capture the majesty of Mercedario mountain (6,720 m) and its associated glacial valley. For over 40 years, this remarkable artist has devoted his artistic practice to portraying the Andean landscape’s upper ranges. In order to bring greater visibility to this artist, who is not very well known beyond his homeland, Castoriano and Travieso approached him under the auspices of their NYC-based art production centre Kreëmart and offered to produce and direct a film depicting his creative process in these extremely remote territories.

Given the inaccessibility of the El Mercedario location, the filmmakers had to lease over forty mules to carry the equipment and crew members. In addition, they also made judicious use of a drone camera to reveal otherwise unattainable perspectives of the glacier valley and peak. Shot without voiceover commentary, the film consists of a series of stunning shots that show the artist as he applies his open-air painting method to create his large-scale landscape works. Through a series of remarkable bird’s eye views of the advancing mule caravan casting long shadows and vertiginous drone-assisted travelling shots up into the narrow cliffs, the images communicate the sense of awe that clearly animates the painter before this sublime mountainscape. The film is at once a portrait of the landscape and a portrait of the artist representing this boundless pristine setting.

By way of an unobtrusive and sensitive filmic approach, Carlos Gomez Centurión: I Say Mercedario succeeds in communicating the sublime feeling at the root of Centurión’s vision, which can be inscribed in the lineage of the romantic aesthetic tradition. It is indeed the characteristically romantic notion of the sublime, or more specifically the Kantian dynamic sublime that lingered in my mind after viewing the film. For Kant, the dynamic sublime is an impression of immensity that triggers awe, terrifies and dwarfs us as human agents, while it also “dynamically” stirs our capacity to reflect and act through our aesthetic response to such a phenomenon. In addition to the sublime beauty Carlos Gomez Centurión evokes in his works, he also bears witness to the fragility of the grandiose glacier of El Mercedario’s landscape, which is, as the film’s credit roll informs us, also receding rapidly due to climate change. The film’s images are thus also a call to become dynamically responsive to how we are all intimately connected to this nature and complicit in its destruction, and to remind us that it is in our collective power to act and halt processes that are not only causing such sublime beauty to disappear, but also threatening the very viability of our planet.

My next film selection led me from the romantic sublime and its boundlessness to Michael Snow’s highly structured works presented as part of the FIFA experimental section to honour the memory of the recently deceased Canadian artist. For this tribute, curator Nicole Gingras put together a very judicious program comprised of the films WVLNT – WAVELENGTH For Those Who Don’t Have the Time: Originally 45 minutes, now 15! (2003), So is This (1982) and See You Later / Au Revoir (1990). Rather than dwelling on the individual films here, as they have all received ample commentary in various art history and film studies texts, I will highlight the unique experience—for me at least—of seeing all three films in succession on a large screen and in a packed house.

Gingras’ curatorial selection foregrounded the essential qualities of Michael Snow’s filmmaking, which features an experimentation with the film image’s spatiotemporal unfolding (WVLNT ), a reflection on duration, language and the filmic “signifier” (So Is This), as well as a rigorous yet playful exploration of rhythm and the perceptual possibilities inherent in his medium of choice (See You Later / Au Revoir). All three films bear witness to this pioneering artist’s methodology that uses a pared down, meticulously composed and strictly measured approach to cinema. These are all qualities that exemplify the Kantian aesthetic notion of the beautiful—in contrast with the sublime—as something that is bounded, well measured and proportioned. After seeing this succession of beautiful, yet quite demanding works, I walked out of the cinema feeling calm with a sense of having truly been brought to reflect on the dual sense of seeing again and engaging deeply in thought.

In this spirit of thoughtful repose, I exited the tribute screening and went to catch the North American premiere of Stinking Dawn (2023) presented one block over. Early in the screening, my pensive mindset was quickly pulled into a diametrically opposed register of frenzied deconstruction and irreverent chaos. As I watched the film’s inventively grotesque and humorous scenes unfold before my eyes, I experienced a mixture of amusement, surprise and, at times, unease.

Contemporary British artist Liam Gillick directed Stinking Dawn, which features the Austrian performance troupe Gelatin and a broad range of unwitting extras, who take us on a vertiginous ride into an increasingly delirious state of collapse that lays bare the contours of a “post leftist capitalist dystopia.” The feature film was shot during an exhibition-installation-performance that freely unfolded in the Kunsthalle Wien from July 4th to 13th, 2019. The script, loosely based on French philosopher Gilles Châtelet’s 1998 book To Live and Think Like Pigs—The Incitement of Envy and Boredom in Market Democracies, guides the film, which follows “four pathetic young snobs” along a downward spiral brought on by their envious and bored reactions to a neoliberal world that champions self-fashioning and consumerist indulgence.

Per the opening captions, we are informed that all these protagonists have recently inherited businesses of their own, but that what they really want to do is play in a rock band. The ensuing action is structured as a series of vignettes, portraying each character’s self-indulgent and oppressive activities. Their stories, as well as that of Gillick playing a manipulative nightclub owner, lead us through a modular set of faux-stone polystyrene blocks that the protagonists and extras rearrange into various architectural forms throughout the film, constructing a grotto, a mausoleum, a prison, a temple with colonnades and, most centrally, a nightclub. In an opening scene, one of the four young snobs pays a visit to a grotto in which workers serially produce ink-wash paintings, holding a brush in their sphincters and wiggling their behinds to create movement. After evaluating the quality of this bizarre art factory’s productions, one of the protagonists chooses his favourite work and then proudly heads out of the cave to sell it in exchange for cryptocurrency.

The destinies of the other three “pigs” follow a similar pattern of twisted transgression and burlesque campiness. To amplify the vacuity and general disorientation of their respective undertakings, the walls and blocks of the modular set are covered with a series of graffiti tags such as “We are fashist [sic] worms,” “You are like the others,” “Blasé poser,” “Give up” and other similar lofty pronouncements. The general atmosphere here is decidedly grotesque and carnivalesque, which Bahktin has defined as a worldview, expressing joyous irreverence, mockery of the established order and a celebration of the lower bodily stratum. Indeed, the lower bodily functions, with a particular focus on the ass and the scatological are abundantly depicted in this topsy-turvy spectacle. For instance, take one of the film’s closing scenes: with the night drawing to a close, the protagonists stage a final paroxysm of a wild happening in the nightclub space. As the foursome’s band jams frantically away, a small group begins to wriggle on the dance floor where they produce a lightshow with green laser beams, emanating from their bared rectums. A mascot pony then approaches to deposit a profuse amount of mock scat on the art factory owner protagonist, who proceeds to feverishly wallow in it until he is completely covered and apparently satiated. The literalness of the film’s title “Stinking Dawn” becomes glaringly apparent here. As daylight approaches, a gang of axe, knife and chainsaw wielding Vikings on ride-in costume horses enter the premises via an elevator and proceed to slaughter the protagonists one after the other, while the entire set tumbles down all around. A final state of utter collapse thereby concludes this last chapter of the destinies of pathetic young snobs in an unravelled political environment.

This campy and grotesque exhibition-installation-performance film, with its echoes of Viennese Actionism, Buñuel, Pasolini, Ulrich Seidl, John Waters and others, elicits a mixed affective state of amusement, bewilderment and discomfort. The somewhat jumbled, at times belaboured, yet always humorous and engaging exercise in neoliberal psychosocial disarray is quite ambiguous in its diagnostic. On the one hand, this acerbic, no holds barred, art-mediated critique offers a thought-provoking commentary on our dire post-Trumpian, tensely polarized Zeitgeist. While, on the other, it leaves one wondering if this carnivalesque tomography of self-delusion and collapse doesn’t teeters on a thin line between satirical condemnation and a nihilistic surrender or complacent wallowing in the very state of affairs that are in the crosshairs of its critique. Regardless, the film clearly brings substance to the observation that “it is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism.”

A film festival such as the FIFA, makes it possible to embark on various screen-mediated journeys to other places, experiencing other perspectives and realities through the prism of the arts. Along my particular travels, the films reviewed above, among others, allowed me to encounter artistic worlds expressed in several distinct aesthetic registers, from the romantic boundlessness of Carlos Gomez Centurión: I Say Mercedario, to the in-depth experience of Michael Snow’s structural cinematic art with the Focus Michael Snow tribute in three films, and the grotesque aesthetic of Stinking Dawn with its darkly humorous take on our current conjuncture in the ruins of neoliberal capitalism.

Bernard Schütze is an independent art critic and curator. His essays have been published in numerous art magazines. He has written various catalogue articles and artist monographs, and has presented talks as part of several art-oriented events mainly in Canada and Europe. Originally from Germany, he lives and works in Montréal.