Empathetic Responses: Emily Falencki and Eric Fischl

The upheavals of the 20th century—the end of a European political order that had held sway for almost a thousand years, two world wars, the rises and falls of imperialism, communism, and fascism—have had echoes that are still reverberating. In fact, given our present reality, aftershocks are perhaps a better analogy than echoes—the primary quake may have happened decades ago, but the aftershocks are still knocking down well-established assumptions.

Responses to this sense of upheaval are as varied as the people and societies affected, and there is certainly no consensus—elites, governments, citizens—all seem to be reeling from shock to shock. About all that is certain is that many of us are uncertain, fearful, and anxious.

These upheavals, described by Sigmund Freud as psychic wounds, have indelibly marked our history. While their presence is constant, it has subsided from a central concern to a background hum—the ground more so than the figure. Artists, through the works they make, can provide clues to how the wounds are being treated—can provide a way to see whether a society is being resilient, or is buckling under the pressure. Many artists, like so many of their fellow citizens, seek to escape from the uncomfortable realities we inhabit today—just witness the preponderance of angels, dragons, zombies and alternate histories that make up so much of our popular culture. Sometimes this escape provides a mirror back to our current reality, metaphor and analogy serving as critical tools of analysis. Too often, a vampire or zombie is just a vampire or zombie—entertainment rather than a lens, an opiate rather than a spur to thinking. Others meet the world as they find it.

Two artists whose recent work addresses some of our cultures many wounds are Emily Falencki and Eric Fischl. Specifically, their works look at some of the most disruptive instances of the effects of these wounds: the effects of the Second World War and its aftermath, and the ongoing battles of the “war on terror” and its victims.

Canadian artist Emily Falencki, whose exhibition of paintings inspired, in part, by her Polish/Jewish grandparents’ survival of the Holocaust (and the deaths of most of her extended family), is currently on view at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia’s Western Branch in Yarmouth, following its exhibition in Halifax. Falencki makes art that portrays the victims of violence, whether state sponsored or as the result of individual criminality. Consistent though, is the fact that the victims she depicts have suffered from violence fueled by the cancers of racism, misogyny, and civil strife that seem to be the inescapable symptoms of our wounded age. The images she gleans from the media, and recreates as her own images, are not of victims or chance or accident, but of human design.

These days, we are bombarded with images coming at us from the multiple screens that bound our personal worlds, and we grow ever more inured to their potential impact. The cliché from the days of “yellow journalism” asserted that, “if it bleeds, it leads.” But now, it often seems that many of the images competing for our attention are all too bloody. What can “lead” in this context? And what happens, in particular to us, as viewers, when images of pain and suffering cease to shock? Emily Falencki’s paintings insist on asking these sorts of questions. Her images are all too familiar—both specifically and generically—and she reinvests them with power, primarily through reinserting the images into the world of our time and space. Unlike the 24-hour news feed, Falencki’s images release their impact slowly, they unfold under our gaze, and re-present that which we already know, in a manner that makes that knowledge harder to dismiss, or discount. It is not shock or awe that she is seeking in her work, these are not attempts at finding the sublime in human suffering. Rather, she is striving for empathy—we are brought to feel for the others depicted in her work; we have time, as we gaze at these paintings, to consider the pain of others, and to mourn.

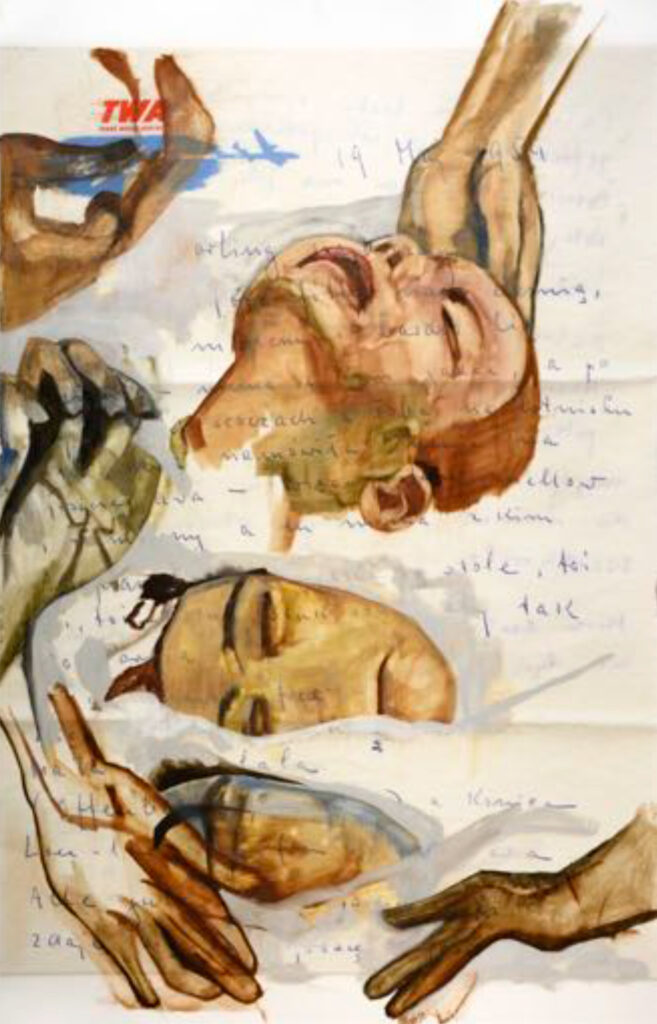

Falencki’s process is meticulous and labour intensive. She begins by making her own gesso in a traditional, pre-modern manner. Then she starts to paint: she works in layers, building up rich surfaces, parts of which she abrades and even erases. Her works go from the local to the universal. Recent paintings such as Mira River and Loretta combine images from the Syrian civil war with newspapers photos depicting young women who were murdered in Nova Scotia. Violence, these paintings argue, is always immediate—it always is “local.” Her recent work is in two series: The Missing and The Letters. The Missing comprises works derived from media images of people who have been killed by violence, or who are mourning those who have been. In Mira River, for instance, images of a young woman and a man screaming are juxtaposed. The woman, whose image has the direct gaze of a school or driver’s license photo, was named Laura Jessome. The 21-year-old’s body was found in the river, crammed into a hockey bag.

The male figure is from a media source, an image of a man screaming his grief and rage after family members were killed in an attack in Syria. The overall work

is remarkably powerful—whether or not one is aware of the origins of the source imagery. For Falencki, the granddaughter of holocaust survivors, the sense of people being missing, or that they can be erased by history and events, is a palpable link to her own history, one where the majority of her family members, their communities and their traditions, were wiped out of existence. Ultimately, all tragedy is individual. In her series The Letters, similar imagery as that used in The Missing, is layered atop scanned images of letters between her grandparents, and between her grandmother and great-grandmother. Images of the envelopes, often franked with Nazi symbols, are also used as grounds for paintings.

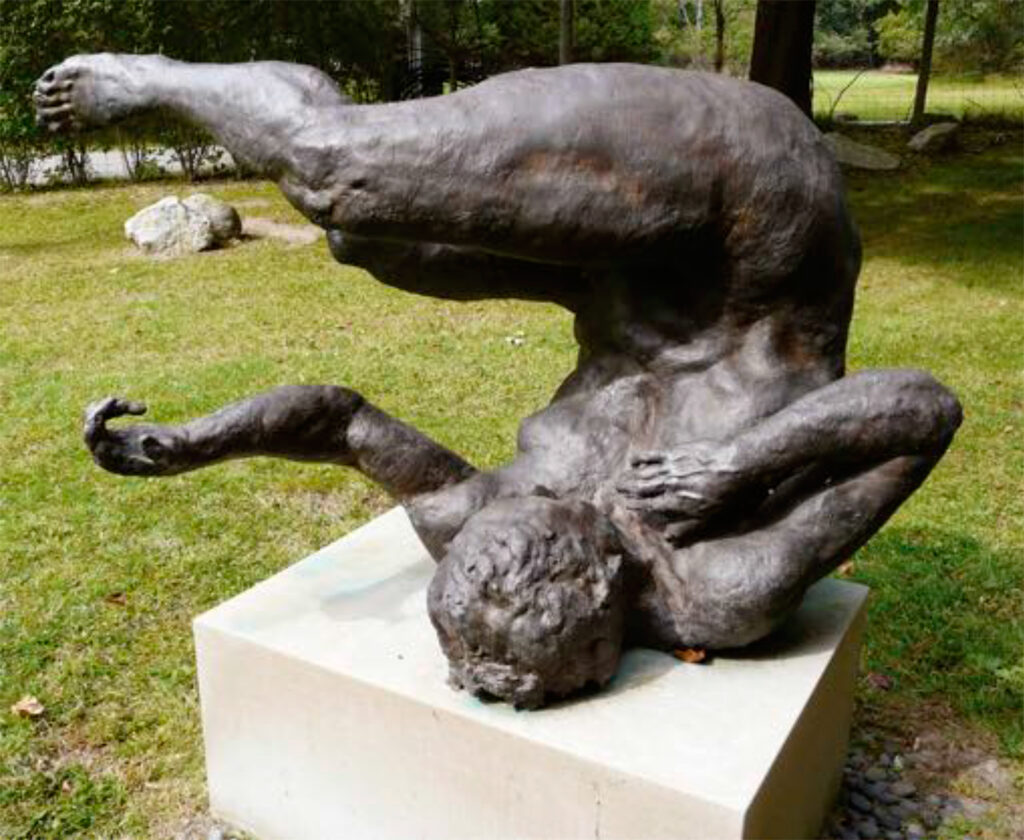

This interaction sustained with images of the victims of violence is a constant in Falencki’s work. For American artist Eric Fischl, it has been more of a response to one sudden traumatic event: the attacks on the World Trade Centre on September 11, 2001. His sculpture Tumbling Woman, made in response to 9/11, which, as a New Yorker, he viewed on television along with much of the world, is a direct response to viewing figures jumping out of the burning towers. His controversial sculpture, Tumbling Woman, created in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, was censored when it was exhibited a year later at Rockefeller Centre. Emotions, as the artist acknowledged at the time, were simply too raw. A version of the work (Fischl has made several casts of the bronze, larger than life-size figure) is currently on view again in New York, as part of the exhibition Rendering the Unthinkable at the 9/11 Memorial Museum.

In the years since September 11, 2001, it is the twin towers, and their absence in the reconfigured skyline of New York that has come to be the symbol of that day. But it is the so-called “jumpers” whose images resonate most poignantly—each falling figure, in their singular descent, somehow personalized the tragedy of 9/11—their anonymous individuality made their humanity manifest in a way that reports of thousands of deaths in the towers simply could not. Eric Fischl’s sculpture Tumbling Woman, is a monument to the jumpers, yes, but it is also a profoundly human response to a tragedy—his figure, portrayed in the instant before she hits the ground, harks back to some of the great sculptures of tragedy: Rodin’s Burghers of Calais or The Falling Man, or Michelangelo’s The Dying Slave, for example. It is a sculpture seemingly outside the contemporary experience, not part of the current sculptural conversation, but rooted in the history of statuary and religious iconography. This work is so powerful, of course, because of its shared weight of history—it references a shared experience, one so powerful that its memories can still move people to tears. It is often misunderstood, initially rejected by some as opportunistic and insensitive, but over time its profound sensitivity and humanity has shone through. All too human, it seems almost ahistorical. As Albert Camus wrote in his essay The Rebel:

The greatest and most ambitious of all arts, sculpture, is bent on capturing, in three dimensions,

the fugitive figure of man, and on restoring the unity of great style to the general disorder of gestures.1

I’m not sure if such a thing as “great style” is possible anymore, but if it is, Tumbling Woman approaches such a state.

Both Falencki and Fischl respond to horror with empathy—their works are not angry, do not evoke fantasies of revenge; the artists acknowledge their weakness and frailty in the face of evil, and respond by reaching out a hand to the suffering. Both artists make the fugitive figure of humanity their subject.

The empathetic response of each of these artists to horrific instances of inhumanity is inspiring and humbling—empathy can be very difficult to summon and to sustain, and it forces complex and often difficult negotiations of position. It seems, that like satire, empathetic responses can be easily misunderstood. But it is where we must start to address our collective and individual wounds. After all, from empathy flows understanding, confession, forgiveness, and, eventually, reconciliation.

In the Western world, the Modern era, with its attendant decentering of humanity as the centre of the universe—physically (Copernicus and eventually Einstein), naturally (Darwin) and spiritually (Nietzsche, Freud, Marx and others)—in tandem with the resultant unbridled rise of technology, caused, as Freud famously contended, wounds. These narcissistic wounds, the decentering of the human from our world view, have left our cultures reeling, seemingly lacking any moral compass or ethical “red lines” that will guide the behaviour of states and individuals alike. The current abyss, which we fear looks back at us, is not nothingness, but nihilism—the belief that life has no meaning, and its attendant tenet that murder can be logically justified. As Alert Camus pointed out in The Rebel, “The wound that is scratched with such solicitude ends by giving pleasure.”2 An optimist might point to the rule of law as a bastion against nihilism. Laws have supplanted morals, and that is probably to the good—but we remain wounded, and the cold comfort of the legal system does not provide much of a balm.

Empathy does. Art of course has always depended upon empathetic responses—the reception of a work of art by another presupposes that the viewer will be open to the work, will put themselves in the position of thinking along the lines laid down by the artist. Communication should be, and understanding must be, empathetic.

Perhaps in our postmodern, media benumbed age, the only kind of “great style” possible is to embrace the individual humanity of others, to acknowledge that everyone matters equally, that all human suffering, each human loss, diminishes each of us. We are none of us islands. Camus’ claim for sculpture, it seems to me, holds true for Mira River as much as for Tumbling Woman. Great style, in a shattering world, is, perhaps, an empathetic response. Through empathy, and its attendant virtues of compassion and forgiveness, we, as societies and as individuals, can reconcile our grievances, and, eventually, can bind our wounds and heal.

Ray Cronin is a Nova Scotia-based writer, curator and arts consultant. From 2001-2015 he worked at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia as Curator (2001-2007) and as Director and CEO (2007-2015). He is the founding Curator of the Sobey Art Award. He is the author of numerous catalogue essays, as well as articles for Canadian and American art magazines. He was the Visual Arts Columnist for the Daily Gleaner (Fredericton) and Here (Saint John). The Arts Canada Institute and Gaspereau Press published his books Alex Colville: Art and Life and Mary Pratt in the fall of 2017.