Cartography and Contemporary Art. “The Body of the Place.” 1

In the 5th century B.C., when Herodotus sought to understand the causes of the war between the Greeks and the Persians, he painted— with the help of words — a world in the shape of a skull. Such an anthropomorphic representation immediately takes us to the core of the problematic inherent in the composition of cartography: in attempting to visualize the organization of territories in the most scientific manner possible, it is himself that man represents, it is himself that he seeks to draw.

“The world is small. The dry land is six parts of it; the seventh only is

covered with water. Experience has already shown this, and I have written

of it in other letters, and with illustration from Holy Scripture concerning

the situation of earthly paradise, as Holy Church approves.” 2

Christopher Columbus’ testimony, about 2000 years later, is also that of a man shaped by his time, living in a century that had a finite and rationally ordered representation of the world. In his mind, through calculation he could find navigable sea routes to India. Man is at the centre of creation: the elements, animals and savages alike are ordered according to his will. It is stirring to take stock of both the strangeness and scantiness of this still medieval world: the often luxuriant lands are inhabited by extraordinary humans and animals, concentrating creation’s incredible possibilities within a small parcel of land. Already during the age of discovery — as is borne out by the portolanos exhibition3 l’Âge d’or des carte marines. Quand l’Europe découvrait le monde that just ended at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF) — maps where considered works of art that were drawn and illustrated by artists and illuminators. Some of these maps travelled on the high seas, others where exhibited in the chambers of the powerful. Their public presentation was intended to instruct, celebrate the marvels of divine creation and be a source of pleasure. The artists who illustrated them invented apparently rational populations: wild beasts and antipodes correspond to the continent’s climate and disposition. The world appears above all as a domain at the service of humankind, a place of wonder, there to be explored. Based on testimonials, sketches, and the scientific knowledge of the era, the 16th and 17th century artists created mono-focal maps that celebrated Western dominance over all the earth’s lands and seas.

In introducing the void of the infinite, the Copernican and Galilean revolution clashed with this golden age of a fully self-confident humanity. If the universe has no limits, humankind can no longer occupy the centre. “The whole visible world is only an imperceptible atom in the ample bosom of nature.” Ancient assurance is followed by modern insecurity.4

This, no doubt, is one of the reasons why the production of maps steadily increased during the modern period. The stable and knowable world was replaced by cartography that fluctuated and evolved according to the latest discoveries, changes in borders or population displacements: the world is no longer reducible to a divine creation that one need only discover, it is henceforth composed by humankind itself. The 20th century witnessed the apex of this tendency: maps were redrawn annually, despite the fact that our knowledge of the territory had become more and more certain. We are in fact caught in a paradoxical movement that is twofold: science now teaches us that other galaxies millions of light years away exist in the universe. Humankind’s place in the universe is even more microscopic than that of the mite mentioned by Pascal.5 Yet, in contrast, our knowledge of the earthly world has become more refined and so precise that it has caused all the terra incognitae to disappear. Compared with the meticulous macrophotographic observations of the earth’s surface, we have become giants. Through human consciousness, the infinitely big encounters the infinitely small.6

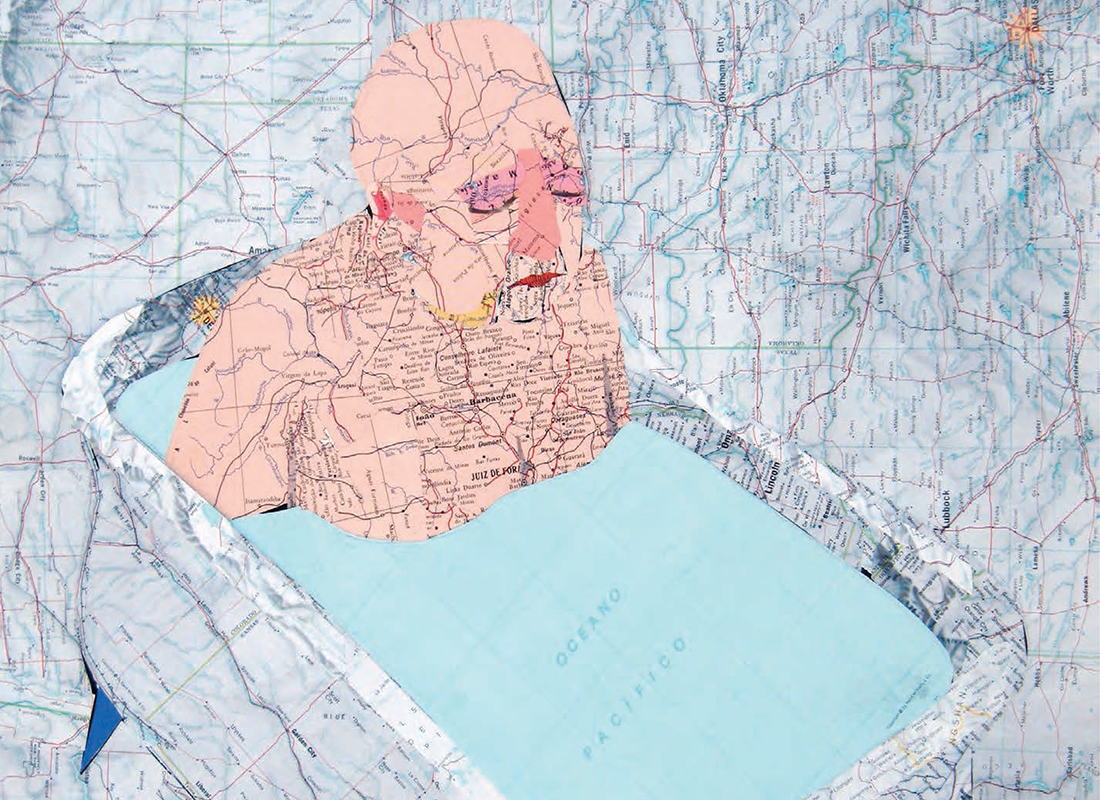

The backdrop against which Voltaire drew his dizzying Micromegas7 figure becomes apparent: that of a man torn between two infinites, conscious of the relativity of all things in a world abandoned by divine rationality. In an era in which space exploration has made exile from of this world possible, the question of humankind’s situation becomes even more problematic. Between a manifestly, fully mastered terrestrial space and the unknowable infinity of the universe, how is one to find one’s place? Joao Machado’s work, using a confrontation between the map and the figure, brings to light the difficulty of reflecting on man’s situation in this world. Man’s presence is overwhelming, but the delicate networks that run through him reveal his disorientation before the multiplication of possibilities. In a world where knowledge and action have become accessible, the hand of man builds new labyrinthine spaces on its surface: underground networks, artificial plateaus, vertical constructions and road networks that make existing space more complex.

Christopher Columbus noted the smallness of the world to underline its perfection. For the moderns, this smallness has become the symptom of confinement. Like in Joao Machado’s work, contemporary man feels cramped on earth and threatened in the universe.

In Tristes Tropiques,8 Claude Lévi-Strauss paints a stark picture, as we well know, of travels and explorers. He sees this frantic quest for new unknowns as the equivalent of initiation rites that adolescents are subjected to in many cultures: fear, wounding, scarification and fasting appear to be necessary moments in a self-constitution. This appetite for travel was still current at the beginning of the 20th century and up until the 1960s: young ethnographers went off to explore distant territories where they hoped to encounter still virgin lands and people. When it became evident that their hopes would be dashed, these adventurers did not hesitate to discreetly modify reality, making “savages” pose in traditional garb, while excluding any reference to Western civilization from the photograph. What happens to self-constitution in a thoroughly marked out, familiar environment, where it has become impossible to lose one’s way? It is henceforth necessary to develop new cartographies that testify, for example, to ever-changing landscapes or behaviours. Today’s explorers have abandoned the quest of the faraway to come back to a proximity that is ultimately just as difficult to know. Extensive research has been replaced by an intensive inquiry. Artists have invented new unsettling spaces in which we struggle to find our way.

Artists are thus the alter egos of yesteryear’s explorers. There where the known makes any risky exploration impossible, where all danger can be averted, where GPS and other navigation technologies show us the way without possibility of error, artists reintroduce the uncertainness of surveying and labyrinthine space. In the 1960s, Richard Long (A Line Made by Walking, 1967) was a pioneer of this way of re-appropriating physical space, when the possibilities of virtual travel and the automobile’s widespread use had transformed the map into an abstraction.

The BNF exhibition displayed how the famous portulanos may have been conceived in the 17th century. Lodged on ships, the cartographers took notes of the specifics regarding the lands they passed and the seas they crossed, and they measured the direction of the winds and the location vis-à-vis the poles. This particular and necessarily subjective viewpoint is something that the contemporary cartography tends to replace with the universal and indifferent vantage point of technology, thus objectifying a space that no longer needs to be experienced. Richard Long and, more recently, the Chinese artist Qin Ga (The Long March) have re-appropriated territory through physical confrontation with it and have reendowed the map with meaning: http://www.vvork.com/? Contemporary artists seek to re-establish a relationship to the body in map making. Where the map indicates even contours and stretches of uniform colour, Richard Long experiences the unevenness of the disturbed landscape he has crossed. The map of China is progressively tattooed on Qin Ga’s body, branding the visited cities onto the traveller’s skin. The abstraction of territory in the mind is replaced by the drawing of the territory experienced. Going against the grain of Michel Houellebecq’s well known statement, according to which the “map is more interesting than the territory,” 9 these artists show that the map diminishes our knowledge of the world’s physical dimension.

The bodily dimension is still evident in Pierre-Alexandre Remy’s work. During the artist’s residency at Domaine de Kerguéhennec (Bignan, Brittany), he got lost in the vast park surrounding the château. Surveying revealed the unevenness of the ground, the streams, paths and slopes that are represented abstractedly on the official national map. From this encounter of the walker’s body with the actual land and the map, the sculpture was created: a work that expresses knowledge (orange for the contours, blue for the waterways and black for the roads) and perception (interlaced paths, superposed strata). This is how Portrait cartographique came to be, a work that combines the flexibility of rubber with the rigidity of galvanized steel: organic and industrial materials, showing both the human and technological approach to the terrain.

How do we locate ourselves in space? It seems that knowing our precise location does not necessarily appease our relationship to the world. The map is too abstract and immaterial and thus indicates our insignificance. The mapped territory reduces urban clusters to simple dots. The imagination, on the contrary, is a way for human beings to appropriate and manipulate space. In his Cours sur la perception (course on perception) Jules Lagneau wrote: “Time is the mark of my powerlessness. Extension is the mark of my power.” 10 Evidently, while time cannot be controlled, if it inevitably escapes me, space, on the other hand, can be traversed, shaped and submitted to the will of the intellect. It is in this light that one can analyze the resurgence in modern works of spaces where an individual can get lost and where he/she can show his/her ability. One need only think of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, Andrzej Sekula’s Cube, Christopher Nolan’s Inception, Tim Burton’s recent Alice in Wonderland or Richard Serra’s monumental works in sculpture. 11

Each of these works presents a quest for identity that is also a conquest. In the Phenomenology of the Spirit, Hegel explained that self-consciousness could only be acquired in the calm rest of unity. It is through confrontation with the world and otherness that the subject succeeds in constituting him or herself as a being in itself for itself. The territory thus must remain the site of confrontation: the good war that Hesiod already spoke of.12 In a world that science attempts to make transparent, art is a way to confront us with opaqueness and mystery. Complicating our relationship with space — obscuring the map — remains the way to give body to places.

-

Pierre-Alexandre Remy, excerpt from the catalogue published by Domaine de Kerguéhennec in 2012.

-

Christopher Colombus, Letter from the Fourth Voyage, 1503.

-

Portulan charts were navigational maps, used between the 13th and the 18th centuries, that provided sailing directions, indicating the location of ports and various dangers associated with them (currents, shallows and the presence of hostile populations, etc).

-

Alexandre Koyré, From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe, Baltimore, John Hopkins Press, 1957.

-

Pascal : Les Pensées n˚ 72 et 793. Éditions Brunschvicg.

-

« For who will not be astounded at the fact that our body, which a little while ago was imperceptible in the universe, itself imperceptible in the bosom of the whole, is now a colossus, a world, or rather a whole, in respect of the nothingness which we cannot reach? », Ibid.

-

François Voltaire, Micromegas, trans. Theo Cuff, New York, Penguin books, 1995, [1752].

-

Claude Lévis-Strauss, Tristes tropiques, trans. John and Doreen Weightman, New York, Atheneum, 1973, [1955].

-

Michel Houellebecq, The Map and the Territory, trans, Gavin Bowd, New York, Knopf, 2012. (Our translation.)

-

Jules Lasgneau, « Cours sur la perception » in Célèbres leçons et fragments, PUF, 1964. (Our translation)

-

Richard Serra, Matter of Time (1994-2005).

-

Hesiod, Works and Days.