Space in question

This summer, if everything works out as planned, artist and geographer Trevor Paglen will launch a reflecting sculpture titled Orbital Reflector into extra-atmospheric space. Produced with a lightweight material similar to Mylar, this work will be affixed to a small satellite placed on board a Falcon 9 rocket, property of SpaceX, the CEO being none other than Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla Motors, the producer of electric cars. When the rocket is more than 575 km from Earth, the satellite will release the self-inflating work into orbit, where it will remain for several weeks. The Nevada Museum of Art collaborated on this project and will show the first model of this satellite.1 Visible to the naked eye at night, Orbital Reflector is a “non-functional” work in which the sole interest is to give viewers on Earth a point of light that will move across the sky. Unlike the thousands of scientific, military or commercial satellites that since the late 1950s have travelled above our heads without us taking much notice, Paglen’s Orbital Reflector, on the contrary, seeks to be visible so that we can reflect on our place in the world. He hopes that this work is able to rekindle our sense of wonder about the Universe. But why should it not also allow us to examine, from a new perspective, the question that philosopher Hannah Arendt posed in 1963, regarding the future of humanity in the era of “space conquest.”2

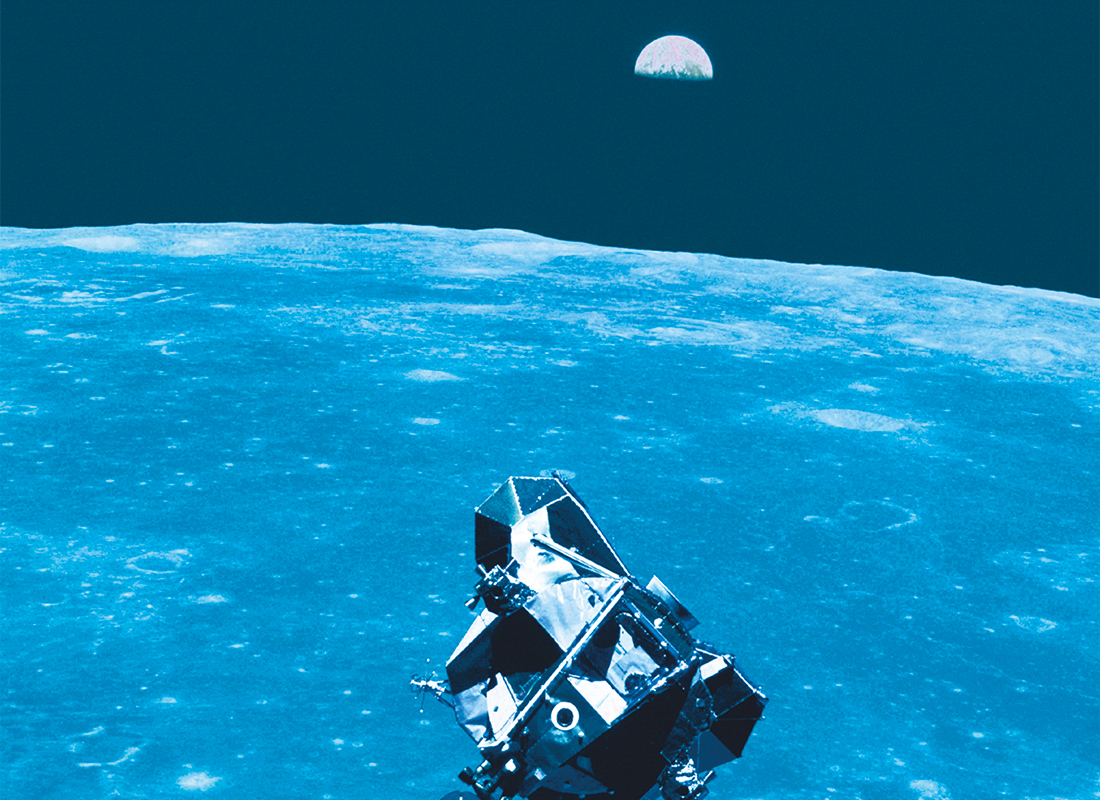

From its stable position at the centre of the world just over four hundred years ago, the Earth has undergone a “cosmic downgrading.” Known since then as the “wandering star” it is a planet among others. But well before we had the possibility of projecting ourselves beyond our home, of beholding the image of the blue planet from an extra-terrestrial perspective, the idea of sending an object or a human being into space had been imagined by authors of science fiction novels or films. Very early on in the 20th century, this desire to explore new spaces also found an echo in the visual arts. Well before Paglen’s project many artists drew up or built prototypes of art satellites.3 Apart from a few more or less fruitful attempts, there is a strong chance that Paglen’s Orbital Reflector will be the most spectacular to date. However, this project that is to cost 1.3 million dollars, presents enormous paradoxes. Though it seeks to provide viewers with a new horizon that could inspire us to dream of a world without borders, the artificial satellite’s launch into orbit requires an infrastructure that is hardly poetic. Well before being an artwork, a satellite entails enormous technical, scientific and economic constraints; for Orbital Reflector, three aerospace companies (Global Western, Spaceflight Industries and SpaceX) are involved. Moreover, extra-atmospheric space is becoming an increasingly coveted “territory.” As a consequence, should one not ask instead whether the “public sculpture” calls our relationship to space into question, since humanity is no longer bound to Earth?

Just over 60 years ago, the exploration of space began against a backdrop of the “cold war” and nuclear threat. It continued with the launch of thousands of satellites indented for multiple purposes, not to speak of the many others known as spy satellites and the vast amounts of space junk dumped into orbit. In short, for decades space exploration had been focused around our planet, but this has not prevented us from aiming higher, travelling several times to our natural satellite and, on some robotic satellite missions, to Mars, our neighbouring planet.

If one is to believe the American president Donald Trump, the US should return soon to the Moon, and certainly to Mars as well. This new phase will probably be carried out in partnership with the business sector. Just recently, in February, Elon Musk, president of Tesla and founder of SpaceX, was celebrating the exploit of having launched a red convertible car into space with Mars as its hypothetical destination. Beyond this spectacular commercial launch, Musk is envisioning even bigger things such as colonizing the red planet in the upcoming decades, according to the docu-fiction Mars.4 Now being “residents of the Universe,” this choice of pursuing our destiny beyond the Earth, is it not a way, as Arendt thought, of hiding our desire to escape the human condition?

Whereas Orbital Reflector has a very limited life span, this is not the case for Paglen’s other work titled The Last Pictures. This is a silicon disk on which a collection of 100 photos, representing various facets of our life on Earth, is engraved. In collaboration with Creative Time, a public art organization, it was launched into space on September 2012, via the communications satellite EchoStar XVI. This disk has been designed to remain in orbit for thousands of years. Furthermore, The Last Pictures, this monument drifting through space, should endure well beyond our own existence.5

This issue of ESPACE on space art opens with Elsa De Smet’s text giving a brief overview of the interest artists took in space during the 1960s, and then focuses specifically on the 1980s and the paradigm shift in space art that occurred then. In this context, she presents American artist Joseph McShane’s S.P.A.C.E. project and French artist Pierre Comte’s ARSAT. However, as we know, fascination with space goes back to the beginning of the 20th century. Cristina Moraru presents artist Arseny Zhilyaev’s exhibition titled Cradle of Humankind, in which he takes inspiration from Nikolai Fedorov, the futurologist and member of the Russian cosmism movement. This philosopher, who believed in the capacity of art to improve life, also influenced the aesthetics of Dragan Živadinov to whom Ewen Chardronnet makes reference. In his text, Chardronnet recalls the main stages of the Noordung 1995-2045 project, which the Postgravityart collective organized and of which Živadinov is a member.

While, quite evidently, space conquest has played an important role in the former USSR and the US; it also has made artists from other countries dream. For this issue, Joan Grandjean turns his attention to artists from Arab geo-cultural spaces who draw inspiration from the imaginary universe associated with the conquest of space. By way of the exhibition Space Between Our Fingers, shown in Beirut in 2015, the author analyzes the phenomenon of Arab futurism and its interest in space, expressed mainly through fiction. Joshua Simon analyzes Israeli artist Noa Yafe’s work Red Star, which evokes the planet Mars. The title of this work also refers to the Bolshevik scientist Aleksandr Bogdanov’s science fiction novel that focuses most notably on the utopian notion of a communist civilization on Mars. Éloïse Guénard, for his part, presents the art practice of Simon Faithfull, a British artist who approaches space from the perspective of Land Art. Planting both feet firmly on Earth, he challenges gravity through his various performances. To complete this issue, there are two interviews with artists, one with Holly Schmidt (Vancouver) and the other with Rober Racine (Montreal), recounting their respective fascination with space. Finally, a portfolio presents the works of artists from Quebec, Canada and abroad, who participated in the PARALLAX-E exhibition, shown recently at the Foreman Gallery of Bishop University.

In addition to this collection of theme essays, the “Events” includes Anne-Lou Vicente’s text concerning a cycle of five exhibitions on the subject of the narrative, and, of course, there is the “reviews” and the “received books/publications.” Once again, dear readers, you will notice that the essays in this issue’s thematic section have not been translated, as is usually the case. For the benefit of all, we hope that this situation is only temporary.

Translated by Bernard Schütze