Smashing Vases: Ceramics and the Aesthetics of Destruction in Works

by Ai Weiwei and Liu Jianhua

Ceramics are an ideal case study in the aesthetics of destruction. While a ceramic object can be preserved for centuries, it is always haunted by the chance that it might slip from unsteady hands or fall from an exposed shelf. The conceptual resonance of this fragility has long been esteemed in China—a nation so closely tied with ceramics that country and material are synonymous in the Anglophone imagination—and many Chinese artists have adopted ceramics to reveal the destruction inherent to contemporary society. Ai Weiwei and Liu Jianhua are among the most renowned proponents of this aesthetic. From the 1990s to the present, both have used ceramics to expose acts of violence that far exceed a simple smashing of vases, ranging from planned obsolescence, environmental degradation and ecological cycles of decay and renewal, to the redemptive power of destruction as a crucible for regeneration.

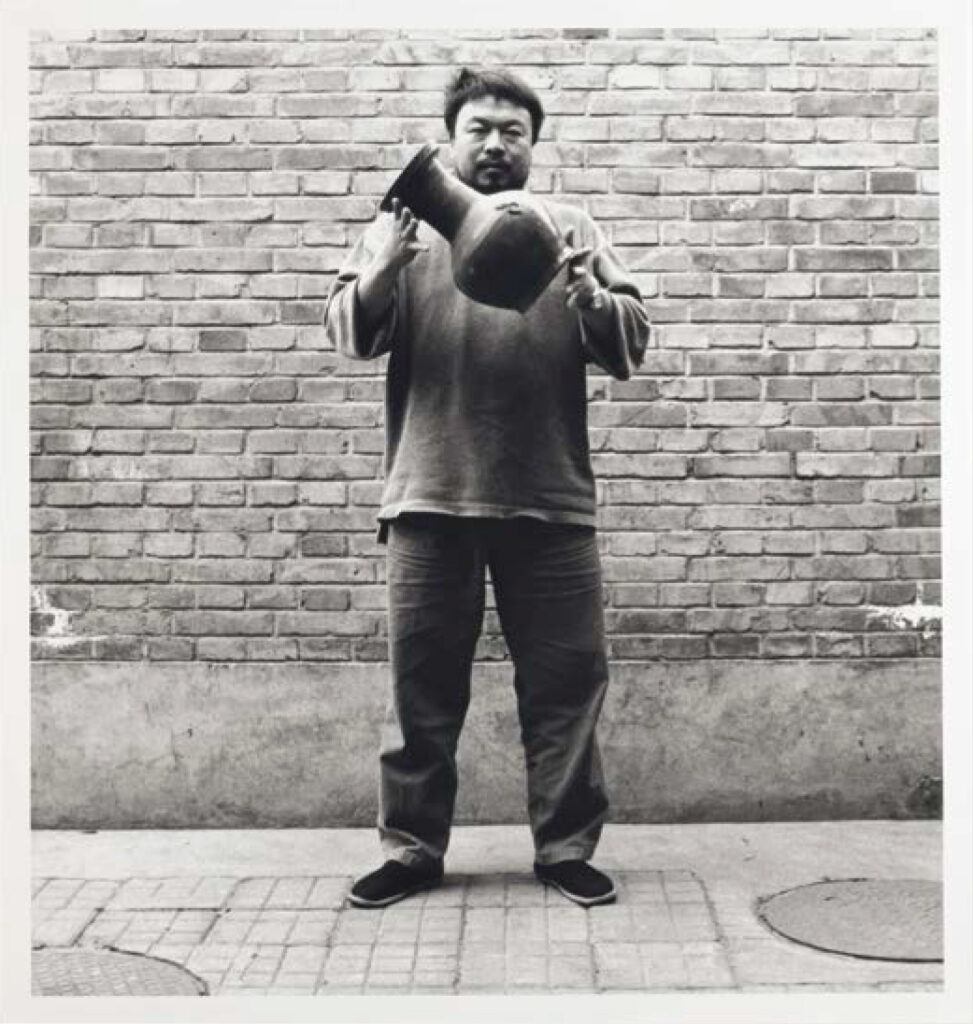

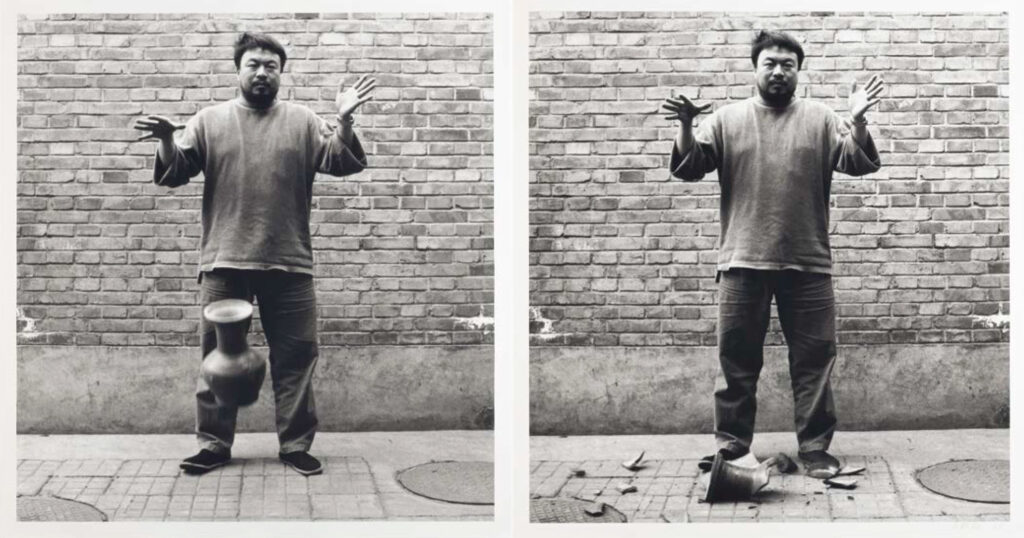

Ai Weiwei’s most iconic ode to destruction is his photographic triptych Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995), usually read as a rejection of China’s past and its contemporary co-option by the state but legible also as a call to revitalise that heritage.1 Destruction is central to this renewal, liberating his appropriated ceramic from the weight of tradition and returning it to a lived existence. By removing the urn from the stasis of a museum case and dropping it to the floor, Ai restores its original identity as an unremarkable wine jar (hu 壶), “the dispensable material culture of [its] time … like mass-produced soda bottles are of ours.”2 The affective impact of this gesture is derived from the fragility of the ceramic medium and restores the vessel to a tangible existence. Defiance of authority could likewise be suggested by dropping an antique bronze or lacquer vessel, but these would not have shattered so dramatically and therefore would not have created the same tension and cathartic release. The term “urn” is also calculated, conjuring antiquarian connotations in contrast to the utilitarianism of the more accurate “wine jar.” These choices of medium and terminology emphasise the image’s complexity as both an iconoclastic gesture and a recognition of the role that destruction can play in ensuring the continued vitality of tradition as a dynamic, evolving heritage rather than an abstract ideal.

A similar ambiguity is apparent in Ai’s Souvenir from Beijing (2002), a deceptively simple work in which China’s urban redevelopment becomes an illustration of destruction’s regenerative capacities. The titular souvenir is a brick salvaged from one of Beijing’s historic courtyard houses, seized and demolished by government authorities to clear ground for new construction, while the ironwood of the box in which it is presented was reclaimed from a Qing-dynasty temple razed for the same reason.3 The humble materiality of unfired clay is central as a metonym for the unpretentious simplicity of the city’s historic buildings and their former occupants—usually those without the socio-economic power needed to prevent their forced eviction—in contrast to the glass-and-steel edifices of the cosmopolitan elite with which they have been replaced. The term “souvenir” is also important as an evocation of memory’s restorative power, imbuing brick and wood with a talismanic significance as aide-mémoires for the rebirth of a disappearing China. As in Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, however, criticism and commemoration are merged. On one hand, Souvenir is a critique of the rapidity and rapacity with which redevelopment is pursued, favouring the desires of the economically privileged over the needs of those forced to endure a more precarious existence. However, in Ai’s words, “China is a nation that needs change … the old part is really rotten and cannot meet contemporary standards.”4 Ai implies that destruction can be purgative, clearing the ground for change, while preservation can be more harmful than beneficial in its removal of the preserved from the fullness of life. Yet his reverent treatment of the abandoned brick is a reminder that the past should not be forgotten, and that demolition must be paired with respect for the destroyed and dispossessed.

In 2003, a year after Ai created Souvenir, Liu Jianhua’s Regular-Fragile (2001-10) installation of mass-produced commodities cast in porcelain was chosen for display at the 50th Venice Biennale, but instead became yet another confirmation of the destructive forces inherent to contemporary life. Liu traces his inspiration for this project to media coverage of plane crashes, recalling that images of passengers’ scattered belongings drove him to realise the fragility of the world of things with which we surround ourselves.5 At the Venice Biennale, he intended to display his porcelain commodities on the walls, suspended from the ceiling, and piled on the floor of the gallery, their warped, sagging forms reminding viewers of our shared vulnerability to disintegration. A further indication of the precariousness of life arose, however, when the show was cancelled following the outbreak of SARS. Two years later, Regular-Fragile was shown at the International Biennial of Contemporary Chinese Art (2005) in Montpellier, France. For this iteration, subtitled Dream, Liu smashed over 6000 porcelain commodities and arranged their shards in the silhouette of US Space Shuttle Columbia, which disintegrated upon re-entry in 2003. In both this and the earlier unintended confirmation of the project’s themes, the threat of destruction lurking in the apparent security of the everyday is brought to light, exposing the extent to which even

the loftiest ambitions can be obliterated in the blink of an eye.

Liu returned to this theme with Discard (2011), an installation of shattered porcelain outside Shanghai’s Sino-Italia Design Exchange Centre that blurred distinctions between landfill and archaeological excavation. For this work, Liu scattered his replica commodities in a cavity of earth and paired them with a mass of broken Ming and Qing Dynasty ceramic reproductions, deposited in an adjacent pool of water. The implication of this is clear: alongside simulated remnants of earlier eras, Liu’s porcelain commodities were imbued with an eerie ethereality, reminding viewers that even those things we consider most contemporary will become relics of a long-forgotten antiquity. At the same time, his excavation’s resemblance to a landfill made the after-effects very clear that the planned obsolescence on which the commodity market depends is collapsing our planet under the strain. As economist Joseph Alois Schumpeter theorised, “creative destruction” is central to the continuity of a capitalist world order driven by our blind pursuit of innovation, “incessantly destroying the old [and] creating [the] new” with little thought to the accumulation of waste.6 The same desire for novelty compels the projects of urban renewal alluded to in Souvenir from Beijing, while also inspiring the fetishism of the past satirised in Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn. In Discard and Dream, Liu exposes the underside of progress, confronting viewers with the realisation that the permanence of past and present are manufactured illusions, and that the only certainty is material dissolution.

A parallel with this revelation of our shared fate can be found in Ai’s Dust to Dust (2009), his most consummate exploration of destruction in the ceramic medium and a potent expression of the cycles of decay that sustain life, as well as the possibility of a desiccation that threatens to destroy it. Like Souvenir from Beijing, this is a deceptively straightforward work: a glass jar filled with clay powder that we are told is the remains of Neolithic ceramics ground to dust. Following the precedent Ai set earlier in his use of the evocative terms “urn” and “souvenir,” Dust to Dust derives much of its intensity from its title, a phrase taken from the liturgy performed at Christian funerals to remind mourners of the impermanence of earthly existence.7 The use of these words to describe the disintegration of ceramics also recalls the action portrayed in Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn: in both works, ossified artefacts are returned to the currents of time through a reassertion of material vulnerability. Yet the irreversibility of these acts could also be read as an Ozymandian warning: a reminder that we, too, if we don’t temper our consumption of the world’s resources, may bring about our end, reducing our global dominion to a handful of dust.

Each of these works shows the suitability of ceramics for an aesthetics of destruction, drawing out the unique qualities of the medium: a tension between endurance and fragility, a connection with natural cycles and an elemental humanity. By smashing, pulverising and enshrining the remnants of ceramic objects and structures, Ai and Liu expose the centrality of destruction to our world order, from the obliteration brought by “progress,” to the environmental degradation wrought by our desire for novelty, to the fragility of the ideological frameworks we create to justify such devastation. More than the physical act of destroying an object, it is the implied dismantling of these frameworks that most clearly expresses the power of an aesthetics of destruction. In Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn and Souvenir, Ai shatters our idealised abstractions of history by exposing the traces of the past within the present, both aides-mémoires and catalysts for change. In his many variations of Regular-Fragile, Liu blurs past, present and future, drawing a forceful comparison between the capitalist rhetoric of progress and the inevitable fact that even the highest ambitions will one day be forgotten and discarded. The final word on the subject, however, falls to Dust to Dust and its reference to the regenerative potential of destruction as harbinger of a new era, in which humanity may or may not play a role, depending on the choices we make now to accelerate or temper our consumption of the world’s resources.

1. For a summary of this reading and a more nuanced interpretation see Dario Gamboni, “Portrait of the Artist as an Iconoclast,” in Gregg Moore and Richard Torchia,Ai Weiwei: Dropping the Urn (Ceramic Works, 5000 BCE – 2010 CE) (Glenside, PA: Arcadia University Gallery, 2010), 86–89.

2. Glenn Adamson, “The Real Thing,” in Gregg Moore and Richard Torchia, Ai Weiwei: Dropping the Urn (Ceramic Works, 5000 BCE – 2010 CE) (Glenside, PA: Arcadia University Gallery, 2010), 52.

3. Urs Meile (ed), Ai Weiwei: Works 2004-2007, 2007, Galerie Urs Meile, Lucerne, 174.

4. Ai Weiwei and Richard Vine, “The Way We Were, the Way We Are,” Art in America 96, no. 6 (July 2008): 100.

5. Yan Yuting and Liu Jianhua, “嬗变中的刘建华: 艺术转变的内在逻辑 – 阎玉婷对话刘建华” [The Evolution of Liu Jianhua: Internal Logic for Art Transformation – Yan Yuting in Dialogue with Liu Jianhua], Eastern Art, no. 3 (2009): 42.

6. Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (London: Allen & Unwin, 1976), 83.

7. The phrase is drawn from an oft-cited passage in The Book of Common Prayer: ‘earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust,’ from Genesis 3:19: ‘In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground; for out of it wast thou taken: for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.’

Alex Burchmore recently completed a PhD in Chinese Art History with the Centre for Art History and Art Theory at the Australian National University, Canberra, tracing the global history of Chinese porcelain and its use by contemporary Chinese artists to explore transcultural visions of the world. He has written for the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, TAASA Review, the journal of the Asian Arts Society of Australia, Art Monthly Australasia and Kunstlicht, and was recently awarded “Best Scholarly Article” in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art for 2018.