Renewing Sculpture’s Possibilities

This second part of the Re-Thinking Sculpture special feature continues the reflection we began in issue 107 on current developments in sculpture, particularly among young artists. In the spring-summer 2014 publication, we examined various aspects related to sculpture and its appearance in what has come to be known, after Rosalind Krauss, as its “expanded field.” We also discussed the medium of sculpture when it is presented in the form of “shadow sculptures.” Finally, sculpture’s possibilities also were considered through the analysis of the works of three artists—Francis Arguin, Chloé Desjardins and Dominic Papillon—who have a sculptural practice. Based on aesthetics of repetition, the aim of the analysis was to evaluate how these artists appropriate the various techniques associated with the history of sculpture1.

In this issue, we once again set out to rethink sculpture by proposing new ways to link sculpture, understood as a medium, with sculptural practices that involve other uses of space. From this perspective, it is hardly surprising that several contributing authors referred to Krauss’ famous 1979 essay in which the art historian mapped the new directions that emerged in the 1960s-1970s2. In analyzing the postmodern sculptural practices of artists Carl Andre, Sol LeWitt, Robert Morris, Bruce Nauman, Richard Serra and several others, Krauss engaged in a reflection on the limits of classical sculpture’s aesthetic language. She envisaged new ways of understanding this medium by analyzing practices in which artists take the exhibition site into account. Consequently, it is not surprising that several of the artists Krauss mentions had participated in Harold Szeeman’s exhibition Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form that was held ten years earlier3.

Today considered a landmark exhibition, this event introduced a new way of rethinking art according to the creative process. Bringing together more than sixty of the most prominent 1960s avant-garde artists, it ushered in contemporary art that was decidedly a break with traditional aesthetics. This legendary exhibition was reconstructed almost identically during the recent Venice biennale4. The curator Germano Celant and his team took over the Ca’ Corner della Regina palace of the Fondazione Prada in order to produce a 1:1 scale reconstruction of the Berne Kunsthalle galleries. This restoration of one of the most important exhibitions of 20th century art history has nothing to do with nostalgia. This “remake” of an exhibition is rather about the challenge of replaying an original scenario so that a new public can have access to it, and to give visitors the opportunity to measure the gap that exists between yesterday and today by way of the exhibition revitalization process.

In parallel to the political context, which was expressed through the “Great Refusal5” during the 1960s and 1970s, the exhibition When Attitudes Become Form, reconstructed or not, anticipates the fluid and shifting presentation of art. An art that emerged through new approaches to potential sites and included actions marked by a rebellious subjectivity unsatisfied with established methods. From this perspective, it was notably about initiating works that were open-ended and in which the process had precedence over the finished product. It was also an occasion to make interventions at the exhibition site, following the procedures of conceptual art, putting performative practices into place or promoting propositions that require an economy of means that is far removed from the materials favoured by the fine arts system. In short, When Attitudes Become Form assembled—in rather tight spaces—“sculptures” freed from the pedestal and the protective barriers that prevented viewers from approaching them. It brought together works, often installed on the ground, which triggered new interactions with the viewer passing through the space.

Without a doubt, these “sculptural” works opened the way for the concept of an installation practice, which has since become a transient notion, but which is still used to designate a work that exists in relation to its surroundings6. Thus, for at least forty years, the vocabulary of sculptural creation has remained confined to this lexicon. Maxime Coulombe’s text, which begins the second part of the special feature section, echoes this problematic. Sculpture or installation, which is one to choose? If numerous contemporary art practices no longer bear any direct relation to the sculpture medium, how does one find the words to designate what we are shown? In her essay, Marie-Hélène Leblanc refers to the works of American artists Ben Jackel and Charles Krafft and Canadian artist Clint Neufeld. Their sculptures, which are linked to the brutality of war, use strategies of diversion to question the masculinity inherent in a certain history of sculpture. Given that sculpture’s original material was in fact stone, how does one “re-weigh sculpture”? How can one “endow emblematically tough and masculine objects with a fragile quality”?

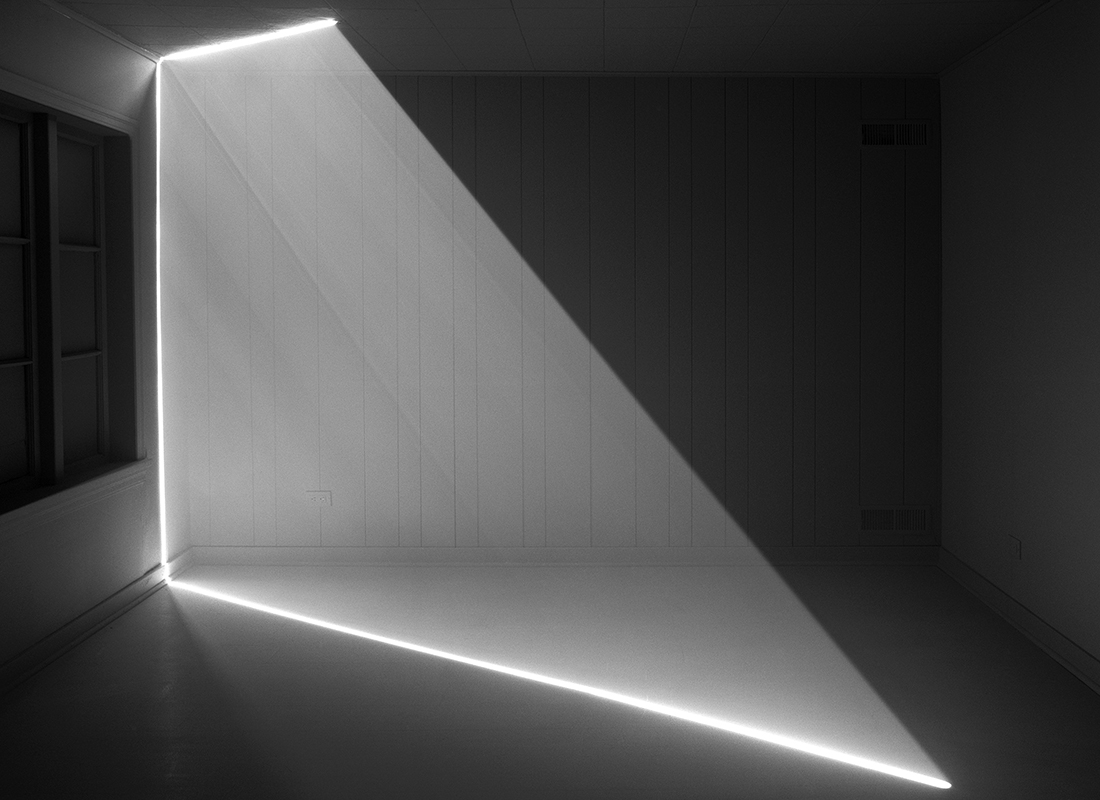

To complete this collection of essays, we invited artists with a sculptural practice to share their thoughts. Peter Dubé interviews James Nizam, a Vancouver-based artist, who discusses his work involving “sculptural images” that are created with a photographic apparatus, making it possible for him to produce light sculptures. And, Montreal artist Guillaume La Brie speaks about his interest in sculpture, more particularly of his preoccupation with the object situated in space. The account focuses notably on his treatment of the exhibition space as sculpture and on how absent objects are presented as forms emptied of their substance.

In the “Public Art and Urban Practices” column, which follows the feature essays, Josianne Poirier reflects on the creation of sound environments in public spaces. Finally, in the “Events” section, Hili Perlson reviews a group exhibition that was held on the fringe of the 5th Marrakech Biennale and showed works that provide various ways of rethinking art as a site of exchange in a social economy that fosters the development of alternative knowledge.

-

Sylvie Coellier, “Sculpture Today: Somewhere Between Enclosure and Expansion”; Claire Kueny, “Beyond Sculpture, the Shadow?”; and André-Louis Paré, “The Possibles of Sculpture,” Espace, no. 107 (Spring-Summer 2014).

-

Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October no. 8, Summer 1979.

-

The exhibition Quand les attitudes deviennent formes took place from March 22 to April 23, 1969, at the Kunsthalle Bern (Switzerland).

-

The exhibition When Attitudes Become Form, Bern 1969/ Venice 2013 was held at the Fondazione Prada’s Ca’ Corner Della Regina from June 1 to November 3. It is featured in a superb catalogue (Ed. Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2013, Eng/Ita.).

-

Herbert Marcuse, “Préface,” Vers la libération, Paris, Éd. de Minuit, 1969.

-

See Patrice Loubier, “L’idée d’installation. Essai sur une constellation précaire,” printed in the first Quebec monograph on installation art, entitled L’installation. Pistes et territoires (directed by Anne Bérubé and Sylvie Cotton) and published by the Centre des arts actuels Skol, Montreal, 1997.