Mathieu Beauséjour, Demi-monde

September 21 –

October 30, 2022

Demi-monde is the intriguing title for Mathieu Beausejour’s recent solo exhibition at Galerie Bradley Ertaskiran. The term, derived from Alexandre Dumas’ 1855 play, refers to a group of women on the margins of society, who receive support from moneyed lovers. Over time, the term has come to refer to what we might now call a sub-culture or a world that is a covert part of the larger world. Considering the underground space where we experience this work, it is a moniker charged with associations from the outset.

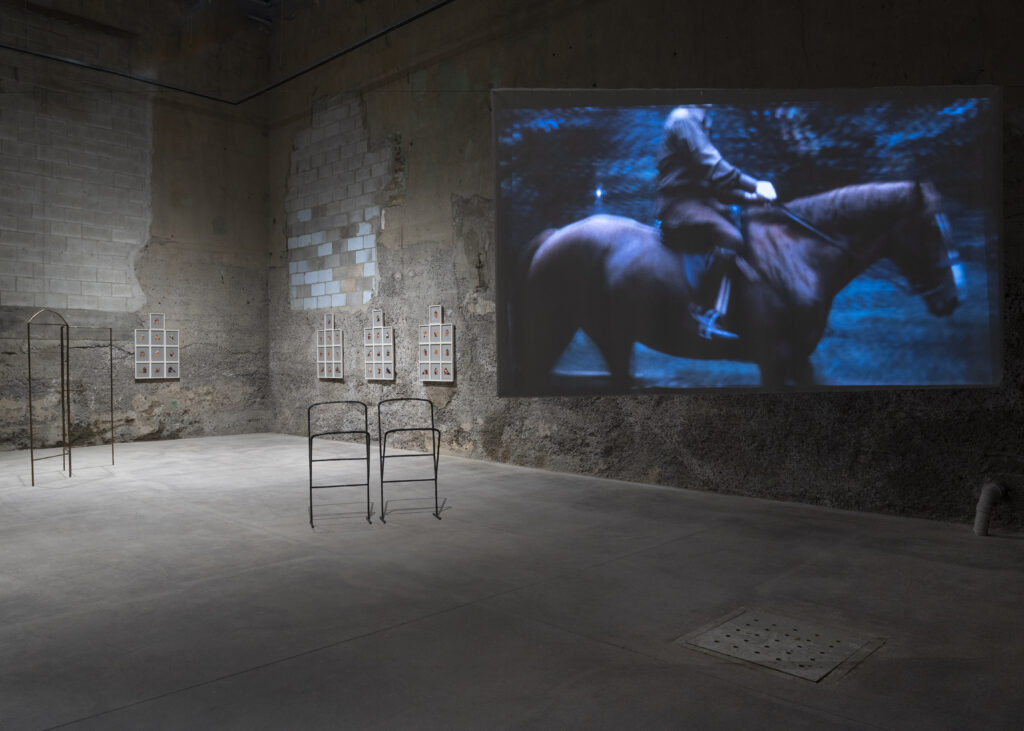

To visit the exhibition from Bradley Ertaskiran’s main first-floor exhibition space we are directed toward “the Bunker,” which acts as the gallery’s second exhibition space. Descending a staircase, we pass through two tight spaces and enter a largish rough-hewn room. The walls are unfinished stone and cement, there are no windows and the dampness indicates we are subterranean. Arriving in the first of two tight spaces, three luscious photo works, Bonsoir I, II and III (2022) welcome us. These appear to be composed of super-imposed body fragments and are mounted on an immense mirror in which we, the viewers, are obviously reflected. In the second, even tighter space, there is a stack of apparently leftover cardboard boxes titled Empilé (2022), many of which contain roughly taped and glue-gunned “interiors” set up within them. An abrupt shift from the seduction of the first three works, this piece is crudely constructed, referring – seemingly – to the netherworld spaces of loading docks or nightclub backrooms. Finally, we enter the main bunker space and are immediately faced with a video projection of Voyeur (2021) on a large sheet of fabric. In the video, young men ride horses repeatedly, while the camera focuses specifically on their boots and buttocks. Behind this projection are two bronze sculptures, one mimics the frame of two folded cinema seats, Le Cinéma (2021) and the other refers to a folded dressing screen, Triptyque (2021). Striking is the absence of upholstery, leaving us with the haunting skeleton-like remains. On the rough walls of the space are two more fleshy-coloured digital prints, La Peau Des Fesses I, II (2022), veering us back to the sensuality that first welcomed us. Finally, four groups of framed paper works, Enveloppe I,II,III,IV (2022) are wall mounted unassumingly at the end of this cul-de-sac space. In all, there are forty of these tiny folded works, each one crafted in a loving or meditative way that upcycles their source material into another realm.

Demi-monde is thus a rather disparate group of works, each one being a complete piece or part of a larger series standing on its own. At first stubbornly independent and occult, we are continuously asked to consider these works together chiefly by their proximity to each other in this rather claustrophobic space. There is no elegant distance here. What gradually emerges is that these artworks are all voices from the past. The Bonsoir, Peau de Fesses and the Enveloppe series are fabricated from material lifted out of 1980s and 1990s gay pornography magazines; Voyeur, from 1970s found film footage; Le Cinéma and Triptyque allude to Deleuze’s classic 1988 text “The Fold; Leibniz and the Baroque;” and Empilé refers to an imaginary past of the artist’s own making. One of the cues for this are the faded, low resolution printed images. Resolutely not of our seamless, high-definition present, they belong to another era. Instead of defining, making clear and contextualizing these images in depth, Beauséjour leaves us with something of an enigma. The artist’s “past” is fading and full of unresolvable tensions. Rather than play the archeologist or historian and overdetermining the work with meaning, the artist gives us a collection of open-ended evocations.

Over the course of a more than twenty-five-year career, Beauséjour’s production has meandered from the openly political, to monk-like meditational drawings, to richly erotic imagery. At each turn, there has been a consistent resistance to norms or typical concepts found in visual art. Instead, he takes many of his cues from literature and music. Like a musician putting together an album or the poet a collection, the artist’s works are full of abrupt shifts and open contradictions, none of which he takes pains to resolve. Beauséjour’s work, through his unwillingness to conform to a singular sense or one direction, by sheer volume of production and largess of reference, has evolved into its own aesthetic. Like David Hammonds or Wolfgang Tillmans, who similarly work on the aesthetic margins of meaning, we are given a result on the periphery of our cultural palette. It can be a frustrating experience until you accept that this endpoint is very much part of the project. We are being disrupted in our smooth pilgrimage towards conventional meaning. Once we accept this, the disruption becomes an aesthetic experience of its own.

Demi-monde is a story of erotic exploration that ends in grief. By the time we begin to connect all the artworks together, we are already implicated and cannot turn back. This is embodied in the film loop Voyeur where we are all witnesses, hence participants in an obsession. Likewise, with the Bonsoir series, the flesh seduces us because we might recognize ourselves in it. If we happen to see the works as erotic, it is the projections of our fantasies that make them so.

This body of work is also a highly personal account of a loss or a gift given then taken back. For the gay community, the post-Stonewall riot 1970s and 1980s were the long-awaited glory days of sexual celebration, liberation and cultural recognition. This time period represented an unburdening from the many confines of the past. Then, gradually, it all seemed to evaporate with the AIDS crisis, the constant re-emergence of conservative politics, surveillance culture and the list goes on. Demi-monde represents a grieving for what, potentially, could have been a better world that instead ended up slipping away into mediocrity. It is a form of lament for a multivalent loss, a failed attempt to say goodbye, and Beauéjour’s most elegiac body of work to date.

David Blatherwick is an artist active since the early nineteen nineties, exhibiting widely in solo and group exhibitions and biennales in Museums, artist-run centres and commercial galleries on a national and international level. He also has many published reviews and publication projects to his credit and his artworks have been the subject of reviews on numerous occasions. He has held full-time teaching positions at the University of Windsor, University of Waterloo and Université du Québec à Montréal. The artist now works peacefully in his studio in the country outside of Montréal.