Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and the Persistence of the Diorama

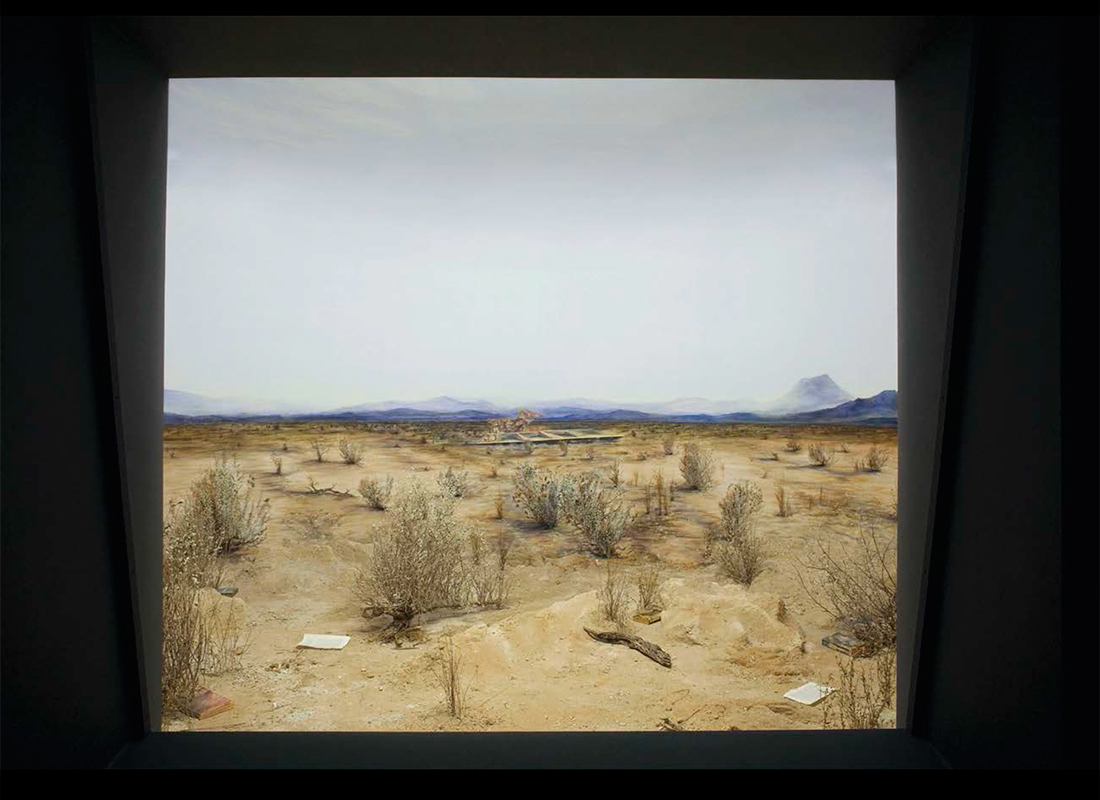

The dioramas that Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster created in New York for the DIA Art Foundation present us with heterogeneous temporalities and places. These display boxes, which are about the size of a small theatre stage, are fascinating because they captivate the gaze and project the body into an intriguing space bathed in light. The models for these works are the dioramas installed in the American Museum of Natural History in New York. They are also a simplified form of the dioramas exhibited in Paris in the architectural complex Daguerre first devised in 1822.1 Many of the Parisian diorama’s technical and formal characteristics remain in the display boxes of the chronotopes & dioramas installation. What is on view in these spaces? Worlds, landscapes, environments in various climates, objects—especially books, because Gonzalez-Foerster created the dioramas in response to a question: “how will books survive or disappear.”2 Disseminated in these spaces, the books are like “beings affected” by “the climate or environment, like all other species.”3 They are living bodies that through their very existence form links with one another.

Gonzalez-Foerster’s viewing devices are also accompanied by a “textorama,” a sort of “literary map” that is displayed on a large wall. This map includes quotes from books that reflect the artist’s literary travels. In the installation context, this approach seeks to incorporate Mikhaïl Bakhtin’s notion of the chronotope and “the intrinsic connectedness of temporal and spatial relationships that are artistically expressed in literature.”4 Chronotopes & dioramas is effectively the title Gonzalez-Foerster used to designate, on the one hand, a 19th century viewing device (the diorama), and on the other, “a literary category of form and content”5 (the chronotope) developed by the author of the Dialogic Imagination essay. The diorama can be etymologically defined as a “viewing through,”6 whereas the chronotope, which can be literally translated as “time-space,” expresses the indissolubility of space and time. If one considers that a “literary work’s artistic unity in relation to an actual reality is defined by its chronotope,”7 it becomes clear why Gonzalez-Foerster questions the relationships of the book with each environment created by the dioramas. It is through a bodily engagement that the viewer can link the “text format,” which is an “endless collage,”8 and the space. The diorama device assists the viewer in this by providing access to “an entropic space for the books and knowledge, a refuge for an endangered species.”9 Through the artist’s reactivation, the diorama is updated in the form of “expanded literature.”10

To appreciate how the diorama can become the medium enabling this “expanded literature,” one must understand its genealogy, particularly by going back to its emergence and reception in the 19th century. In 1877, more than 30 years after the building housing the Daguerre Diorama in Paris burned to the ground,11 Emile de la Bedolière recalls in his memoirs his impressions of “these paintings” as “phenomenal trompe-l’oeil before which one forgot the canvas to believe instead in the reality.”12 The illusion was so powerful that “it seemed possible to wander about the church columns, to climb the rocks, to sail down the rivers, to get to the other side of the tunnels.”13 At the Diorama, it is by “total imitation”14 that an illusion takes shape in the viewer’s eye. For the 19th century public this imitation was an event in itself. One month after its inauguration, Balzac visited the Diorama. In a letter to his sister on August 20, 1822, the novelist considered the invention to be “one of the century’s wonders,” a display that makes it possible to believe that one is “in a church a hundred steps away from everything” even though one is standing before a “stretched canvas.”15 Beyond this initial strong impression, in his novel Father Goriot (1835), he described the diorama as a machine “which carried an optical illusion a degree further than panoramas.”16 Just as with photography and cinema later on, the diorama made an impact through its mimetic power. In the September 25, 1824 edition of Le Corsaire newspaper, a critic discussed the Abbaye de Rosslyn diorama and seems to have been taken in by the illusion when he referred to a painted detail as nature itself, stating that “the sunrays, which appear at intervals, draw shadows on the bodies and the reflection, which fills the interior are so realistic” that the critic believes “for an instant that they were produced by nature.”17 Credulity is the rhetorical form that was hence to set in. In commenting on a diorama, Louis Vitet said “you can not find a piece of wood, a tile, or a stone here that is not as real as it is in nature.”18 The critic expects the viewing device to fool the viewer by making him or her mistake “a copy for an original,” to see “nature” instead of a painting!19 This is also a way of seeing the diorama as a window. The painting opens directly onto nature, like a window, as if the Diorama was the last stage of a long history and theory of painting as an aperture.

Critics favourable to Daguerre also contrasted painting and the diorama, defending the idea that emotion was best served by illusion, captivating viewers with images that stimulate and awaken the senses. For Vitet, the aim of the diorama show was to “trigger an entirely different range of emotions from those typically experienced during a museum visit.”20 Unlike the latter, the diorama would make the viewer “want to walk in the streets and under the archways, to bathe in this river, to climb these rocks.”21 Everything depends on the play of illusion, the credence that is paid to it, and the spectator’s eagerness to be fooled. Louis Vitet clarifies: “everything is lost if you start thinking that there is a painting there in the back, that a painter covered it with colours; the painter has gone to great lengths to make himself invisible.”22 Emotions and their expressions are allowed within the diorama exhibition to the extent that these “old rocks and the moss covering them, this rough ground, these beams, floors and kegs, are all masterpieces of detail that trigger exclamations of surprise and astonishment.”23 The public expresses satisfaction at having access to a mimetic representation and derives pleasure from the illusion that it produces. In this regard, the diorama is welcomed as a medium in which the storytelling power is superior to that of history painting. Henceforth, it is about responding to the public’s expectations and exhibiting contemporary events (such as a landslide or a flood), historical buildings in which events occur in a particular atmosphere (the Midnight Mass at Saint-Etienne-du-Mont) or a remarkable landscape taken from the grandeur of nature. Nevertheless, with an educational aim in mind, the inventors insisted on including a text so that the painting’s contents would be fully revealed. To this end, they copied the Salons’ explanatory pamphlets. The text accompanying the dioramas was based on a visual description and gave an “eye of the beholder” account.24 On one hand, these explanatory texts provided the viewer with support material; on the other, their historical references made it possible to intensify the dramatic unfolding of the image display. The knowledge the text communicated was also a means of guiding the viewer’s gaze. A view Louis Vitet shared, stating in 1826 that in the diorama it is the imagination, which accompanies the gaze through the paintings. The liveliness of the painting is arrived at through knowledge, for “it is no longer solely our gaze, but our imagination that would like to enter these halls.”25

Daguerre is the one who, according to Janin “was seeking something one step beyond painting.”26 The diorama is already beyond painting, because it provides the possibility of “stepping into the paintings’ interior”27 instead of seeing only their surface. To step into the paintings’ interior, as one says of stepping into an image, is a means of projecting oneself into the pictorial and narrative space. This is one of the essential elements of the criticism regarding the diorama technique. Viewers who were drawn into Daguerre’s paintings were promised an experience akin to time travel. Many articles about the invention underline this particularity. For Louis Vitet, contemplating Daguerre’s painted view of the Unterseen village “is to return to this place and experience its big wooden houses and admirable mountains for a second time.” 28

It is in her exploration of the exhibition principles of the pre-cinematic image that Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster discovered the diorama display technique at the American Museum of Natural History. The artist, who has also created a panorama and a nocturama, has effectively integrated the diorama as a medium into her reflections on exhibition display modes. After nearly two centuries, she reiterates the fascination that the combination of luminescence and the perfect illusion elicits in viewers: based on the model of the American Museum of Natural History, her dioramas offer a captivating vision of a recreated world.29 While the diorama’s Parisian predecessor primarily presented an animated painting, the New York dioramas, those of the museum and the ones Gonzalez-Foerster created are not quite made up of an independent image, such as one finds in painting. As the artist states in the text that accompanies the installation, they concern the exhibition rather than the image,30 i.e. they partake of the scenographic object.

The chronotopes & dioramas installation thus explores the contemporary persistence, even the permanence of these spectacular 19th century viewing devices, particularly the Daguerre and Bouton diorama. The illusionistic force, the luminescence emanating from a fictional space, the captivated viewer, the set design that becomes the display itself and, finally, the text as a fictional support of an established program, all contribute to making the diorama one of the peripheral manifestations that make it possible to conceive an alternate genealogy of modernity, and as Gonzalez-Foerster states, to think “about where exhibitionmaking might have gone if cinema hadn’t taken over the function of narrative.”31

Translated by Bernard Schütze

Guillaume Le Gall is a lecturer in contemporary art history at Université de Paris-Sorbonne (Paris IV). In 2002, he defended his thesis on Eugène Atget. He has published books and articles on 19th and 20th century photography and curated exhibitions on contemporary photography, Fabricca dell’immagine, Villa Médicis (Rome), in 2004, Learning Photography, FRAC Haute-Normandie, in 2012, and co-curated exhibitions on Eugène Atget, Eugène Atget, Une rétrospective, Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Paris), in 2007, and on surrealist photography, La Subversion des images, Centre Pompidou (Paris), in 2009. He recently published La Peinture mécanique (éditions Mare & Martin), a book on Daguerre’s diorama.

-

For an in-depth study of the devices of the “-rama” variety, see Erkki Huhtamo, Illusions in Motion, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, 2013. In addition, I invite you to consult my book, La Peinture mécanique. Le diorama de Daguerre, Mare & Martin, Paris, 2013.

-

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, “Preface,” chronotopes & dioramas, New York, DIA Art Foundation, 2010, p. 45.

-

Ibid.

-

Mikhaïl Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, ed. Michael Holquist, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1981, p. 84.

-

Ibid.

-

Diorama – Word Origin & History – Online Etymology Dictionary – Dictionary.com. http://dictionary.reference.com/etymology/diorama

-

Bakhtin, op. cit., p. 243.

-

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, “Frameworks,” chronotopes & dioramas, op. cit., p. 51: “The textorama is the opposite of the dioramas in that it offers the possibility of entering the text, which is an endless collage.”

-

Philippe Vergne, “Preface,” chronotopes & dioramas, op. cit., p. 43.

-

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, op. cit., p. 58: “My growing excitement about the dioramas came from the fact they seemed to offer an interesting way to go deeper into what we could call an expanded literature. I think I’ve found a new way to organize books.”

-

In 1821 Daguerre and Bouton developed the idea of the Diorama. In their business project for a company based on this new form of entertainment, they stated their ambition to “offer a complete illusion through images animated by movements of nature.” (Archives nationales F12 6832 “Projet d’association entre Bouton et Daguerre”). As of April 26, they signed a notarized partnership agreement that founded the project “to establish an exhibition monument of painting effects (visible during the day) under the trade name Diorama.” The Diorama company was founded on January 3, 1822 (For further reading, see: Stephen Pinson, Speculating Daguerre. Art and Enterprise in the Work of L. J. M. Daguerre, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2012). On July 11, they inaugurated the first show in the specially designed building. They presented two paintings: La chapelle de la Trinité, cathédrale de Cantorbery, by Bouton, and La Vallée de Sarnen, by Daguerre.

-

Emile de la Bédolière, “Daguerre,” Les bienfaiteurs de l’humanité, Paris, E. Ducrocq, 1877, p. 340. (Our translation)

-

Ibid. (Our translation)

-

Journal des artistes, 13, 1833, p. 208.

-

Balzac, H. de, Correspondance 1819-1850, t.1, Paris, Calmann Lévy, 1876, p. 68.

-

Balzac, H. de, Father Goriot, New York, The Floating Press 2009, p.76.

-

Le Corsaire, September 25, 1824. (Our translation)

-

Louis Vitet “Diorama, Vue du village d’Unterseen par M. Daguerre – Vue intérieure de l’abbaye de Saint-Vandrille par M. Bouton,” Mélanges, vol. 2, Comptoir des Imprimeurs unis, Paris, 1846, p. 388. (Our translation, in this instance and for all subsequent quotes from this source).

-

Vitet, op. cit., p. 388.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid., p. 390.

-

Notice explicative des tableaux exposés au diorama, s.l., s.d. (1822), p.18.

-

Vitet, op. cit., p. 391.

-

Ibid., p. 145.

-

Ibid.

-

Vitet, op. cit., p. 289.

-

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, op. cit., p. 58: “What I like about the diorama is that, although it shows a frozen world, it engages the body: you see a lot of nose traces on the glass.”

-

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, op. cit., p. 58: “As a mode of display, the diorama is not an image; it’s still in the realm of exhibitions. Since it’s completely sealed, it allows absolutely no interaction other than a visual one, and yet it’s not an image. But because it’s closed, it somehow offers the possibility of approaching it as you do with an object. And, as in any exhibition, you walk around.”

-

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, op. cit., p. 51: “As you know, I am quite into exploring late nineteenth-century categories of pre-cinematic display, such as the panorama, and thinking about where exhibition-making might have gone if cinema hadn’t taken over the function of narrative.”