World of Matter, or Complex Thought about Terrains

When I speak of complexity, I am referring to the primary meaning of the Latin word “complexus,” “that which is woven together.”

-Edgar Morin

While the environmental issue has been and continues to be widely expressed in an alarmist context, many artists now believe that such an urgent matter demands we take the time instead to conscientiously examine our epistemic frameworks of nature. We need only consider Mark Dion’s cabinets of curiosities and other re-envisioned archaisms (Theatrum Mundi: Armarium, 2001), Simon Starling’s co-evolutionary relationships between visual culture, science and nationalism (Black Drop, 2012; Island for Weeds, 2003), Walton Ford’s critical return to the naturalist tradition (Delirium, 2004) and the time capsule that Trevor Paglen sent into the Earth’s orbit for time immemorial (The Last Pictures, 2012). It would seem that by addressing the ecological present from the standpoint of its dense historical memory, these practices moderate the eschatological urgency through an evocative power that Dieter Roelstraete calls an “archaeological imaginary.”1

In addition to demonstrating diachronic depth, the collective project World of Matter’s fieldwork also falls within a range of practices that explore the entanglement of the material environment with human and cultural structures in synchronic and geographically distributed terms. Their research activities weave interrelations between Canada, Bangladesh, Egypt, Liberia, the Netherlands, India, and Burkina Faso, to name just a few, by investigating and analysing the distribution of raw materials. Originally called Supply Lines, the collective subsequently wished to move away from an anthropocentric view of the world and changed its name to World of Matter, which instead evokes the material complexity in which the conditions of human and non-human existence meet and are exchanged.

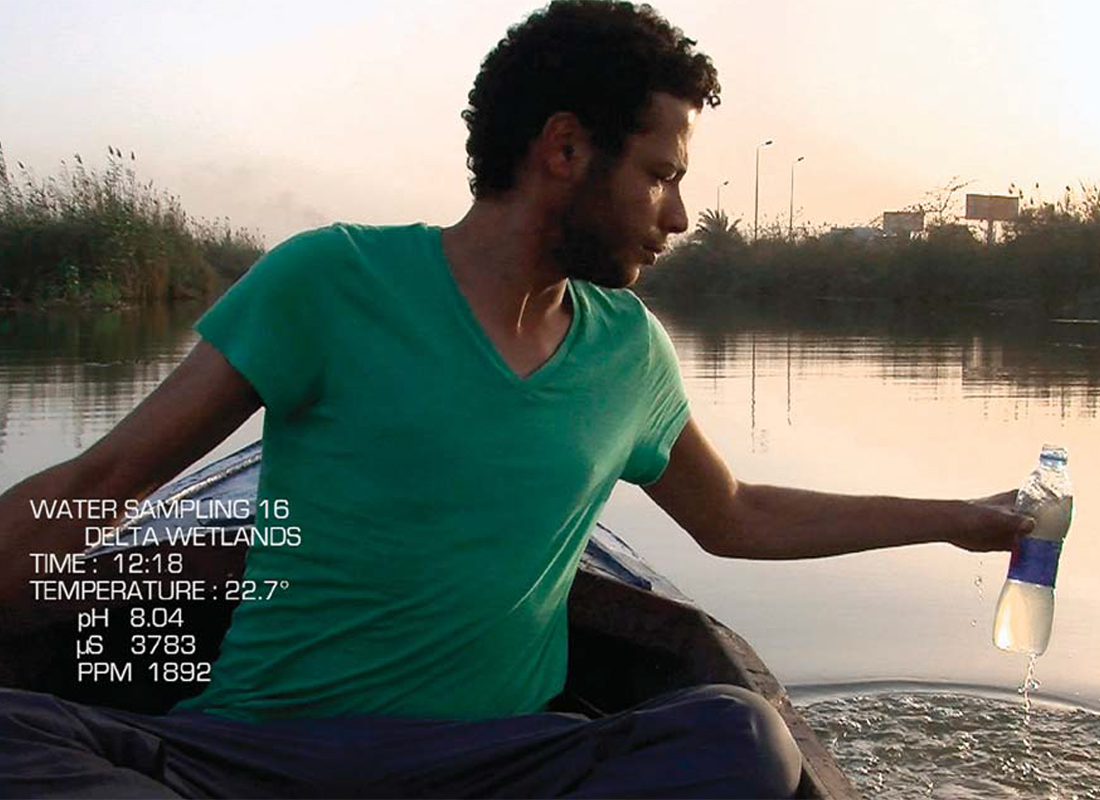

The collective is literally a consortium, composed of ten founding members and four more recent participants—artists, journalists, scholars, and urban planners—whose individual research contributes to the collective platform. Before dissemination, their production has a practical and relational dimension (field research, meetings, discussions, technical considerations, data collection). It then takes a discursive and representational format, using institutional forms of communication such as conferences, round tables, publications, research workshops, and exhibitions.2 The group was formed in 2011 and began disseminating their work in 2013; it thus remains to be seen to what degree they will maintain a coherent vision in the course of their activities. Yet by simply perusing the various projects on their online platform, the relationships are already clearly visible. The myriad of projects assembled on their virtual portal is organized around material resources and their complex and intricate involvement in cultural, political and economic issues. Thus browsing their website, we discover the impact of the production and commercialization of sugar, cotton, water, oil, fish, uranium, wind, arsenic, pastures and soya on populations, conflicts, migration, urban development, borders and life expectancy. All the projects draw on materialist philosophy3 as a tool for understanding and tackling the current environmental quagmire from a different angle. As an example, the World of Matter’s mandate utilizes Latourian terms to re-examine the human kingdom on par with the non-human.4 Likewise, a significant number of projects featured on their platform are based on materialist ontology, such as considering materiality as the basis for lived phenomena, in order to probe the concentration of ecological relationships and the interplay of factors impacting the environment. Such is the case, for example, of Swiss artist Ursula Biemann who turns to Graham Harman’s philosophical thought, in her project Egyptian Chemistry (2012), in order to incorporate the cultural and socio-political development of Egyptian society in a material matrix characterized by the Nile’s hydrological significance.5 This inclination is also reflected in the work of Dutch artists Lonnie van Brummelen and Siebren de Haan, who refer to Latour and Harman in order to examine the European sugar market and the transformation of fisheries in two distinct, though interrelated, projects.

From these various investigations comes an interest in the materiality of the world, its distribution and ramification, in fact their objects of study prove to be closer to what philosopher Timothy Morton calls “hyperobjects,”6 these complex and multiple material entities that have systemic attributes. Referring in particular to climate change and nuclear power, Morton defines hyperobjects as sets of heterogeneous components that interact to produces emergent properties, and in which the implications are experienced disparately in a multiplicity of localities and temporalities. The “objects” World of Matter has tackled, whether watersheds, oil and gas reserves, climate fluctuations, transit systems or transnational industrialisation, eschew any distinct temporal and spatial delimitation and their identity is seen distributed, dispersed and ramified in an immeasurable network of relations. World of Matter thus seeks to espress how matter is transformed, organized in an ever-changing state, and particularly how it fundamentally contributes to anthropic structures (land use, cultural practices, social and political organisation). Although the structured and compartmentalized nature of their talks and publications doesn’t render such complexity very convincingly, the hypertextual aspect of their online portal more effectively enables forays into the network of investigated issues. The projects are first presented as many cells in a beehive, the living components of a perpetually evolving matrix. The site’s overview map then weaves specific and indirect links between the contexts, geographies and temporalities, tracing interrelated narratives between each project’s respective stories. This networked presentation of the collective’s diverse projects emphasizes the intricate nature of political, social, cultural and environmental issues, and the need to tackle them on a common front. The profusion of possible meanings repudiates any dominant narrative, fostering multiple and partial outlooks instead.

Thus, the rather singular history of the Netherlands’ former island of Urk—the subject of the film Episode of the Sea (2014)—echoes situations conveyed in other projects on the website. Urk is the site of a small fishing community that was cut off from its maritime environment, following a large-scale drainage project to increase farmland. Nevertheless, Urk obstinately maintained its maritime activities and insular identity despite its recent integration into the mainland. The film follows the community’s maritime activities in the wake of this and retraces the cycles of cultural, economic and environmental transformation initiated by the artificial construction of the Dutch coastal areas, as well as the ensuing sense of identity. The reclamation of the coast and Urk’s absorption into the artificial province of Flevoland are connected to the farmlands that occupy a large part of the drained land. One of its crops is the sugar beet, described in another project, Monument of Sugar (2007), as the epicentre of complex economic measures and tariff protection against fluctuations in the global market. The European Union’s protectionist stance vis-à-vis its sugar production explains the significant disparity in this commodity’s value between Europe (which protects its markets) and Africa (where Europe disposes of its surplus at the lowest cost). For Monument of Sugar, Lonnie van Brummelen and Siebren de Haan reversed the flow of sugar by purchasing European sugar at a lower price in Nigeria and shipping it back home in the form of a monumental installation—the art work’s legal status allowing it to avoid the duty typically imposed on sugar. Having not been able to find a trace of the European commodity once it arrived in Lagos, the artists had to work sugar shipped from Brazil that was excessively humid and hindered the moulding. Following a conversation with Bruno Latour, the artists agreed that the material’s resistance to being shaped brilliantly emphasized its “thingness,” in which both the ontological and relational scope extends far beyond its use as commodity, stock, merchandise, consumer product and artistic medium.7 The three hundred and four sugar blocks, carefully laid out on the floor in the World of Matter’s exhibitions (and disintegrating more and more with every transport), thus function as a synecdoche of the unstable status of matter when placed in cultural and economic categories. With this kind of interrelation, the World of Matter online portal emphasizes the absence of hierarchy and the porosity and complementarity between projects, which, rather than entailing hermetic objects of study, reveal fragments of a multivalent reality. In a sense, the site is a kind of kaleidoscopic image, glimmering with the myriad facets that make up the complexity of ever-changing matter, which World of Matter strives to reveal through our inter materia exchanges with the living and the non-living.

According to Emily Eliza Scott, “eco-aesthetic” practices and art research platforms are among the most compelling tools for probing this complexity. In an essay on this subject, Scott describes the proliferation of artist-developed research platforms as “an emergent phenomenon wherein self-organized groups probe complex, cross-disciplinary ecological issues and develop structures for sustained investigation, exchange and production of knowledge. These entities not only address (political) ecological matters but also forge ‘ecological’ modes of art-making—based in and on intricate yet durable relations.”8 This is the basis on which World of Matter forms its research identity. Such a willingly variable and indeterminate self-representation is consistent with the spirit of our time, which Brian Holmes has theorized as an “extradisciplinary” form in a special issue of the Multitudes journal, focusing on new forms of institutional critique.9 This extra-disciplinarity stems from an overflow of art, a crossover between various areas of knowledge and an exacerbation of the disciplines’ inherent limits through the clashing of discourses. By remaining on the threshold of art’s institutional framework, World of Matter charts its own path in the wake of materialist thought. The collective’s creolization of disciplinary view points, so as to reconsider them in a more complex relationship with reality, resists any claim to express our being-in-the-world irrespective of materialist contingencies, since, for this collective, human existence is necessarily “formed, deformed and transformed”10 by objects and materials.

Translated by Oana Avasilichioaei

Gentiane Bélanger holds a MFA in Art History from Concordia University and is currently pursuing doctoral studies at Université du Québec à Montréal with support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. Her area of research is at the confluence of art theory and environmental philosophy, and her thesis focuses more specifically on the significance of material culture as a mode for revising ecological discourses in contemporary art. She is a lecturer at the Université de Sherbrooke and Bishop’s University, and sits on the Board and on the programming committee of Centre en art actuel Sporobole.

-

Dieter Roelstraete. “The Way of the Shovel: On the Archeological Imaginary in Art.” e-flux journal 4 (March 2009): http://www.e-flux.com/journal/the-way-of-the-shovel-on-the-archeological-imaginary-in-art/. Web. 4 September 2014.

-

Their work titled World of Matter: Exposing Resource Ecologies was shown at the Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery at Concordia University fron February 20 to April 18, 2015. Extractive Ecologies and Unceded Terrains, a symposium held on February 20 and 21, 2015 accompanied the exhibition.

-

Schools of materialist thought emerging at the moment (speculative realism and object-oriented ontology) redirect philosophical attention towards the extra-human world in its relationship of precedency and surpassing of human consciousness. Quentin Meillassoux’s Après la finitude (2006), in English translation as After Finitude, (2008) initiated debate on the question of the existence and ontological evolution of the material world independent of its apprehension by the human mind. Levi Bryant and Graham Harman placed human thought at the centre of physical processes and exceptionally complex, unstable and diverse webs of objects, thus moving closer to Bruno Latour’s philosophy. The latter critiques the widespread tendency to analyze the social dimension of human existence without taking into account the material context serving as its constitutive matrix. Quentin Meillassoux. After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency. Trans. Ray Brassier. London: Continuum, 2008; Graham Harman. Tool-Being: Heidegger and the Metaphysics of Objects. Chicago: Open Court Publishing, 2002; Levi Bryant. “The Ontic Principle: Outline of an Object-Oriented Ontology.” The Speculative Turn: Continental Materialism and Realism. Ed. Levi Bryant, Nick Srnicek and Graham Harman. Victoria (Australia): re.press, 2011. 261-278; Bruno Latour. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

-

“The social ecologies presented on this site give evidence to the interdependence between human and non-human actants in this fragile system.” http://www.worldofmatter.net/about-project. Web. 4 September 2014.

-

For a comprehensive overview of the collective and its projects, see: Biemann, Ursula, Peter Mörtenböck and Helge Mooshammer. “From Supply Lines to Resource Ecologies.” Spec. issue “Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology” of Third Text 27.1 (2013): 76-94.

-

Timothy Morton. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

-

Lonnie van Brummelen and Siebren de Haan. “Drifting Studio Practice: From Molding Sugar to the Unknown Depths of the Sea.” World of Matter. Ed. Inke Arns. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014.

-

Emily Eliza Scott. “Artists’ Platforms for New Ecologies.” Third Text. http://www.thirdtext.org/domains/thirdtext.com/local/media/images/medium/scott_ee_artists___platforms_cc.pdf. Web. 13 July 2013.

-

Brian Holmes, Stefan Nowotny and Gerald Raunig. “L’extradisciplinaire. Pour une nouvelle critique institutionnelle.” Multitudes Web (2007): 11-17.

-

Bill Brown. “Anarchéologie: Object Worlds & Other Things, Circa Now.” The Way of the Shovel: On the Archaeological Imaginary in Art. Ed. Dieter Roelstraete. Chicago, London: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; University of Chicago Press, 2014, p. 264.