The Call of Excessiveness. On the Works of Jérôme Fortin and Guy Laramée

Guy Laramée, Guan Yin

Galerie d’Art d’Outremont

May 3—27, 2012

The world is large, but in us it is deep as the sea.

–Rainer Maria Rilke

Art sometimes may be created through excessiveness. But how do we measure the “excessive”? How does the work make us see the refusal of limits that it implies? How is this revealed in sculpture when such an investigation strikes up against the inescapable limits of being? How does one make this limitlessness visible, sensual and palpable, when sculpture itself is constrained by, and in, the material that gives it form — here and now? Might the end evoked be that of humanity itself? Can we succeed in conquering this ultimate frontier with an artwork? Sculpture can enlarge our vision: so much so that we may become very small beside it, overwhelmed. Even when we no longer want life’s smallness and we hope with real passion, who wants to yield to boundaries when life tends to expand?

Excessive By Design

“Immensity is within ourselves,” Bachelard reassures us: it spreads in the motionlessness of reverie and dreams, in that solitude that—for a moment—pulls us closer to eternity, and in the silence that is interminable. Interior immensity anchors us in the here and now while sculpture causes images to ripple between the further and the nearer. In this meditative space, the world is no longer perceived as it is but as some other space in which the faraway signals to the distant. Hubris, as defined since the time of the ancient Greeks, testifies to “a refusal of the human condition by denying the boundary that separates mortals from immortals.” 1 It is here, when, as Bachelard puts it so well, “tiny and immense are compatible” 2 that we attempt to bring it closer to us more effectively.

If the works of Jérôme Fortin (Continuum) and Guy Laramée (Guhan Yin) have helped us better understand the workings of excessiveness in sculpture, it is because throughout their practices, each in his own way tends to test the limits even as they take different paths. One borrows from Romanticism and the other from Minimalism; one chooses a more figurative approach, the other a more abstract one. Nonetheless, both their critical points of view and their disturbing gazes reveal a society sworn to forces harmful to humanity—so hungry, so thirsty, and so overtaken by hyper consumption and overcapitalization.

At the same time, the rivalry between the infinite and the finite that excessiveness exposes is developed in arithmetic and geometry, where the duality component of reality is laid bare; just as it is pursued for ethical ends in philosophical and religious contexts. The ambiguity of the limited and limitless physical pair comes up against the equally formidable Apollo and Dionysus. The measured and the excessive have several names, just as they have several histories.3 For the human, in search of some meaning in life, the measured and the excessive are in conflict. Cosmos and logos, man and the gods perpetually fight their ancient combat. The landscapes of heaven and earth remain an eternal battlefield where the powers of the universe are at work, and a place where man’s end is played out. Indissoluble, the duplicity of the world only reflects the duality between hubris and metrion— heaven and earth, shadow and light — clashing on the infinite horizon. The search for life’s meaning, which is never rendered save in totality, is sworn to the “highest forms of hubris,” love, life and death, where everything is suspended and immobile. The union of heaven and earth becomes that of man and the gods.4

Uncertainty in the works of Guy Laramée

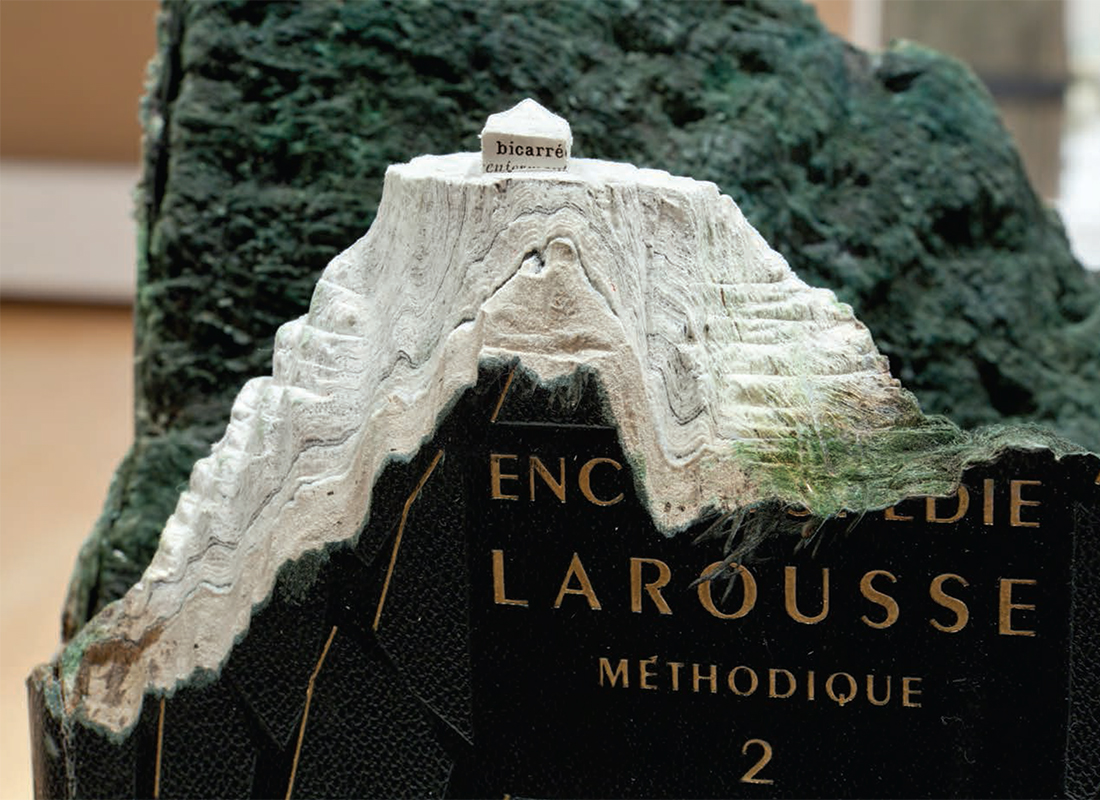

Can we measure the eternally death defying “excessive,” the sacred, which marks even the most fundamental human limits? One must see how Guy Laramée brings forth an entire mountain from a slender slice of a book. Or how in another work, he sculpts a wave like those of Hokusai — perhaps a tsunami — from which the whole sea unfurls. The “immensity in the intimate domain,” 5 as vast as night and day, arises amidst these hyperrealist but vaporous, fog-filled landscape paintings — misty despite their smoothness — and these book-sculptures on whose edges Laramée raises hill and valley, wave and peak. They are vast, take note, not only in the sense of objective geometry but also due to the intimate resonances flowing therefrom. In front of them, we are placed before the immensity of their depth and plunge in, without limit.

There is uncertainty in and before the excessiveness, as if the reason for the book was lost, concealed, removed, eroded by time, ruined by entropy. In fact, as Guy Laramée wrote after the death of his mother, there’s “no certainty,” only an immense silence that unendingly goes on.

“I am certain of nothing,” he adds in the same breath, multiplying the immensity into which we find ourselves projected. A ritual of eternity? And this, despite all the encyclopedic dictionaries, the Biblical bibliographies, thesauruses and compendiums possible, regardless of all the unimaginable amount found, collected, carved, cut out, closed, congealed and taken up by the artist who for a long time has chosen to make the temple of the unknowable. At the heart of this intimate intensity, immensity becomes the consciousness of its expansion, of its deepening. The universe dwindles, shrinks, is concentrated and condensed into uncertainty; this is the “sole conviction left to us,” stresses Laramée, or in other words, it’s the logic of vagueness as it was aptly called by the philosopher, mathematician and semiotician, C.S. Peirce.

Hence his construction of an altar dedicated to Kwan Yin, and before which Laramée spread a carpet of five hundred faded rags sewn together to create a cloth of an excessive scale. The space set up thus predisposes one to be contemplative, the great human value amplifying the immensity evoked. But excessiveness has no object. And yet, lost in thought before the theatricality of Laramée’s sculptures and paintings, we feel our interiority expand. And the expansion happens along with a deepening of intimacy “when the dialectic of self and non-self yields.” 6 Bachelard stresses, “the miniature is one of the resting places of grandeur.” 7 In this game of limits that opens up and moves, the world and the flesh of the world, being and cosmos overlap, whereas it is through their immensity that intimacy and the infinite touch each other and commune on the horizon line. We hope for the growth of the one and the other, in step with the rhythm at which these books are carved, hollowed out and taken apart to create minute landscapes: tiny, small, perched on the edge.

The Unattainable

There are no beautiful surfaces without a terrible depth.

-Nietzsche

How does the “excessive” appear in sculpture when such an investigation strikes up against the inescapable limits of being? Artists have understood this. Some have expressed it with a simple line as in Brancusi’s Endless Column, Christo’s Running Fence, Carl Andre’s Lever, Richard Long’s A Line Made by Walking and others — closer to us — such as Jérôme Fortin have produced Continuum, a tribute to American composer Morton Feldman. Open cardboard boxes filled with metal openwork bits, the tops of ordinary cans meticulously cut, the patterns rigorously calculated, juxtaposed and aligned one to the other to form a modulating line that stretches out, lengthens, grows more vast, is superimposed, continues on, unfolds and unwinds, tracing an imposing trajectory pumped up with all its serrations and cut-outs, its scooping-out and grooves repeated. All reiterated over and over, a thousand times rather than once, to the point at which they endlessly recreate an immense flux, containing its incalculable reflux, seeking to go further still, lengthening and extending endlessly. But so many little holes and openings, so many blank spaces and cut-up days open up the inner spaces, marked by the “track made by the moving point,” that “invisible thing” wrote Kandinsky, and which “in the flow of speech […] symbolizes interruption, non-existence (negative element) and at the same time it forms a bridge from one existence to another (positive element)… In writing, this constitutes its inner significance.” 8 For Kandinksy “the geometric point, has therefore, been given its material form in the first instance, in writing. It belongs to language and signifies silence.” 9 And the line, “the archetype of limitless movement” carries “the most concise form of the potentiality for endless movement.” 10 Jérôme Fortin takes great care to punctuate this in order to create silence and divert us from an over-embellished line and to provide a supplemental area for intimate being. Each day engenders a new space for silence or speech, for breathing or breath, a breath that becomes the breath of life itself, of the universe; that tears us from the tribulations of historical time—even the end of time, and the end of the human being.

The Endless Call

Sublime… the absolute removal of

the limitless from all limits.

—Jean-Luc Nancy

Are we to be haunted by this presentiment of the world’s limitlessness —reflected in man, by “this cosmic obsession that devours us” 11 of which Cezanne spoke? The scope of this created world engenders another space, a sacred zone as is indicated by the etymology of the term, sacer that refers to the “other share,” evoking less what one might make sacred than what is sacrificed and dissolved, returned to nothingness.12 This other “distribution of the sensible” 13 to which this excessiveness summons us and which is distinct from the common sense specific to a particular age, expands consciousness, which dilates and seems limitless, without end.

The flow of impulse and the pressures of reason clash, and clash in us. Measurement dominates the game of proportion and balance, while excessiveness undoes them and interrogates this temporary and partial accident of limits. Sacredness and sacrifice blend in that paradoxical space. Nothing of the minute and the colossal appear without at the same time unveiling a past and a future, projecting them into a night and a dawn with the power to slip off the eschatological time of history and gods. We are disoriented in the midst of the miniatures, as we are in the complexities of the excessive, too vast when everything shifts and jostles in all directions, from North to South and East to West. The search for excessiveness strikes up against the inescapable limits of being. Bit by bit, death and the sacred mark out the most fundamental human limits, those that challenge our existence. A sublime moment? Very likely.

Translated by Peter Dubé

Manon Regimbald, Ph.D. is an associate professor in the art history department at UQAM and Director of Centre d’exposition de Val-David. A member of the Groupe de Recherche en Éducation Muséale, she has organized many exhibitions and published numerous texts on interdisciplinary topics. Concerned with landscape art and gardens, she is also interested in the problematics of space as well as the overlapping of text and image.

-

Jean-François Mattei, Le sens de la démesure, Monts, Sulliver, 2009, p. 29. (Translation mine.)

-

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, (Maria Jolas, trans.), Boston: Beacon Press, 1964, p. 172.

-

François Flahault, Le crépuscule de Prométhée. Contribution à une histoire de la démesure humaine, France, Mille et une nuits Fayard, 2008.

-

Jean-François Mattei, op. cit., p.174.

-

Gaston Bachelard, op. cit., p. 193.

-

Gaston Bachelard, op. cit., p. 173. (Translation mine.)

-

Gaston Bachelard, op. cit., p.159. (Translation mine.)

-

Wassily Kandinsky, Point and Line to Plane, New York: Dover Publications, 1979, p. 25.

-

Ibid., p. 25.

-

Wassily Kandinsky, op. cit.,p. 57.

-

Joachim Gasquet, Cézanne – La Versanne: Encre marine, 2002, p. 235. (Translation mine.)

-

Pierre Ouellet, Où suis-je ? Paroles des Égarés, Montréal, VLB éditeur, 2010.

-

Jacques Ranciere, Politics of Aesthetics, New York: Continuum, 2006, (Gabriel Rockhill, trans.)