Art and Psychoactives

On behalf of public health, the Canadian Parliament is preparing to legalize the recreational use of cannabis. By regulating its production and consumption, and no longer prohibiting it, Canada makes this drug a very lucrative substance like tobacco and alcohol. Instead of punishment and prosecution, the government has chosen to oversee its use and provide education on its potential risks. And it is the dangers harboured by this psychotrope that the government aims to counter in order to protect the most vulnerable. While it is true that the Western countries have cared for public health since the start of the industrial revolution, when it comes to the consumption of cannabis it is only recently that a few have chosen the path towards legalization. The politico-medical surveillance of its use is maybe justified in the name of the public good, but it goes without saying that despite this impulse to control, individuals will always find a way around it. With the proliferation of party drugs and other legal euphorians, the overprescription of medication, and, of course, the illegal sale of drugs through organized crime, the fight against the growing presence of psychoactive substances towards social normalization and disciplinary control is long from being won. And what about in the field of art? What links do artistic practices have with psychotropic substances?

Drugs, long found in nature, were inherent to the habits and customs of the oldest of human societies, and were used to produce hallucinogenic experiences in the context of sacred rituals or to benefit from their medicinal qualities. In the West, it has been primarily scientists and artists who are interested in these substances, exploring their effects on consciousness and our relationship with reality. Yet, little by little during the 20th century, the proliferation of drugs has changed, distancing us from a consumption linked to spiritual pursuits. The desire for transcendence has given way to a need to intensify the trip, the illusion of escaping reality. Also, the consumption of a diverse range of increasingly mixed and synthetic drugs has grown in popularity since the psychedelic era. It was also in the 1960s that this became a recurrent theme in cinema, often presented under its deadlier aspect with figures of the junkie, the drug addict, or in reference to writers and musicians for whom abusive use of illicit products contributed to their creative defeat. Finally, due to increasingly sophisticated cinematographic techniques, the 7th art has made the effects of drugs on perception and the imagination visible on the screen, frequently in a wild fashion. And, what about drugs in the hands of visual artists?

In 2013, Sous influences, arts plastiques et produits psychotropes (Under the Influence: Art and Psychotropic Substances), an exhibition at La Maison rouge in Paris, assembled a more or less exhaustive panorama of works by ninety artists, concerning this relationship between the visual arts and psychotropics. The curator, Antoine Perpère, favoured mainly works having to do with the formal representation of these substances as well as those that artists produced while under the influence of psychoactive drugs during creative research. Camille Paulhan, in her text in this issue, refers to a number of artists who were presented in this exhibition. Concentrating on the recent history of psilocybe in art, she hones in on artists’ contributions depicting the universe of hallucinogenic mushrooms on canvas or in sculpture. Also in this exhibition were Bryan Lewis Saunders’ self-portraits produced under the influence. His rather unique practice of drawing his face following the ingestion of medications or illicit drugs is the object of François Lachance-Provençal’s fine analysis in which the artist’s absorption of drugs is but one way of transforming his psychosensorial rapport with the world.

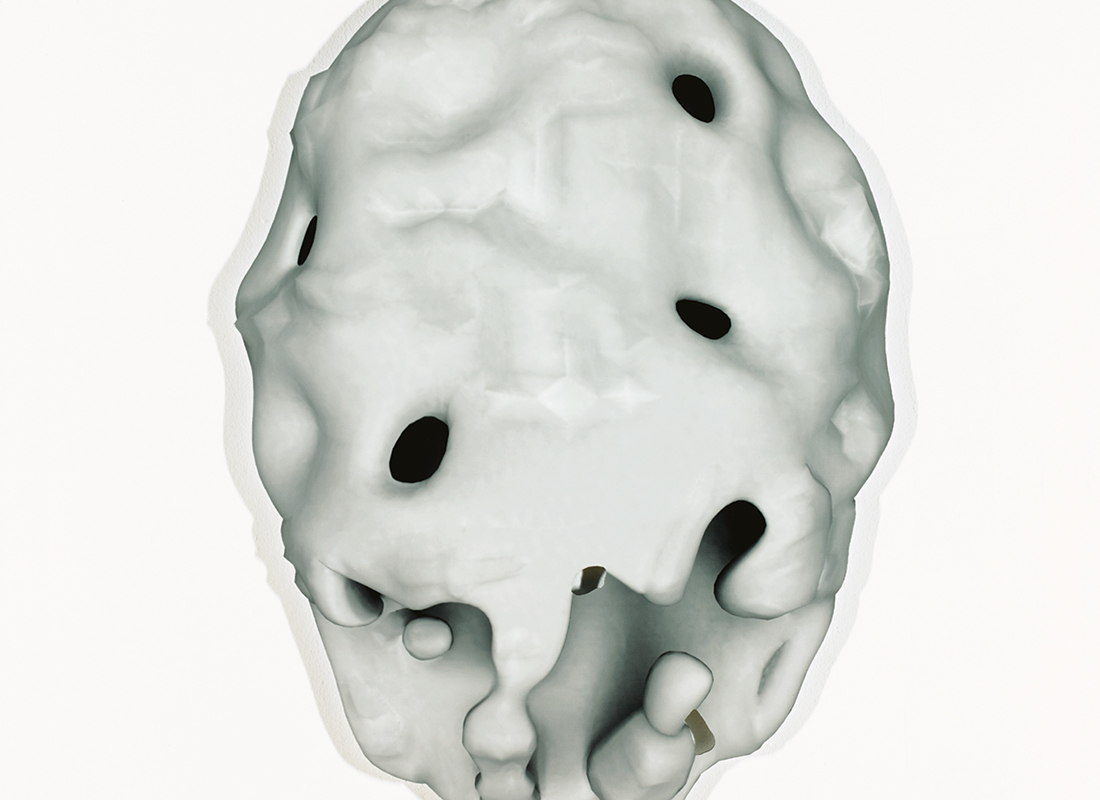

In the spring of 2018, Altered States: Substances in Contemporary Art, an exhibition at KunstPalais (Erlangen) also underlined artists’ contributions toward visualizing the effects of an altered consciousness, among these artists were Canadians Rodney Graham and Jeremy Shaw. Graham’s Phonokinétoscope (2001) is a film in which we see the artist in a park in Berlin in the process on ingesting LSD to a backdrop of pop rock music. For his part, Shaw presented the video DMT (2004). In this issue, Mathieu Teasdale proposes an interesting interpretation of this experiential work involving Shaw and a few friends. DMT is a powerful hallucinogen found in certain compositions used for shamanistic ends. As with the video works Quickeners (2014) and Liminals (2017), the artist is interested foremost in the capacity of an altered consciousness to sublimate reality, to represent ecstasy, and produce that unexpected moment where the psyche intrudes in another mental space. Also in modifying our states of consciousness, today we are able to visualize the physical consequences on the brain. Accordingly, in Degenerative Imaging (2015) Shaw shows the degenerative effects of psychotropic substance use on the blood flow and metabolism of the human brain.

As this issue’s co-editor Bernard Schütze reminds us, drugs have always been considered a phamarkon—a substance that heals or poisons. In the current conjuncture, the sale of drugs is an integral part of global capitalism and its attendant pharmaceutical industry. In his text, Schütze dwells on select works of artists Beverly Fishman and Sarah Schönfeld. Fishman, in her works, reflects on the marketing of increasingly alluring medication, while Schönfeld presents the effects of certain drugs once placed on photographic film. Like Fishman, Collen Wolstenholme uses the form of commercial pills to create installations as well as jewelry. In his text, Ray Cronin analyzes the works of this artist from a feminist perspective and her resistance to the massive pharmaceutical industry, regarding the control of our emotions. This affective control is also the subject of artists Richard Ibghy and Marilou Lemmens’ video work Visions of a Sleepless World (2014-2015). Michael DiRisio analyzes this work in which it is a question of medication that stimulates alertness in the context of a productivity that is always demanding increased performance.

As we know, this intrusion in the medication market has crossed the line into what must be called “The Opioid Crisis.” Whether in Canada or the United States, the consumption of painkillers such as the prescription opioid OxyContin has killed thousands by overdose. In her text, Suzie Oppenheimer reminds us of Nan Goldin’s fight to break her dependence after she was prescribed this “medication” to treat tendonitis. She is now fighting the drug’s manufacturer, Purdue Parma and holds the Sackler family responsible, having made a fortune in the marketing of this product. To add to the irony, the Sackler family use this fortune to support numerous museums. In short, the relation between art and psychotropes in light of the polico-medical situation gives rise to various points of view. This can be the desire to capture personal universes of rare intensity or contribute towards taking a stand and denouncing its omnipresence in a society devoted to a cult of health and fitness.

In addition to the collection of essays, this fall 2018 issue takes a look at two major events: the brand-new biennial in Riga and From Africa to the Americas: Face-to-Face Picasso, Past and Present and Here We Are Here: Black Canadian Contemporary Art an exhibition at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. As well, in the “Essay” section, you will find a text on Danish artist Christian Skjødt’s sound installations. And, as usual, the exhibition and book reviews sections have some great discoveries.

Translated by Robin Simpson