Aram Han Sifuentes: The Politics of an Immigrant

Aram Han Sifuentes is a fibre artist with a social practice who works closely with Chicago non-profit organizations, community centres, and public schools to facilitate workshops for immigrant communities. She has exhibited her work nationally and internationally. Her solo exhibitions include A Mend at Hollister Gallery in Wellesley, MA, and 73,000 waiting at Chicago Artists Coalition in Chicago, IL in October 2015. She has given workshops such as Immigrant Takeover at the Center for Craft, Creativity and Design in Ashville, NC, and US Citizenship Test Sampler at the Smithsonian Institution. A DCASE grant and Puffin Foundation Ltd grant recipient, Han earned her BA in Art and Latin American Studies from the University of California, Berkeley in 2008, and her MFA in Fiber and Material Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2013. She is currently a lecturer at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

You were in residence at Est-Nord-Est in Saint-Jean-Port-Joli (Quebec) in the spring of 2014. This was an opportunity for you to continue your work entitled US Citizenship Test Sampler: tell us what is this project about?

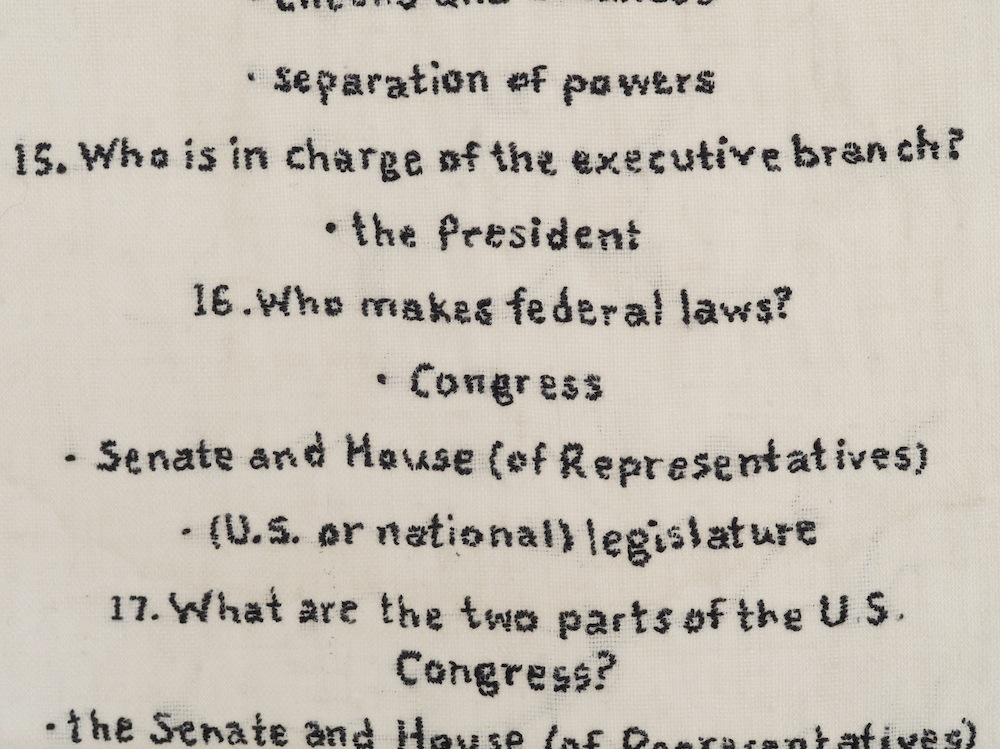

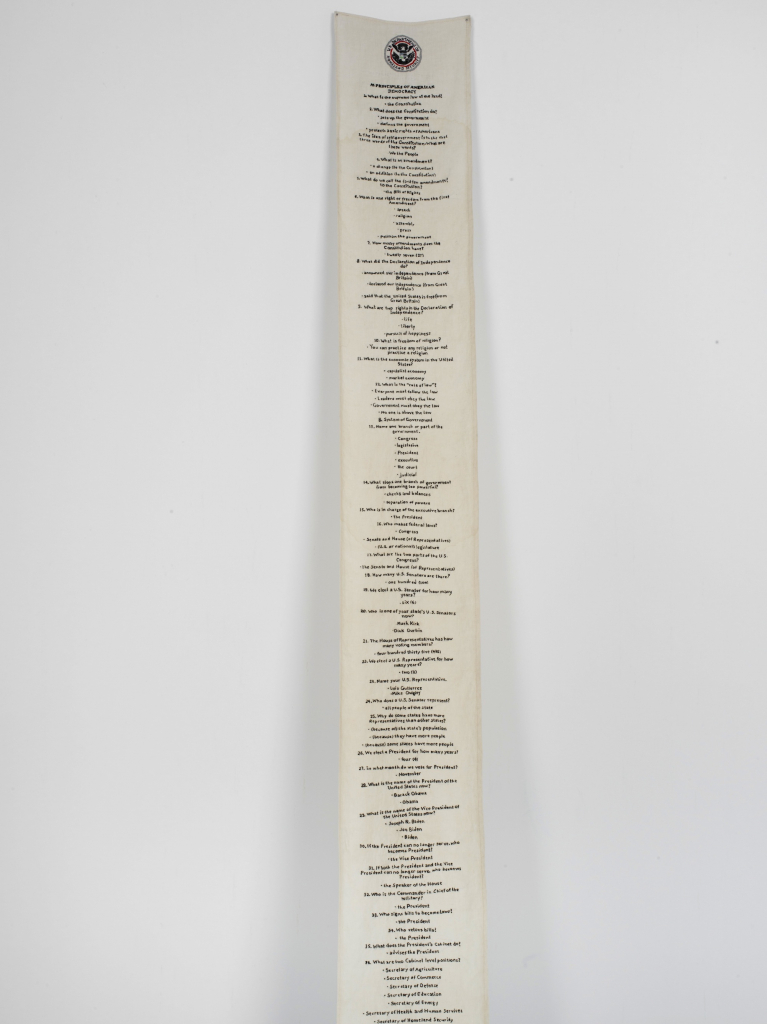

Aram Han Sifuentes : I’m currently hand-sewing the 100 civics study questions and answers for the US Citizenship Test. I got the idea for this project while I was reading about the history of traditional American Needlework samplers. In colonial America, schoolteachers used samplers to teach young children how to sew. The children would stitch the numbers and the alphabet, which then also taught them basic educational concepts. In addition, girls who were able to continue their education would make another sampler in their adolescent years. This sampler was more decorative and pictorial, and would signify her value as a wife to her potential suitors.

I’m not a U.S. citizen, even though I’ve been living in the United States for over twenty years. Recently, I decided that I want to become a citizen. But this process isn’t that easy. I have to study 100 civic questions and answers for the Naturalization Test. So I decided to appropriate the language of Traditional Colonial Samplers to create my own U.S. Citizenship Test Sampler. Like traditional samplers, I’m using the process of sewing as an educational tool. In addition, I am selling my completed sampler for $680–the cost of applying for naturalization. I’ll only get my citizenship if the work sells, and thus I’m letting others decide if I’m worthy of becoming a citizen.

I’m also recording the hours that I work on the sampler. Currently, I’m on question number 53 and have put in over 250 hours. That makes it less than $3 an hour. I estimate that upon completion, the cost of my labour will be less than $1 per hour. This for me, highlights how our society undervalues manual and immigrant labour.

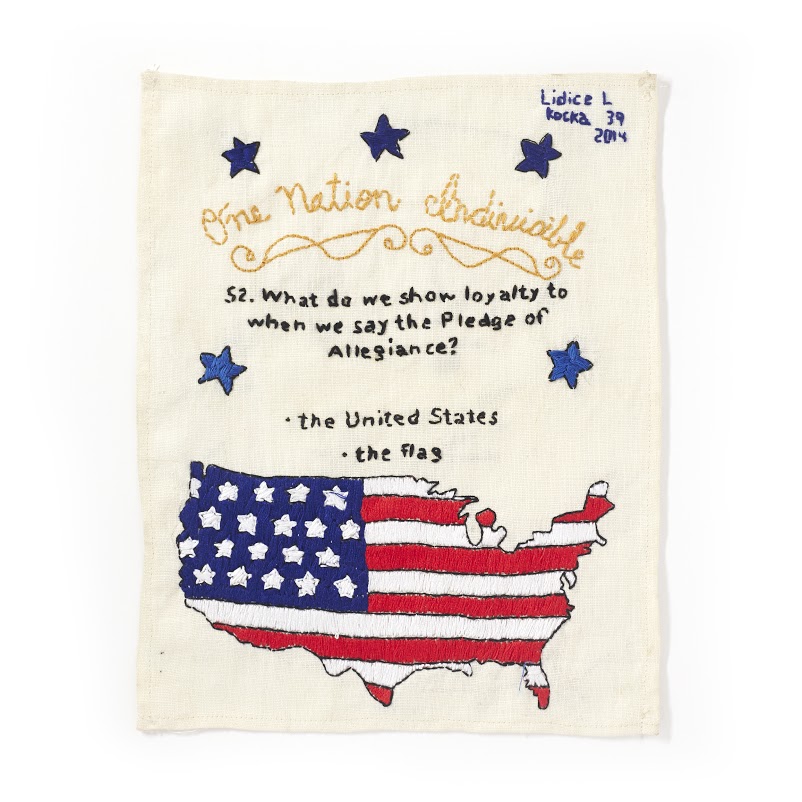

At the core of this project, I’ve been facilitating a series of citizenship workshops in Chicago, IL and Oakland, CA where communities of non-citizen immigrants come together to learn the citizenship test material through the act of sewing their own samplers. Also each of the samplers is sold for $680, with the full amount going to the sampler maker. Each workshop member embroiders one question and answer, and nearly 90 unique samplers are now part of the project.

Most importantly, the sampler workshops organically become grassroots round-table discussions, addressing immigrant rights, labour politics, and everyday concerns of intergenerational and multiethnic migrants. The results of this project are a living archive of these people and their experiences, providing resources and information. So, I use samplers to engage with the social and collective nature of needlework’s history, as well as to exhibit the value of non-citizen communities.

You use needles to inscribe the 100 questions of the citizenship test. Why do you work with your hands rather than using a sewing machine?

Well, the fact that hands are used to make these projects is, in reality, the most important aspect of this project. Its significance is twofold. First, the hand represents humanity in the labour process. It marks the time, sweat, and blood in the labour histories and practices in the U.S. and across the globe. Second, it recalls the history of samplers in which the value placed on the individual was based on the skill of their hands.

When working by hand, many more things are involved, which would not be the case if one worked on a sewing machine. For instance, the sense of touch is more activated, and the process thus becomes more intimate. To sew, the hand, armed with a needle, pierces the cloth, pulls the needle up, pierces the cloth, and pulls the needle down. Each sewn thread creates an indexical line of invested time, gesture, and rhythm. This is important to me and to the people that I interact with in this community-based project. We use our hands to create our samplers. The hand, in its slowness is what gives us the time to share our experiences with one another, and to reflect on our current situation as non-citizens. Thus with our hands, we instill our thoughts and politics into each sampler.

For me, the needle is a political tool. It pierces and binds membranes together. The thread that it steers is tied off and remains while the needle continues to bind and mend. In my art practice, I use the needle to stitch together various histories and discourses, revolving around the simple act of sewing. However, this act is anything but uncomplicated. The creation of each stitch engages sewing’s complex histories and the politics of traditional, industrial, feminist, immigrant and artist labour.

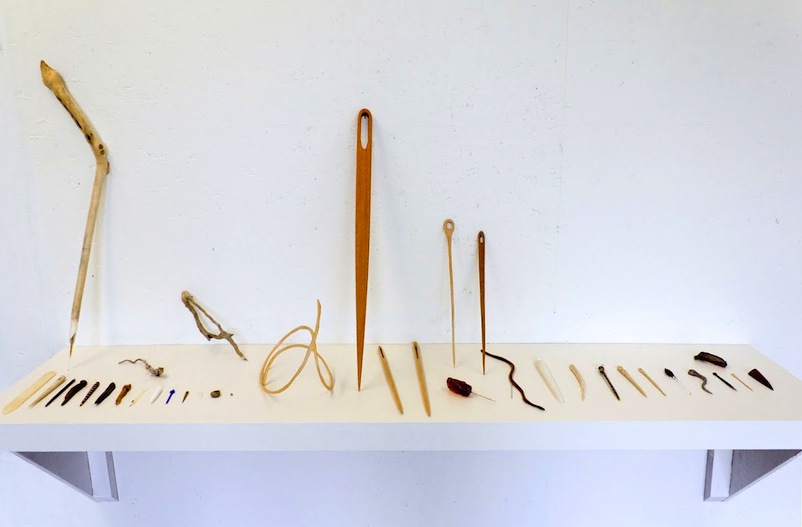

During your residence in Saint-Jean-Port-Joli, you also asked artists and artisans to make needles…

I left Chicago with only a carry-on bag. To avoid any conflict with TSA, I left behind my fundamental tool for art making: a needle. I was interested in the challenge that I created for myself. I had to construct needles out of what I could find in my everyday environment in Saint-Jean-Port-Joli as a resident artist at Est-Nord-Est. I took the bus into town and saw the main road crowded with artisan studios and shops. At that moment, I decided to ask this community to help me in my endeavour to create handmade needles.

The artists and artisans were free to choose the material, size and shape of the needle. I only asked them to make it functional. And each needle-maker interpreted “functionality” in his/her own way. Many of them made decisions based on practicality and utility, while other artists and artisans created nearly non-functional needles with a sense of humour, knowing that I would have to drastically alter my way of working in order to adapt and accommodate each needle’s characteristics. For example, artist Pierre Bourgault wanted to playfully test my skills as a sewer by making me a curved needle shaped like a roller coaster.

The act of commissioning needles was a mere catalyst for engaging in a conversation about manual labour. The artisans and artists’ hands skilfully crafted an object that was then passed into my hand for use; every decision that they made in creating the tool was felt in my hand and became evident in each stitch.

Besides allowing you during your residency to forge links with the artists and artisans from this part of the country, the needle, as you mention elsewhere, is also a political tool for you. In your artistic career, it is linked to immigrant workers. This was the case for a work entitled A Mend: A Collection of Scraps from Local Seamstresses and Tailors.

Definitely. At the core of my practice I am a collector and researcher. I collect material such as oral histories from various people, commission artefacts from artists and artisans, and save remnants of immigrant handwork. The act of collecting becomes the true spirit of the work. The process of collecting materials becomes a catalyst for conversation.

A Mend: A Collection of Scraps from Local Seamstresses and Tailors was the first project in which I collected material from a community of people. I was interested in seamstresses and tailors because my mother, who used to be an artist and arts educator in Korea, is now working as a seamstress at my parents’ dry cleaners. I was curious to find out how others come to do this type of labour. So I went around the city of Chicago, looking for all the seamstresses and tailors I could find. I visited 23 people and I was surprised to find that all of them were immigrants. I asked them to donate their jean cuff remnants because hemming jeans is often the bulk of their work. While collecting this material, I asked them the following questions: How long have you been in the US? How long have you worked as a seamstress or tailor? What type of work did you do before in your country of origin? How much do you charge to hem a pair of jeans? While answering, many of them shared their personal stories, which I’m currently compiling into a book.

I met so many generous and wonderful people with this project and I’m still in touch with a handful of these seamstresses and tailors. What I learned from all the conversations I had was the difficult reality of immigrant labour. Immigrants confront systemic discrimination, since they cannot pursue various occupations even if they have the experience, qualifications, and credentials from their countries of origin. Some of these seamstresses and tailors used to be nurses, schoolteachers, graphic designers, businesswomen and men, artists and so on. Usually, because many immigrants do not speak English, their employment options are limited. Many of them end up getting jobs that pay low wages, require repetitive manual labour, and are sometimes hazardous, having no union or collective bargaining protection. This is the case for seamstresses and tailors who perform piecework or sweatshop labour, which requires them to work long, tedious hours for low wages, and often at places where work is unregulated or even to take extra work home.

Like many other migrant artists you focus on the theme of immigration. What do you think is special about your work compared to other artists’ practices?

I came to the United States from South Korea when I was 5 years old. My family moved to Modesto, California, in the Central Valley, which consists mostly of farming and agriculture. There is a huge population of migrant farm workers in Modesto and the town’s population is now over 50% Latino. So I grew up in a city of immigrants. From there I went to the University of California, Berkeley for my undergraduate degree. I studied Latin American Studies and focused mainly on immigration policy. A month before I graduated I decided to pursue art. And it was only a few years ago that themes of immigration became part of my art practice. So, I find my background to be unique. However, I don’t think that my work is unique per say. I find that it’s part of something bigger, politically and aesthetically, in which artists use their work to confront social injustices.

Finally, which artists do you admire whose work deals with immigration? Which immigrant artists do you admire?

Of course I love the works of Kimsooja, Do Ho Suh, Tania Bruguera and Michael Rakowitz who make work about dislocation and the immigrant body.

I just recently gave an artist talk and did a workshop for the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art in conjunction with their exhibition on the work of artist Yasuo Kuniyoshi. He deals with themes of citizenship and immigration in his paintings, but I am more inspired by his life story. He was a Japanese-born American artist who lived during the first half of the 20th century and was regarded as one of the most esteemed American artists of his time. He came to the United States when he was sixteen years old and right away started to paint. During WWII, he was classified as an “enemy alien” and had to prove his loyalty to the United States. He even worked with the Office of War Information to create propaganda posters indicting Japanese atrocities. In 1952, he finally became eligible to apply for citizenship; however, he died in 1953, never able to become an American.

When I was in Montreal last summer, I went to the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal and was blown away by Angelica Mesiti’s Citizens Band video installation. In this work, she films four immigrant musicians who perform their art in everyday public places, such as the metro and inside a taxi, which one of them drives for a living. I was completely floored by this installation. We often disregard the lives that immigrants had before they enter a new country. For me, this work highlights the culture and life immigrants bring with them to a new country.