Laboratory thinking

Unless you are Robinson on his desert island, the arrival of Covid-19 and the current public health crisis along with the ensuing debate, notably on its origins, has reminded us of an obvious fact that we at times have a tendency to underestimate: we live in a world in which our everyday realities are ultimately all interconnected. Although recent history of the past century has already confronted us with events that repeatedly test our resiliency, we have never—thanks in particular to telecommunications and social media—shared a situation that has given us the distinct impression that we are all “in the same boat.” In assuming that we are affected in a like manner, that we are living through similar events almost simultaneously, this expression also recalls the importance of showing solidarity as soon as our “being together” is put to the test.

“In the Same Boat” is also the title of philosopher Peter Sloterdijk’s 1993 book.1 Dedicated to the concept of hyperpolitics, this essay raises questions about the “art of belonging” in a time when the political situation makes it difficult for groups of people, who often have little in common, to exist as a community. After having succinctly sketched out the two stages that preceded the “wired hyperbubble,” the author draws a portrait of our aversion to those who govern us. He explores our apprehension of the political class within western democracies that are based on a culture of individualism, a culture that compels us to rethink the foundation on which humans do not readily accept any form of authority. From this perspective, he underlines the interest today that many have in “the artist’s life,” representing individuals freed from conventions of the past, and destined to live in new ways of being together. In this context, he believes that it is essential to envisage a hyperpolitical society, consisting of a community that in the future will have to “build on improving the world.” But to accomplish this, it is also necessary to rethink our shared life. One that must thus be lived as though it was a laboratory in which the objective is to lead us collectively towards new solutions.

Although the word “laboratory” nowadays covers a broad range of meanings that sometimes may appear excessive, from a socio-political perspective it is a rather stimulating metaphor for the intellect. It is in these terms that the mayor of Montreal, Valérie Plante, recently described the multiple measures her administration has taken as part of its proposal to experiment with ways of sharing public spaces over the summer in the time of coronavirus. However, the word “laboratory” historically refers to a workspace that is specifically associated with the world of science. It usually designates a place where a restricted group of individuals attempts to carry out research according to rigorous protocol. At a time when scientists quite often donned the white coat of the researcher, these experiments were mainly carried out in the field of natural science, such as physics, chemistry and biology. That being the case, it is no longer a question of considering them as scholars who attempt to carry out their research alone and on the fringes of the research community. Save some exceptions, they work as teams, according to precise plans, if not to experiment or explore new avenues. Consequently, a laboratory is a place where our knowledge is the result of shared efforts. It is a place where individuality often only becomes meaningful in the context of a community. For decades, this notion of the laboratory has spread to many disciplines in the social sciences and humanities, but also to the field of artistic practice.

This “Laboratories” issue explores several avenues that this word suggests in a broader sense. Pamela Bianchi’s text analyses the imaginary world of laboratories and how this is reflected within cultural institutions. After a quick historical overview, she focuses on several contemporary examples, such as the institution formerly known as the Witte de With and the OGR cultural centre in Turin, which both strive to be places of rigorous experimentation. Barbera Tiberi’s contribution takes a look at the creative experimentation that has developed since the 1960s at the intersection of industry and the art world. Because some factory workshops are transformed into laboratories, artists have to adjust to a production context that serves the capitalist economy. But the idea of the laboratory as a collaborative workspace is also an occasion for some groups or artist collectives to initiate interventions that can only take place as a team. Aseman Sabet, who edited this collection of thematic essays, presents Forensic Architecture, a research group based in London that shares knowledge and skills in order to carry out investigations for humanitarian and legal ends. Remaining in the category of interdisciplinary association in which the principle of the laboratory is considered to be a vector of change, Sabet interviewed Erin Manning, the founder of SenseLab, a polymorphous laboratory housed at Concordia University, which combines philosophy, art and activism.

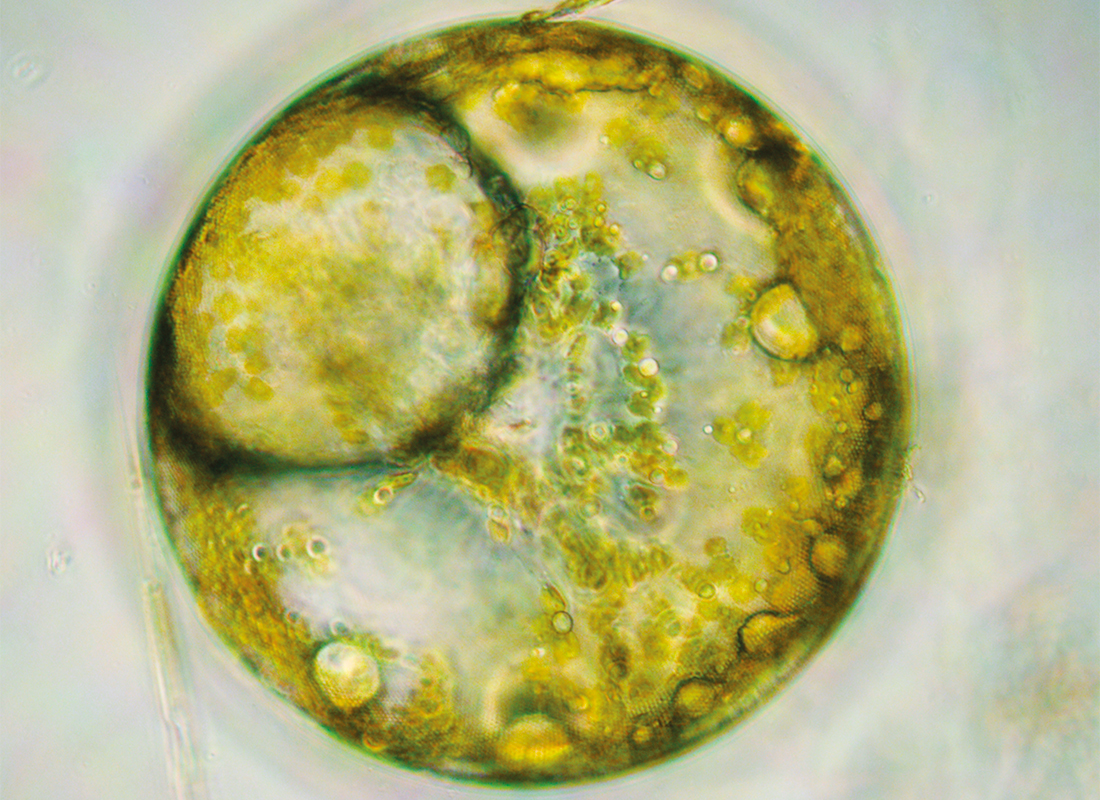

From a perspective more directly linked to the scientific laboratory, there are several artists whose practices are tied to subjects and methods of scientific research. In this light, Marie Siguier focuses her attention on certain works of artist Hicham Berrada. Through his collaborations with several researchers, the artist/lab technician aspires to a vision of art in which nature becomes his main asset. For her part, Kyveli Mavrokordopoulou presents the practice of four artists, Eve Andrée Laramée, Susanne M. Winterling and the duo Marjolijn Dijkman and Toril Johannessen—all of whose interest in science research is nevertheless tempered by a healthy critical distance as soon as it is associated with political power. This also applies to artist Laurent Lamarche, who spoke to Marie-Ève Charron about his fascination with what scientific research proposes in terms of knowledge of reality, while expressing calm scepticism of such research as soon as it seems to become the only source of truth.

It is true that the imaginaries of science and artistic creation generally don’t follow along the same lines. In his essay, Matthew MacKisack discusses the role of the imagination in science, taking experiments in cognitive science as a point of departure. Finally, to come back to the idea of the laboratory as a space for discussion from which new ways of improving our shared existence can emerge, Simone Chevalot interviewed Massimo Guerrera and Sylvie Cotton on the subject of their performance project titled Domus (Les résonances des plateformes). This laboratory-work, being spread out over a period of ten years (2017-2027), is based on an “aesthetics of union” capable of stimulating an art of belonging that invites us to imagine the future of the community beyond the isolation of solipsist thought.

To complete this issue, the “Event” section proposes Marjolaine Arpin’s text on Némo, Biennial of digital arts. She focuses on the main exhibition shown at CENTQUATRE-PARIS, and the theme which is about an end to our world when the future has come to pass. The “Reviews” section follows with eleven texts on recent exhibitions, many of which were interrupted due to the pandemic.

Translated by Bernard Schütze

1. Peter Sloterdijk, Im selben Boot – Versuch über die Hyperpolitik, Frankfurt am Main Suhrkamp, 1995. (not translated into English).