Dictatorships in the neoliberal age

It is remarkable that the idea of dictatorship

is as contagious today as liberty was in bygone days.

Paul Valéry1

The idea of dictatorship straightaway evokes a political regime in which the authority mostly rests in the hands of a single person. In just two centuries, this mode of power has risen in parallel to democratic regimes, which are based on—at least in principle—the state’s guarantee of fundamental freedoms. But one must also bear in mind that this notion of dictatorship is not limited to a single authoritarian vision. In seeking to overcome the injustice that class privilege causes, Karl Marx envisaged the dictatorship of the proletariat as a necessary passage in order to achieve a more just and equitable world. Nowadays, faced with the urgency to radically stop global warming, others are wondering if we should not impose an ecologism in order to remedy the inaction of democratic regimes, which have failed to accelerate the process to the detriment of our freedom as consumers. In other words, as a form of governance, dictatorship responds to various ideologies that demand either order or equity. Yet, in a more subtle manner, can it not also be exerted from within a democratic system?

On the eve of World War II, the rise of dictatorships in a Europe that had fought so hard for freedom puzzled the poet and philosopher Paul Valéry. This thriving growth appears to be with us still and is currently taking on various forms. Of course, populism is rapidly gaining ground, but can dictatorship also develop in our consumerist societies in which certain values are upheld, notably, by way of advertising or “the art of living.” In this regard, paragons of beauty and lifestyles are proposed on the basis of images transmitted by the media. This dictatorship of beauty, success and performance at any cost is often reflected in the promotion of consumer goods. As Dominique Bourg explains, for decades neoliberalism has been imposing its economic power above and beyond our political sovereignty.2 As a decision-making body, politics renounces its sovereignty in favour of economic, or even technological entities, which direct not only the ways we act, but also how we think. Therefore, the dictatorship is not necessarily linked to a regime that is controlled by a single tyrant. Quite the contrary, its tyranny is manifest in a subtle manner on various social media and advertising platforms, which shape our behaviour, for example through algorithms that recommend products or activities. Discretely, these social phenomena, based on another’s hold over oneself, compel us to what Alain Accardo calls an “involuntary servitude.”3 In view of these market diktats to which we have consented, often blindly, certain critical discourses that artists put forth are quite revealing.

For the book, titled La dimension éthérique du réseau,4 the artist photographer Benoit Aquin took pictures on several continents and countries of all political allegiances to highlight what he calls the “the dictatorship of efficiency.” The book shows cityscapes filled with mobile telecommunication relay-antennas and electrical grids, but also people glued to their smartphones. In a text that he addresses to a certain Elena, Anton Bequii, the author’s imaginary alter ego, speaks of his worries regarding technological abuses. He takes stock of the horrible context in which humanity is carrying on and questions the power of art and its capacity to impart something of worth in these circumstances. Nevertheless, while for some this deadly logic heralds dark days, for others the multiplication of telecommunication networks makes it possible to envisage a better relationship to our immediate surroundings. But, it must be said, this hyper-connected world is also the new norm wished for by the “happiness industry.” Our Happy Life, an exhibition presented at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in the autumn of 2019, sought among other things to highlight the way in which new technologies impact our quality of life. For the curator Francesco Garutti, who was interviewed by Aseman Sabet, this way of quantifying happiness within “emotional capitalism” is in symbiosis with a neoliberal economy for which well-being is dictated by our submission to a programmed life. For his part, in order to outwit this authoritarian neoliberalism, the artist Julien Prévieux reappropriates tools produced by the quantification system. In an interview he granted us, he explains that his work dissects the principles of measurement, evaluation and surveillance of individuals and thus “opens up a research field that critiques the current models of the society of control.”

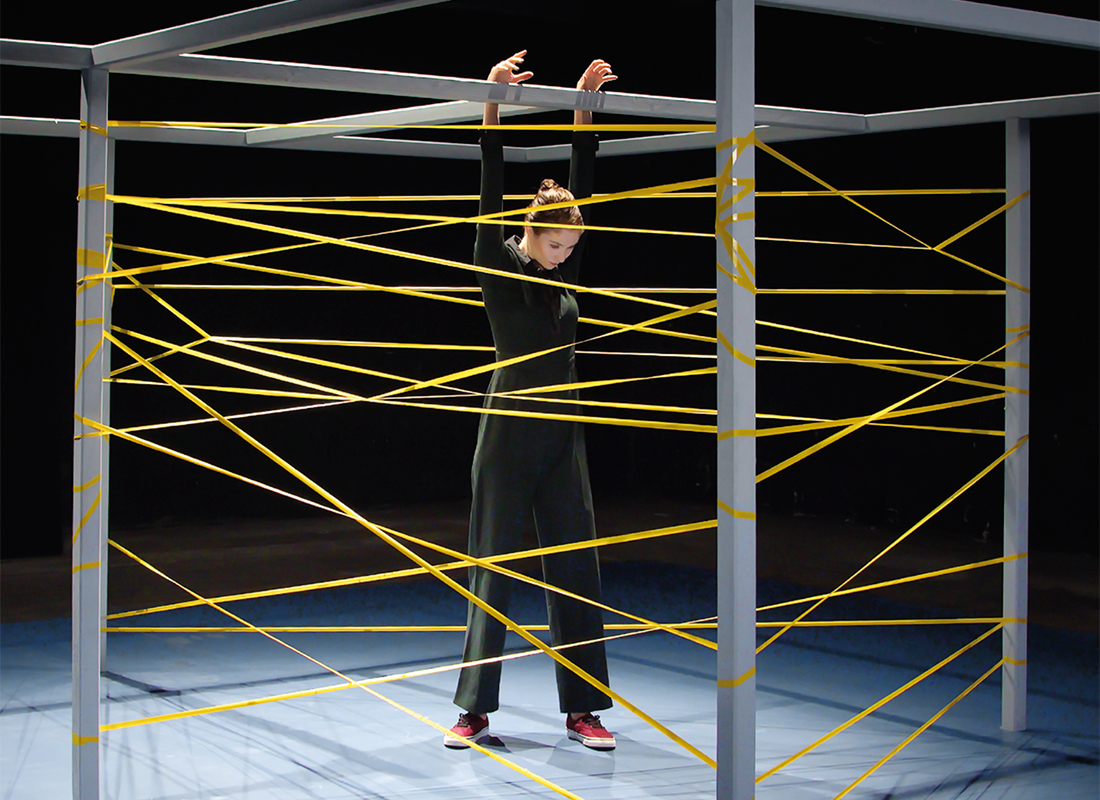

In the sphere of representation in which art is exhibited, the latter can act as a counter-power. The Chilean artist Voluspa Jarpa, some of whose interventions Diogo Rodrigues de Barros analyzes, seeks to remind the Chilean people of the importance of not forgetting the sufferings they were subjected to under the regime of Augusto Pinochet. In thus intersecting art and politics, Jarpa invites Chileans to reflect on their responsibility as citizens. This relationship between art and politics is also imperative when it comes to resisting governmental decisions that are increasingly being taken to the detriment of artistic freedom. This is what Juliette Soulez briefly evokes in reference to certain Eastern European artists, notably in Poland and Hungary, who oppose the political authorities’ efforts to muzzle cultural institutions and critical discourse. The aim of this opposition is to maintain free discussion spaces in order to stimulate debate about social issues that public powers flout. It is also in reference to the phenomena of post democracy that Cristina Moraru analyzes various artistic propositions that she considers to be non-consensual zones, spaces that provide another way of looking at social life. This tension between art and politics is also a focus point in Umut Ungan’s text, which draws inspiration primarily from Oliver Marchart’s notion of conflictual aesthetics; according to the author, in order to be critical, art must occupy the social sphere of struggle whereby artists and citizens meet. This linking also appears to be essential when art is no longer considered a product, but rather as a way of approaching life in a context where it is no longer presented as an exchange value, but rather as a use value. This is something that was already favoured by Gustav Metzger in the 1970s through his advocacy for an art strike and the call to turn one’s back to the art world production system, as Ariane Daoust and Aline Ginda recall in their text on the dictatorship of growth.

To complete the subject of this issue, in the “Debate” section, Samir Gandesha highlights another form of dictatorship, this time associated with morality, that a certain faction of leftist identity politics seeks to exert when it imposes its vision on what is morally permitted or not, and this without invitation or dialogue. In this section, which we are inaugurating with the current issue, we would like to provide a place for reflection about artistic expressions that may prompt a polemical discussion. Finally, the “Events” section presents the texts of Joni Low and Alexia Pinto Ferretti, both on the practices of Indigenous artists. This is followed by the “Reviews” section in which eleven texts focus on recent exhibitions, as well as the section dedicated to recent publications.

Translated by Bernard Schütze

1. Paul Valéry, “Au sujet de la dictature”, in Regards sur le monde actuel et autres essais, Œuvres, tome II, Paris, Gallimard, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 1960, p. 981. Translation mine.

2. Dominique Bourg, Le marché contre l’humanité, Paris, PUF, 2019.

3. Alain Accardo, De notre servitude involontaire, Paris, Agone, 2013. Translation mine.

4. Benoit Aquin, La dimension éthérique du réseau par Anton Bequii, Arles, Éditions Photosynthèses, 2019.